In March 2017 Venezuela’s highest court, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, stripped the National Assembly of its authority. This signified the rupture of the country’s democracy and its constitutional rules, denying Venezuelan people their right to elect government representatives. In April President Nicolás Maduro sought to stifle dissent by deploying the military to the streets, but opposition protests still took place on a massive scale. In Venezuela there is no democracy, there is political persecution and human rights are being violated on a daily basis.

Venezuela is meanwhile facing its worst economic and humanitarian crisis. Despite having the largest proven oil reserves in the world, it also has the highest inflation, 800% and rising. It is plagued by insecurity, poverty and hunger, and is the second most dangerous nation on earth, with a homicide rate of 91.8 per 100,000 residents, according to OVV (Venezuelan Violence Observatory – 2016).

Medicine and food shortages are +80%

Inflation on food reached 600% (2016)

8/10 Venezuelans live in conditions of poverty

93.3% of Venezuelans don’t have enough money to buy food

9.6 million Venezuelans eat 2 or less times a day

Malnutrition and infant mortality rates are rapidly increasing

85% of medicines are now missing (from painkillers to chemotherapy drugs)

Venezuelans are dying due to shortages of medicines and medical supplies

Source: Encovi (Survey on Living Conditions in Venezuela)

I had been interviewing Nadia Hernandez, close friend and prolific Venezuelan Australian artist, about her artistic practice and the humanitarian crisis facing Venezuela. Nadia had recently returned from visiting Venezuela for the first time in eight years. The idea was to explore her childhood memories in Mérida, a valley town high up in the Andes – and then to produce a narrative-based interview that documented Venezuela now.

I was interested in ideas of home and hope amidst destruction and how art could be used to facilitate change. Nadia and I conducted three interviews over two months in various locations throughout Sydney: Gunther’s Dining Room, Prince Alfred Park and at her studio in St Peters.

She began by telling me the things only she could. We spoke about her second birthday party in Mérida and the kid who blew out her birthday candle. We spoke about her return to Venezuela, her grandparents, how she familiarised herself with their faces, and the wrinkles on their hands.

Nadia told me about her country, driving out of the city, the flowers and cacti in the mountains. She told me how little food there was, how there wasn’t any medicine, how the government refuses to admit there’s a humanitarian crisis and how people are dying.

