In 1969, Opera Australia commissioned one of Australia’s most notable composers, George Dreyfus, to compose an original Australian opera. It was never performed. Almost 50 years on, Dreyfus is still campaigning for justice.

It’s the opening night of Opera Australia’s performance of The Ring Cycle. Outside the Melbourne Arts Centre the weather is typical for the city; blue skies and sunshine sparring with storm clouds and rain.

It’s not all pearls and bowties arriving for the show. Some have chosen comfort-wear, as if preparing for a long-haul flight. Wagner’s 16-hour opera is divided into four parts. Tonight, it’s the prelude: Das Rheingold.

The program states that The Ring Cycle is a story about humanity. Who cannot identify with a story about power, betrayal and relationships, it asks.

The 135-strong orchestra is warming up inside. A trumpet sounds, its notes fading in and out, carried on the wind. A tambourine and other instruments join in. It’s not coming from inside the Arts Centre — George Dreyfus has arrived and he has brought with him an ensemble, an opera of his own.

White and black typed placards nailed to wooden stakes criticize Opera Australia; one reads ‘Justice for The Gilt-Edged Kid’, a reference to the work Opera Australia commissioned from Dreyfus in 1969 but never performed. Almost half a century later, the now 89-year-old Dreyfus is still campaigning for justice.

Dreyfus works the crowd of arriving guests; he has a fistful of flyers and his shirt is wet from the rain. Some patrons are indifferent, brushing off Dreyfus’s approach. Others recognise the Australian icon, “That’s George Dreyfus!” I overhear one say.

“Oh Dad!”, Jonathan Dreyfus, a successful musician and composer in his own right, exclaims, as Dreyfus lowers himself down onto the ground and lies on his back in front of two of the glass doors. Some of the Ring Cycle patrons are forced to go around Dreyfus to enter the theatre via another door.

A ‘falsetto’ is a high pitched male vocal far above the natural range — it is also the pitch of the security staff member who has been trying unsuccessfully to persuade Dreyfus to reconsider his protest. The security guard pleads with Jonathan to try to persuade his father to get up. Jonathan simply shrugs and says, “He’s your problem I’m afraid.”

The music and madness peaks as the ensemble of family and friends — many of them talented musicians — gather around Dreyfus. They are belting out ‘Ballad for a Dead Guerrilla Leader’, a passage from Dreyfus’s opera.

One of Australia’s most renowned composers lying in the rain in front of the Arts Centre. It has the look and feel of the finale of a blood-soaked opera. He’s just missing the dagger buried in his side.

Born in Wuppertal, Germany, in 1928, five years before Hitler came to power, Dreyfus was forced along with his parents to flee Germany in 1939 due to the rise of anti-Semitism and the fear of what a Hitler-led Germany would bring. Escaping before the Holocaust, the family survived while many other family members perished. George and his brother were separated from their parents for six months before being reunited in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda.

