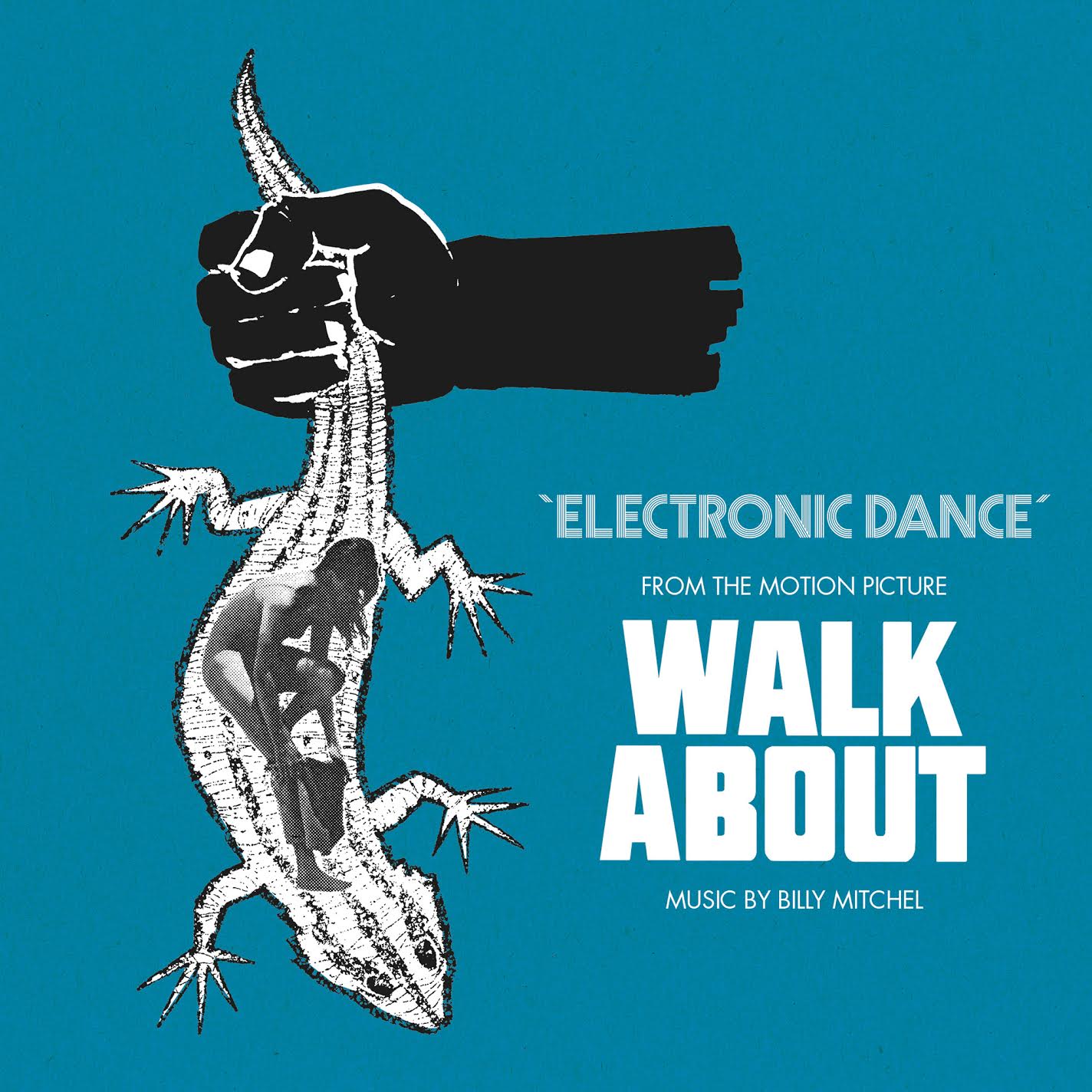

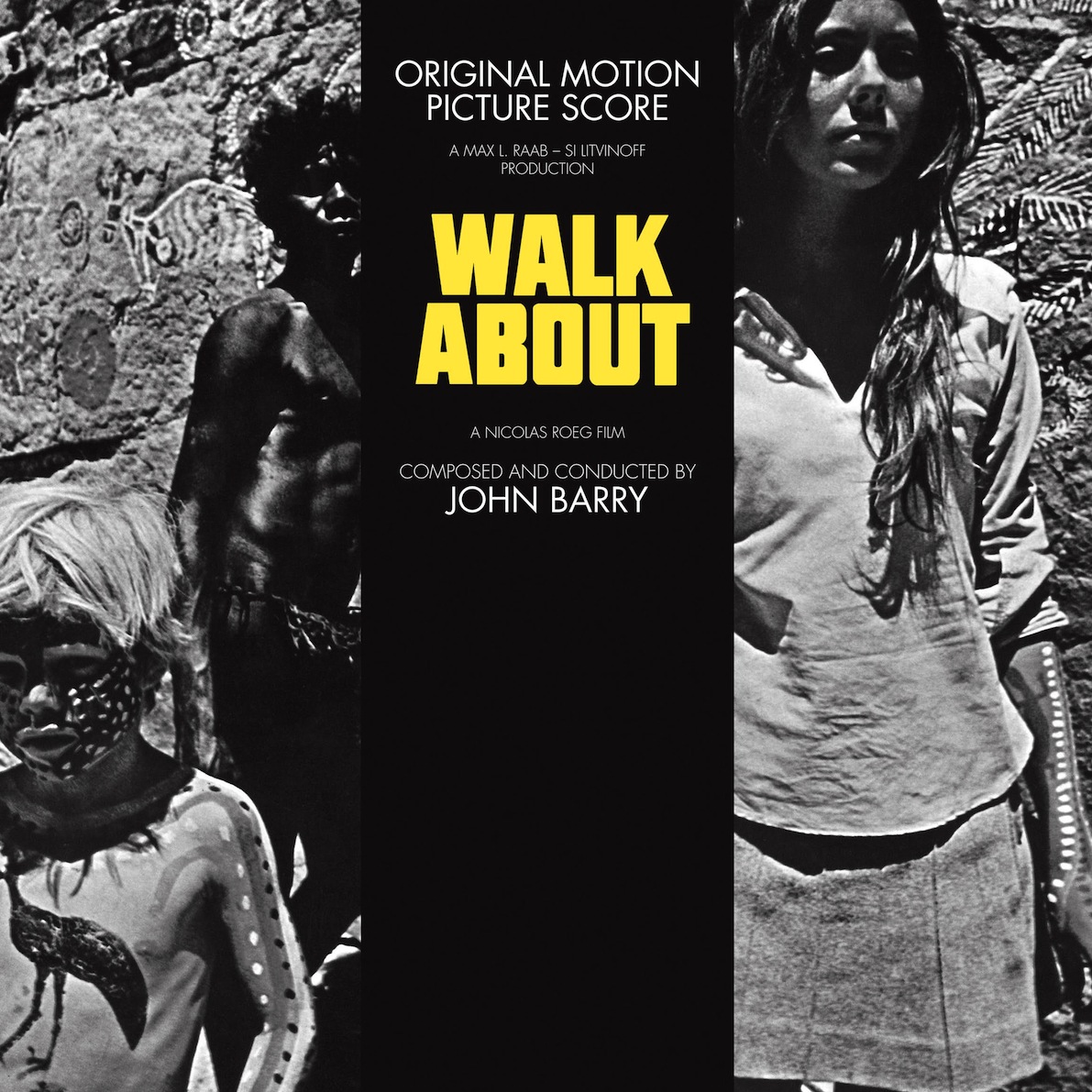

The scene opens with the outlandish twang of a didgeridoo. Of course it does. Then the kaleidoscope turns. The thrum of a harpsichord and a lush, romantic weave of strings and woodwinds conjures a very particular timbre of nostalgia: Midnight Cowboy dreaming of The Ipcress File.

It’s the main theme to Walkabout, the cult Aussie cinema classic — lost since the day it was shelved, on the eve of release, 45 years ago. To hear the needle crackle at last in its groove is weirdly, wonderfully intoxicating.

