John Derecho hasn’t been home for four months, and it will be the end of this year before he’s briefly reunited with family and friends in the Philippines. The cheeky-faced but quietly spoken 23-year-old is an ordinary seaman, working out a nine-month contract aboard the oil tanker, Stena Paris.

With the ship docked at Port Botany, he’s scored a few hours shore leave on a sunny June afternoon, caught a free minibus to the one place where he knows he’ll be welcome in a foreign city. Here, at the foot of The Rocks, he can buy a SIM card, access free wi-fi, play pool or table tennis. Above all, he can get away from the ship where he works eight hours a day, every day, painting, chipping rust, standing watch.

Derecho is one of about 1.6 million seafarers worldwide. Without them we wouldn’t be driving Hyundais and Mazdas, wearing Uniqlo or H&M clothes, sitting on IKEA sofas watching Samsung and Sony TVs while eating French cheeses, sipping Italian wine, or checking email on iPads.

99 per cent of everything imported into Australia comes on a ship. Australia’s sea exports exceed $200 billion. We expect our clothes not to be produced in sweatshops, and like to feel good about consuming Fair Trade coffee and chocolate. But we rarely think about seafarers, a vital link in the supply chain that sustains our lives and lifestyles.

Seafarers work hard, away from home, for up to a year at time, confined to a clanging, humming world made of steel and primed with grease; risking pirate attacks on the open seas and bullying on board, abandonment in foreign ports with no money to get home. Stress, isolation and fatigue prey upon their mental health.

It’s not necessarily all bad though. John Derecho says his ship is well run and he gets along with everyone on board. But he echoes the refrain of many seafarers. “I’m making internet, Facebook, just to erase my loneliness,” he says. “Then when we are in port like here, we go ashore, just to refresh ourselves.”

Like many tough jobs, money is the main attraction. Derecho earns US$1200 a month, about three times the average Filipino family income. He hopes to start a small business by the time he’s 30. “It’s OK for now,” he says. “I’m young and single.”

The possibilities are perhaps more narrow for Alvin Papel. The 34-year-old sits across the room from his Filipino compatriot, charging his phone. His neat clothes and tidy haircut suggest civil servant more than seafarer. But he’s in port after a two week haul from Mauritius on the container vessel, ER Vancouver. Papel has a wife and two young teenage children. He’s been away for four months and won’t see them before November. As a shipboard electrician, he makes about four times what he could earn at home.

Alvin Papel, seafarer on the MV ER Vancouver. The ship was docked in Sydney and sailing in the evening. Photography by Tom Williams

There’s a gym on the Vancouver, a recreation room, limited internet access when at sea. “We need these things to fight the loneliness,” he says. “The working environment is the hardest thing. Good weather or bad we need to work. Seven days a week.”

In 2015 the ER Vancouver was reportedly attacked by seven knife-wielding men in the Straits of Malacca. In 2016 there were 191 reported piracy and armed robbery attacks on the world’s seas. That’s not the only thing that can go wrong in the wet and wild. Last year, the world’s seventh largest shipping company, Hanjin, collapsed, leaving scores of ships, hundreds of seafarers and US$14 billion of cargo stranded at sea.

Faster turnaround times in port mean getting ashore can be a precious luxury these days. And the only bolthole on dry land for weary sailors such as Derecho and Papel for a few hours on this Sunday afternoon is provided by a charity.

The Mission to Seafarers (MTS) has a rich history, offering succour to seafarers around the world. The Sydney branch provides transportation from Port Botany into the Mission centre on Hickson Road, Millers Point. It’s open 363 days a year, hosting an average of 25 international seafarers a day.

Shipping companies leave it to seafarers to fend for themselves when they go ashore. They provide some support for organisations like MTS but it is dwindling, according to Shane Hobday, a retired Port Authority of NSW executive, and serving MTS board member. “Our contributions from them have dropped from $100,000 ten years ago now to $10,000 a year,” Hobday says.

John Derecho takes a stroll around to the Opera House. Alvin Papel stays around the MTS centre. He doesn’t like to venture out into the city in case he’s tempted to spend money. Both will return to Port Botany and their ships this evening. They will sleep on board, as they do every night of their nine-month stints. The Stena Paris heads back to Singapore in the morning. The ER Vancouver will sail down to Melbourne, around to Adelaide, Fremantle, then to Europe.

Asked to nominate his favourite part of the world, Papel shrugs, smiles apologetically, as if to say he doesn’t have an answer. The message though is clear – while he travels the world, apart from its vast oceans and tranquil harbours, he sees very little of it.

Sydney landlubbers likewise see little of what goes on at Port Botany, the second largest container port in Australia, about 15 kilometers from the CBD. The vast, 276 hectare complex hugs the northern Botany Bay shore.

Only beyond the tight security, high up on the bridge of a ship, can you really begin to take it all in; comprehend the mighty scale of it. Container ships, oil tankers and bulk liquid carriers, row upon row; more than a thousand vessel visits a year. Fields of multicoloured containers – like steely Van Goghs – over two million moving through the port annually. Rust and mustard coloured gantry cranes. From here you can also almost reach out and touch the procession of planes coming in low over the bay to land at Kingsford Smith Airport. It’s the restless epicentre of the ceaseless movement of goods and people in and out of this metropolis.