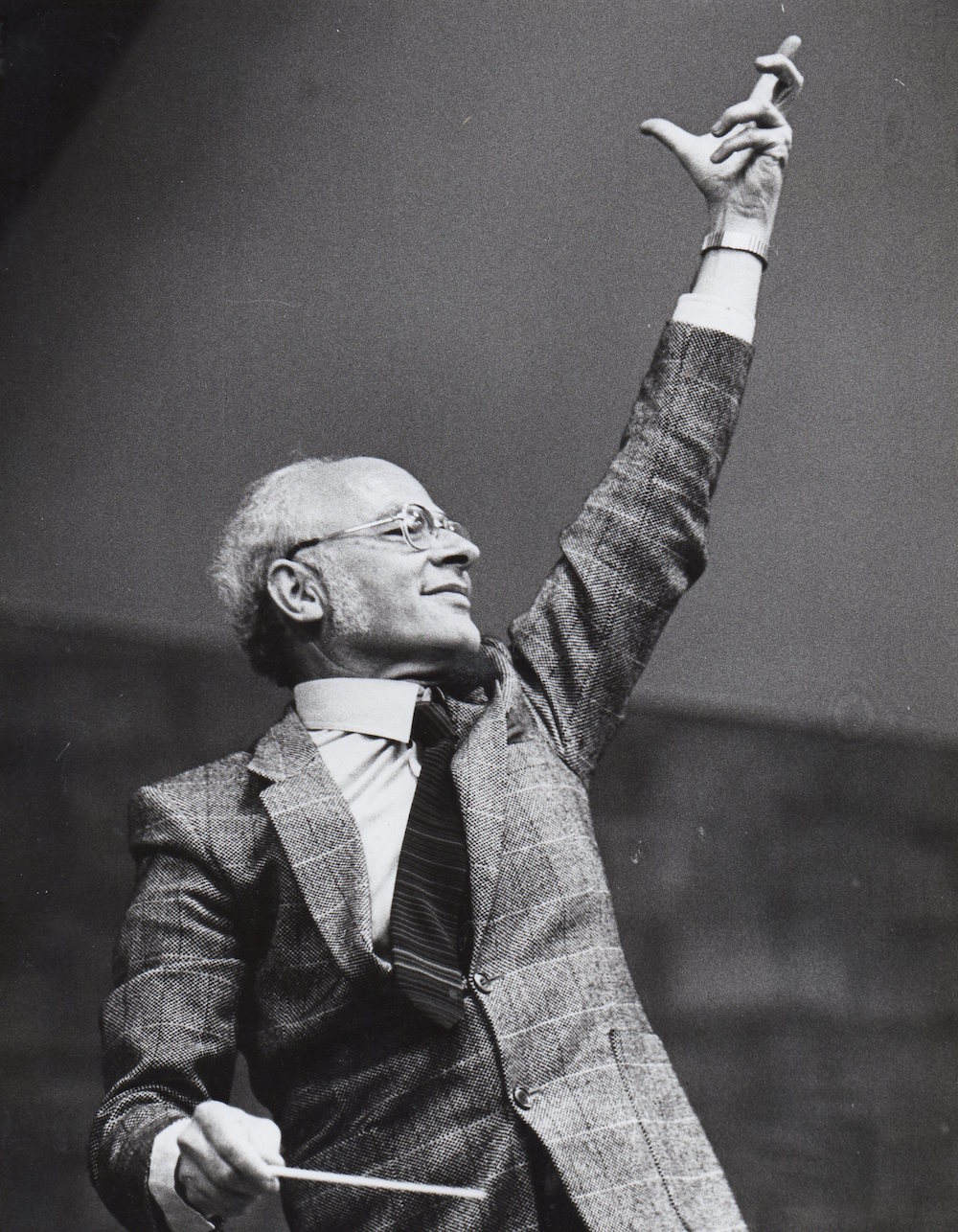

In Melbourne, Dreyfus discovered his love of music at Melbourne High School where he played the bassoon in the high school orchestra and eventually conducted the choir. In 1948, he was a bassoonist in J.C. Williamson’s Italian Opera tour. He went on to be a bassoonist in the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (then the Victorian Symphony Orchestra) for 11 years, from 1953 to 1964.

His career crossed over into film and TV with around 15 television and 35 movie scores. His most famous was the catchy score for the much-loved weekly television show Rush. In 1992, Dreyfus was made Member of the Order of Australia for his service to music. Dreyfus has written four operas that have been performed in Germany, Australia, and the USA. He has also written four books and still plays the bassoon, his “lifelong companion”.