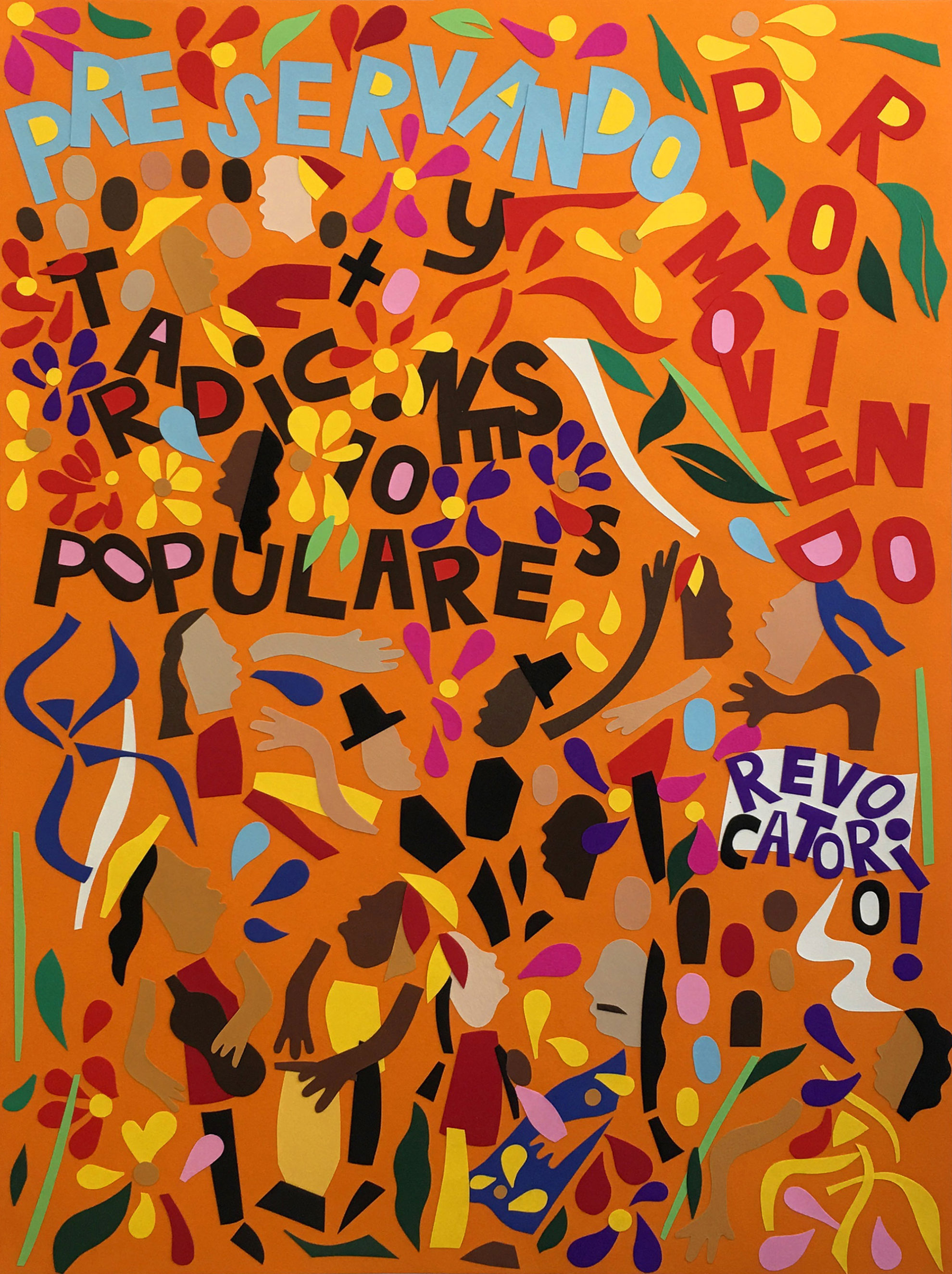

At her studio she told me about her new work. “It’s darker than my previous work,” she said, “but it has to be. I love my country, which is why this is all so sad.” She told me about a piece she’d completed where a soldier eats a civilian. “But,” she said, “the soldier is also pointing a gun at itself too. It references Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son. It’s about authority losing its mind.”

Sometimes the work we set out to do fails. I transcribed the interviews and wrote the story. When I showed Nadia a week later she couldn’t go through with its publication. It was 10pm and due the next day. She apologised but said it was wrong. “It’s too dramatic,” she said. “And the situation is dramatic but the way you’ve written it feels sensationalist. I don’t know. I think this is something I have to write myself. It’s pretty much the most important thing in my life.”

That night I couldn’t sleep. I felt angry, disappointed in myself. I realised I’d done the very thing I promised I wouldn’t: that in the process of attempting to capture Nadia’s voice I’d lost sight of the interview’s initial intent and had appropriated her life as if it were fiction; that as an outsider, as someone who wasn’t from Venezuela, who didn’t understand its culture, its customs, its history, I’d told her story as if it were my own.

But Nadia thought we could save the interview. She thought if we published an article on our history, our friendship and why the interview failed we might be able to learn something about the world and ourselves too. So we imagined the article was no longer an article, but instead a springboard, then a magnifying glass; we imagined people holding the article in their hands and using it to intensify the thousands of questions they didn’t know they had.

“With hands stretched outward into the natural abyss that cradles us, a man in uniform experiences complete hopelessness. You might notice that his hand points a gun toward his helmet, while the other devours another like him. He might be shedding a tear, vultures could be dancing in the distance, a hand appears on the left corner and rummages for food wherever it may find it. You can see mountain icons of the region like the Espeletia and the Cordillera Andina.”

Nadia and I met 11 years ago on the 390 bus travelling north out of Brisbane. I had grown up in Texas and she had grown up in Arizona after Venezuela and we spoke about what it meant to grow up between cultures, what it was to live in a country that didn’t feel entirely like home.

Sometimes she would come over to my place and show me the latest reggaeton tracks coming out of Latin America. “You gotta dance like this,” she would say, shaking her shoulders, her hips, and then I’d be dancing too, horrifically, incorrectly, but: dancing. In the evenings at her house we would make arepas while watching SBS with her mum. I would come over after basketball and Nadia’s mum would tell me I smelled and I would smile because it meant I was finally going through puberty.

I remember Nadia’s poetry readings; walking around the city, South Bank, West End, she would read the things she had written and show me the drawings in her notebooks, the characters she had created. It was 2005. Summer. We were working in a gelato shop and we were graduating. My grades were average and I didn’t know what to do. But Nadia was doing the things other people only spoke about. She was using art to question the world and she made me think I might be able to do that too.

After we’d moved to Sydney, after the characters in her notebook had become more than characters, had developed into their own iconography, after she’d combined folk and popular art with magic realism to navigate and narrate Venezuela, after her first solo show, which proved a resounding success, after rejecting the initial interview for this story that exists only now as an attachment in a Facebook message – although before all that too – Nadia was teaching me how to be an artist.

She was teaching me to never give up, to produce work that finds empathy and searches for hope in a planet filled with violence and pain. She was teaching me the things we should all have learned in school: that instead of pursuing excellence we should value expression and our capacity to question and create and feel.

I listened, then re-listened, to the interviews we’d conducted, to how happy her grandparents were to see her – but how worn out they were by all the things that had broken down: the washing machine, the water filter, the TV, the car, the lamp post that exploded and sounded like gunshots in the night. I listened to her speak about the names of birds, her grandparent’s childhood, the universities they attended, how they sang, sewed, picked then cooked mushrooms, how fortunate they felt to be able to fix the things that no longer worked, unlike other people, who were struggling to put food on the table. I listened to the things Nadia told me – and felt useless because I didn’t know what to do.

The purpose of this article is to remind you that things fail – governments, countries, humans, school, art, hospitals, computers, the UN, corporations, interviews, you.

But within that failure, sometimes, we’re able to birth something new. On the plane returning to Australia, Nadia wrote a poem. She gave it to me and now I’m giving it to you. And while it concludes this story, we hope it births a thousand more:

in my grandparent’s house

you can see two huge mountains

when the fog beings to fall

i feel as though i’m in a natural discotheque

i wait for that mist to descend

and calm the entire city

Mérida is every shade of blue and green

Mérida is the Pico Bolivar

Mérida is La Cara del Indio

Mérida is fresh air

rain through the night

lightning that makes you remember what is truly most high

…Nature

amongst pumpkins and cacao

bachacos and ants

too tired from their incessant work

i find balance and voice

in the dark house

technology fails us

the banana bread gets cold

we laugh at our neighbours

and remembering childhood

those valuable moments that enable us

to fight for a future

whenever it may come