And it’s a precarious climb up the swaying gangway of the MSC Carolina, a 275-meter long container ship, seven floors above deck and four below. Up on the bridge is the 66-year-old, white-haired, clear-eyed and never married captain, Miljorad Pravilovic. When what goes on out here is closed to the public, and tales of dodgy ships are legion, it’s refreshing to find Captain Pravilovic so welcoming. He has nothing to hide, is happy for us to wander about and chat to the crew. He even puts on lunch.

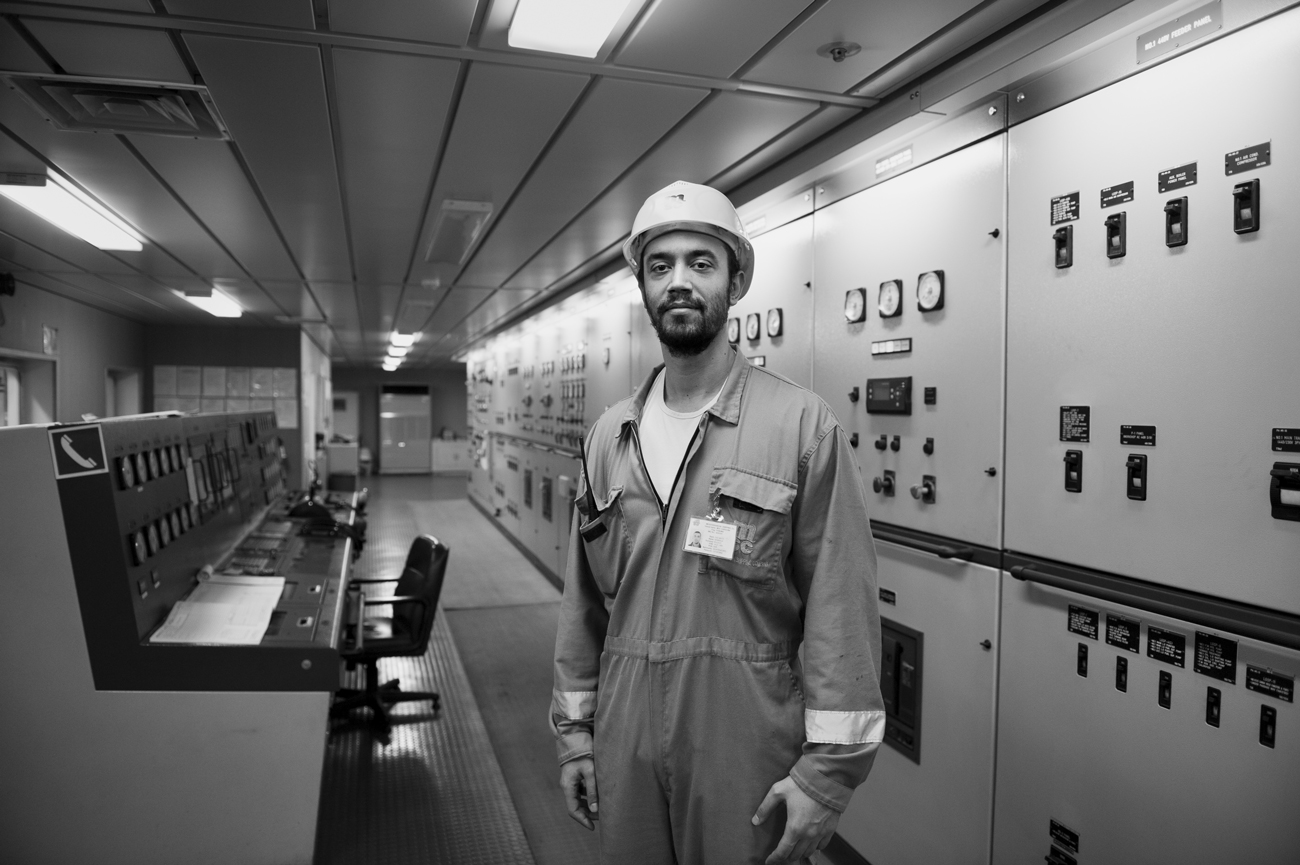

Below deck, the engine control room is impressively high-tech but grey and windowless as a Cold War bunker. There’s a wall calendar featuring an image of a bare-breasted woman. Somehow it doesn’t seem ‘wrong’, just unexpected, but then in keeping with a long seafarer tradition. Only about one to three per cent of seafarers are women and, despite its name, there are none on the Carolina.

Dusko Miljenovic, 34, from Montenegro, sits at a communal table, sips espresso and draws heavily on another cigarette. As a first engineer, an officer, he does better than the lowlier ratings. He’s on a six month contract, bringing in €8,000 a month.

“One hand this is nice job,” he says. “Second hand, very hard job. You are not with family. You are not with friends. This is special calling in life.”