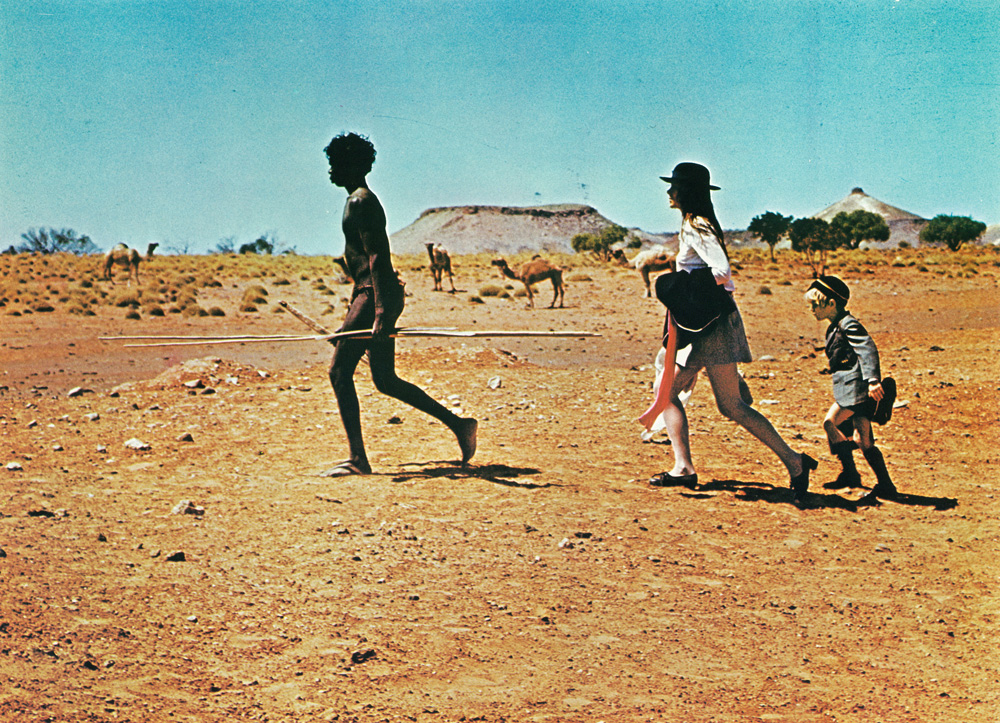

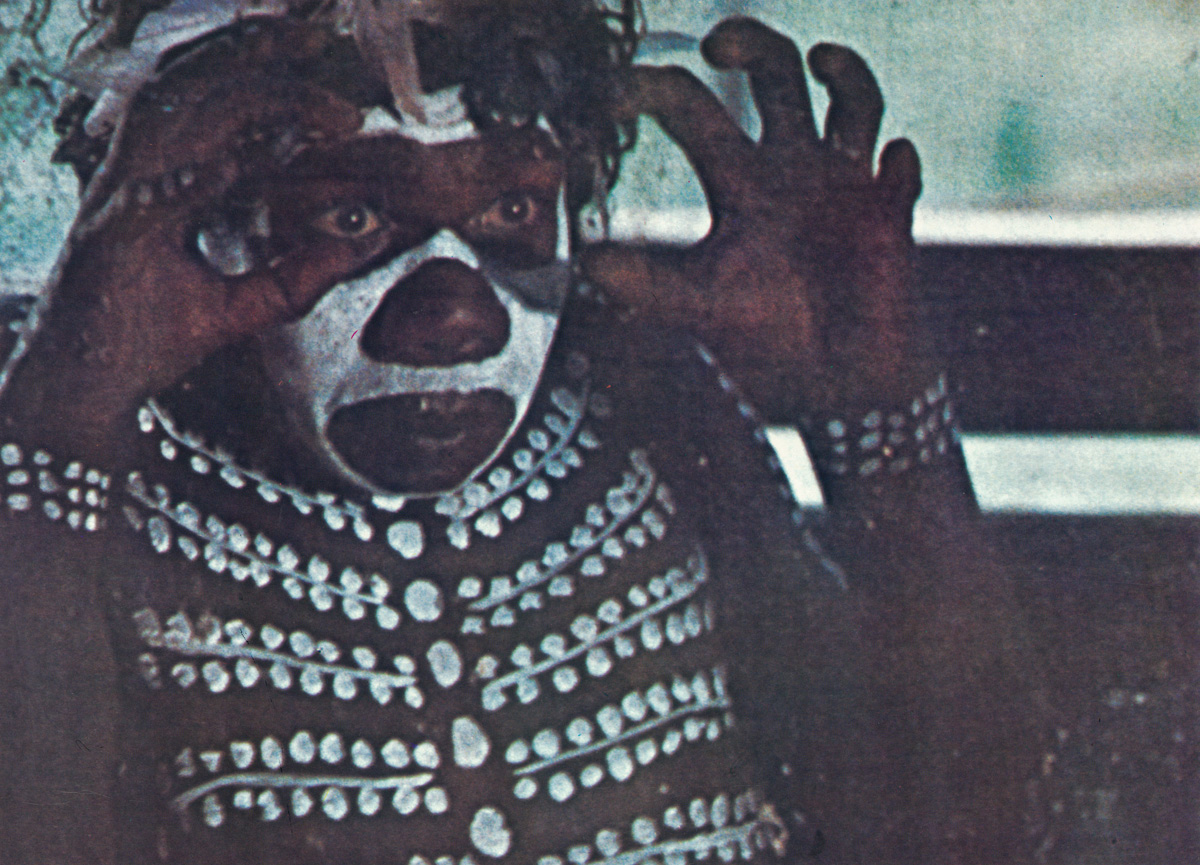

Composed by the great John Barry with all his Bond-film swoon and simmer but cut with hippie sitars, spooky choral segues and primitive electro, the full 33-minute soundtrack is as surreal as director Nic Roeg’s British lens on the alien Australian desert.

“This was the holy grail,” says indie label owner James Pianta, as he flips the 12-inch vinyl sleeve with the catalogue number PM001LP. “It’s an iconic Australian film. John Barry is a legend. The music was lost — and it needed to be found. Someone should have done this years ago.”

‘PM’, by the way, is for ‘Preservation Material’. This record is the latest treasure in an ongoing cultural detective story worthy of Indiana Jones — if only the good Doctor cared as much for obscure Australian film music as biblical relics.

The soundtrack to Walkabout took five years to find, in a warehouse in New Jersey, where it had gathered dust since 1972. Though revered today, the strange, poetic, confronting film starring the young David Gulpilil was not the hit its US investors hoped for. John Barry’s Grammy win for Midnight Cowboy two years earlier couldn’t guarantee a release for his Walkabout score.

“People have been trying to put it out for decades,” Pianta says. “A bootleg came out in the ’70s which was out of pitch and missing tracks. I think it was from John Barry’s personal tape. Classic fan job.”

The Prague Philharmonic addressed demand with a complete re-recording of the score about ten years ago. Close, but no cigar, says the slight grimace on the Australian music detective’s face.

“I like to think we approach things differently to some of the bigger labels. They obviously didn’t go to the effort that we did because in the end it was quite simple, really, to find the tapes. You’ve just got to think differently.”

After years of dead-ends, from Roeg’s own faded recollections to disinterested film companies, it was producer Phil Ramone’s personal quarter-inch dub that was unearthed in Jersey. His son, Simon Ramone, licensed it for an upfront fee, as well as the standard royalty.

“I don’t usually do that,” Pianta says. “But this is Walkabout.”

Physical location aside, the actual ownership of forgotten intellectual property is the major obstacle to bringing such treasures to light, he explains. He itemises the various parties in this investigation with forensic detail: the Hollywood producers Max Raab and Si Litvanoff; the songwriter living on a commune in Woodstock; the estate of Karlheinz Stockhausen that he chose, in the end, not to mess with.

“You speak to whoever you can. You get a bit of inspiration and maybe a new lead to a new trail that will take six months to follow to a dead end. Then you have to start again.”