Dusko Miljenovic, first engineer aboard the container ship MSC Carolina, docked at Port Botany, Sydney before sailing in the evening. Photography by Tom Williams

Miljenovic has a baby daughter and another child due in January. He hopes to be home for the birth. It’s a good ship, he says. For now, it marks the boundaries of his world, and those on board are his family. “We have Indonesia, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro,” he says, referring to the mix of crew nationalities. “We live together. We live one life and we are together all time.”

On deck, crew members – Indonesians and one Madagascan – are busy in grey overalls, yellow safety helmets and hi-vis vests, scrambling up ladders, getting the ship ready to sail in less than an hour. Mission to Seafarers’ chaplain, Reverend Un Tay, moves among them, bantering, asking how they are.

Chaplain visits are important for seafarers who can’t go ashore. It might involve anything from helping contact a union about claims of wages underpayment to getting some action to fix an on-board washing machine that hasn’t worked for a month.

The Malaysian-born Reverend Tay speaks six languages, an asset that helps build trust and understanding, the always smiling, effervescent pastor says.

“The need of seafarers comes first,” he says, “not so much trying to preach to them or convert them. Regardless of ethnicity, religion or educational background or rank aboard the vessel we welcome them with open arms. Being human, sometimes they need a pair of ears, someone to listen to the bottled up emotions.”

The mental health of seafarers is a growing concern.

“We can see anxiety levels have increased tremendously, in terms of workload, their salary, family issues,” says Reverend Tay. “And if they face some challenge from officers such as bullying it makes life even more miserable. Often the crew members are reluctant to openly share for fear of being ostracised, or not hired again.”

Reverend Un Tay, born in Malaysia, a chaplain with Mission to Seafarers in Sydney. Photography by Tom WIlliams

One study showed seafarers had the second highest suicide rate amongst all professions. A leading marine insurer recently noted an increase in mental health and suicide-related claims.

Dean Summers is the national co-ordinator of the International Transport Workers Federation, a former seafarer, and now swims the world’s oceans to raise funds for seafarer welfare. “We support an organisation called Hunterlink,” Summers says, “servicing international seafarers in every port in the country, so they have access to highest quality mental health professionals immediately. Last year 1,000 seafarers contacted Hunterlink.”

Shipowners don’t provide seafarers with access to mental health services in Australia. But Shipping Australia Limited, which represents the companies, says it’s a member of the Seafarers Welfare Council which is looking closely at mental health, and will support its initiatives.

There’s been a significant improvement in the quality of ships visiting our ports since the 1992 Ships of Shame Report identified serious problems with some foreign vessels coming to Australia. “Instances of poor shipping and poor treatment of seafarers have dropped off over time,” Dean Summers says. “That doesn’t mean that it won’t happen.”

Earlier this year, an inquest found the deaths of two Filipino crew on the Sage Sagittarius, a ship that visits Australia, resulted from foul play by a person unknown. The NSW deputy coroner noted there was a culture of bullying and harassment on board and the captain had been selling guns to his crew.

The incident drew unwelcome attention to ‘Flag of Convenience’ (FOC) ships – vessels not registered in the country of ownership but in places such as Panama, or even landlocked Mongolia. Many FOC ships are reputable, but the system attracts criticism for facilitating tax avoidance, and sometimes less than scrupulous safety and labour conditions.

And there’s a fierce debate about ships with foreign crews now being allowed to operate Australian coastal routes.

“There are almost no Australian ships working the coast,” says Dean Summers. “Maybe a dozen ships wringing wet… every bit of goods and services we carry around our own coast from one port to another has been hived off to FOC.”

Shipping Australia thinks that’s a good thing and wants the rules relaxed further. The union claims it leaves seafarers vulnerable to exploitation and even poses a national security risk.

The NSW Fair Work Ombudsman is taking action against a Panamanian-flagged oil tanker working our coast, the MT Turmoil, for allegedly underpaying its mostly Indian and Filipino crew by a total of $255,000.

In a submission to a Senate Inquiry, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection said “…there are features of the [FOC] system that organised crime syndicates and terrorist groups may seek to exploit.”

Shipping Australia insists isolated incidents such as the Sage Sagittarius or the Turmoil don’t evidence a systemic problem. It argues allowing foreign vessels to work the coast leads to efficiencies, jobs and less dependence on road transport. Shipping Australia’s spokesperson, Melwyn Noronha, has also worked in maritime security and believes concerns about national security threats tend to be ill-informed or exaggerated. “Yes, we need to be vigilant,” he says. “[But] I haven’t seen any case where the maritime security in ports had to be raised because we had a certain type of ship come in.”

It’s almost 4.30pm and the MSC Carolina is about to sail. A golden twilight glow begins to settle over Port Botany. It is hopeful in its beauty but somehow also invokes a mood of longing and loss. On deck, an Indonesian seaman chats about his life. And then he says, “Do you have anything for me?”

It’s not clear at first what he means.

“One magazine, something like that?”

The irony is inescapable. His ship has the capacity to carry almost 6,000 containers full of stuff. And he’s asking if we have anything for him.

When told ‘sorry, we don’t’, he continues to gaze hopefully for a moment, glances towards the Botany Bay heads. Then he turns away and gets back to work.