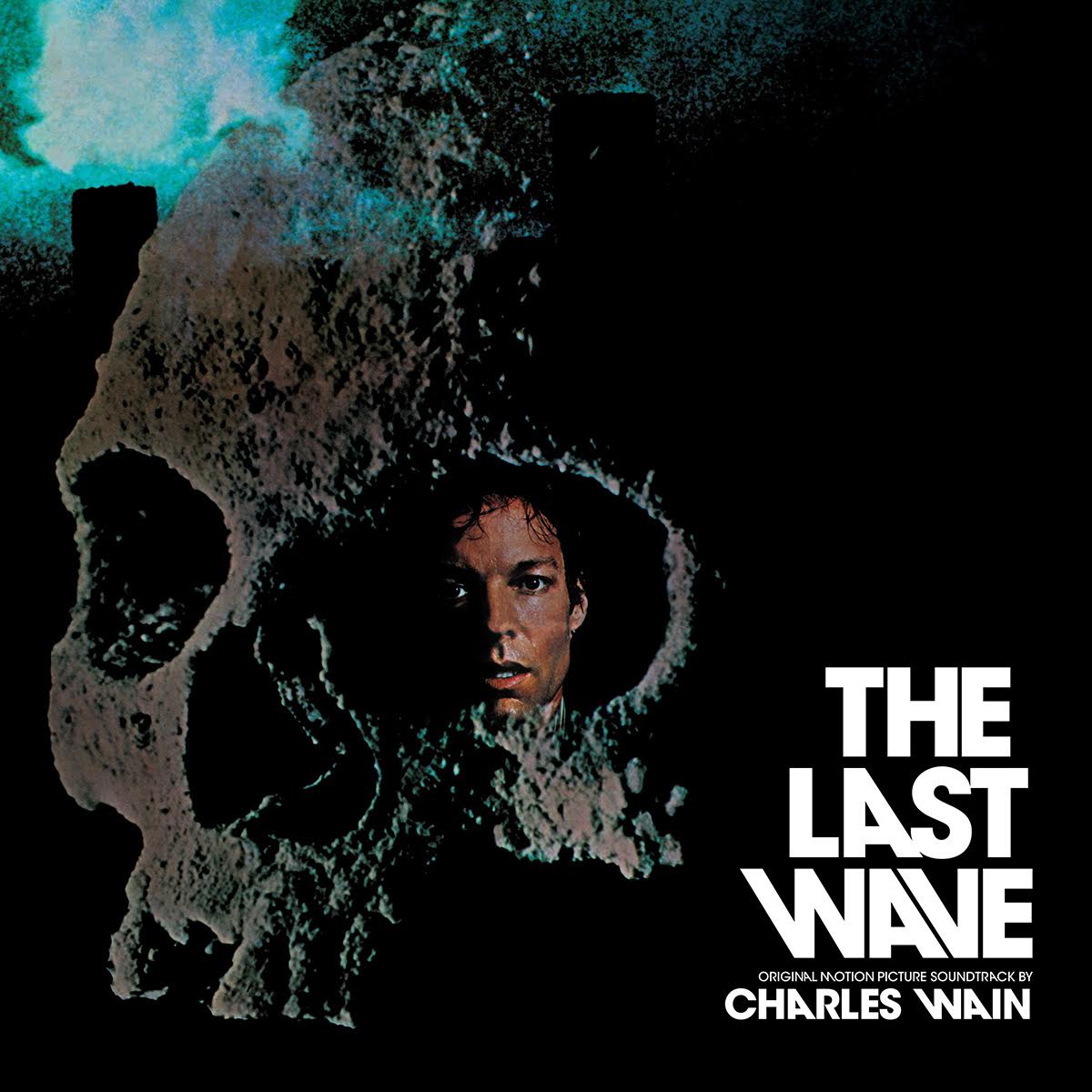

He smiles and leans into another story about another recent preservation project. The search for the soundtrack to Peter Weir’s 1977 mystery The Last Wave led him into the final days of the extraordinary life of one Charles Wain, aka Groove Myers.

“He was in a lot of beat bands in Sydney in the ’60s, then he started working in advertising. You know that CCs ad, ‘You can’t say no’? Or those KFC ads with Hugo and Holly?

“Turns out he was quite a subversive character. He put all this subliminal anti-meat industry stuff into those ads.” Pianta chuckles. “He had this bohemian pad in Sydney and he was a father figure to a lot of young bands that used to come and record…”

Groove Myers died last year, in a Sydney nursing home, not long after Pianta tracked him down.

The Last Wave and Walkabout are among nearly 50 releases on the Roundtable website: mainly obscure jazz and soundtrack material issued with various partners over numerous labels since Pianta’s first project: the lost score to Ron and Valerie Taylor’s underwater TV series of the mid ’70s, Inner Space.

“It’s just the kinda music I like,” he shrugs. “Someone’s got to preserve it. This stuff has to be honoured and shared otherwise it’s going to be meaningless.”

The grim prediction is too feasible. The only known negative to Wake In Fright, another Australian classic from 1971, was famously rescued from a shipping container in Pittsburgh in 2004, its contents labelled ‘For Destruction’.

As it happens, “I met with the composer of Wake In Fright, John Scott, in London last year,” Pianta says. He looks out the café window. “That one might take some time.”

James Pianta’s website can be found here. Walkabout is currently screening on ABC iView