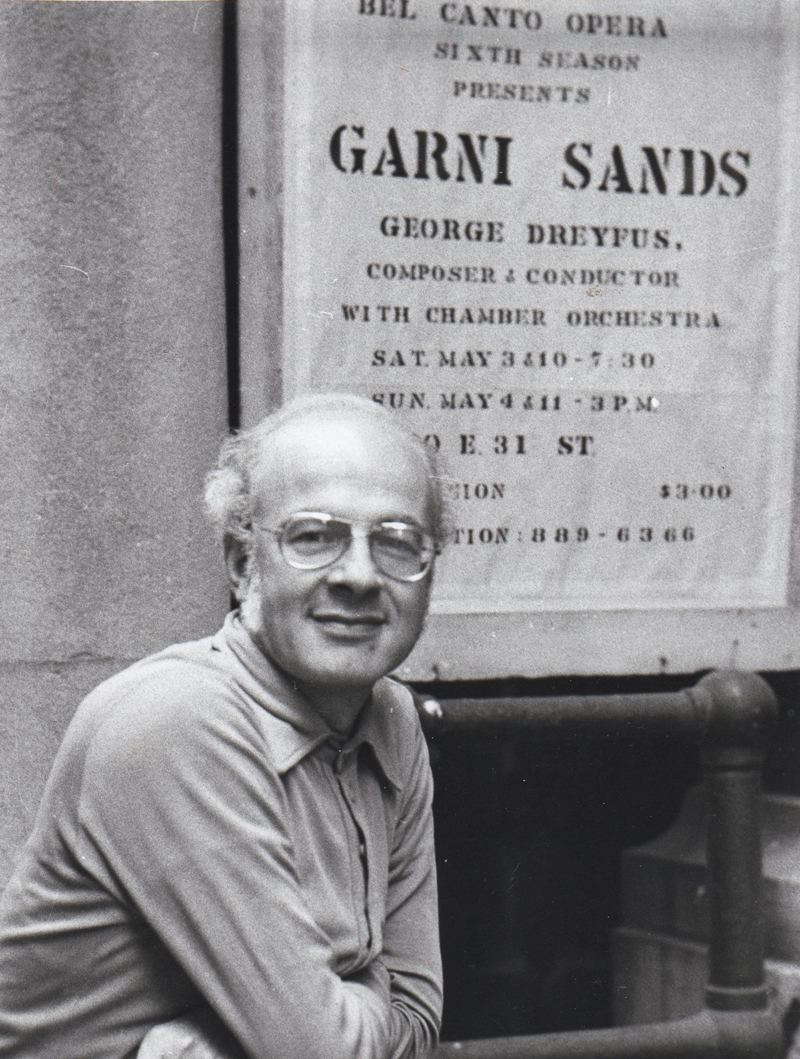

George Dreyfus in New York, 1975.

“Australian music history is very light, because the people in it are very light,” Dreyfus tells me. “It’s only because I stirred, that it ever got into public notice.”

We are sitting in Dreyfus’s lounge room, which doubles as his studio. A writing desk and piano are positioned in front of large bay windows that overlook his garden. A bronze bust of George Dreyfus watches on.

“You might not know, but [for some time] the arts didn’t get money in Australia. Like under Brandis,” he says, in a reference to the former Minister for the Arts, “where all the money is being cut from the arts.”

Things started to pick up in the late 60s, he explains. The Australia Council for the Arts (‘the Australia Council’) had been set up and Herbert Cole ‘Nugget’ Coombs was appointed the founding chairman.

In 1968, Nugget asked Dreyfus to compose an opera based on Coonardoo, a 1929 novel by Katherine Susannah Prichard. Prichard’s novel is a story about race and identity in Australia, focusing on the relationship of a white pastoralist and an Aboriginal woman, set against a backdrop of discrimination, prejudice, and division.

Photography by Sebastian White

If it were produced, Coonardoo would have been Dreyfus’s second opera. Dreyfus recruited Lynne Strahan – author, poet, and short story writer – as librettist to draft a three-act opera and they sent it to Nugget.

But it wasn’t Nugget who responded. Instead, Dreyfus received a call from Claudio ‘Claude’ Alcorso. “He said, ‘I am the new Chairman of Opera Australia I want to come and see you.’”

George invited Claude and his family over for lunch. The lunch would change the course of Dreyfus’s life, setting him on a decades long journey for justice and recognition.

“He said, ‘It is off!’” Dreyfus exclaims dramatically.

“‘Instead of you writing a three-act opera we’re getting five other composers to write one act operas.’” He told Dreyfus that he could be a part of it and create a new shorter opera or ‘just leave it’. Coonardoo, the opera, was discarded and never revisited again.

Dreyfus recalls a feeling of “betrayal”, although he didn’t say it aloud. Instead he decided to accept the new commissioning and signed the new contract.

Lynne Strahan and Dreyfus regrouped and soon had the beginnings of The Gilt-Edged Kid: a political fairy-tale depicting the clash of left- and right-wing ideologues during an Australian leadership contest.

The rebel leader — the Gilt-Edged Kid — wields a belief in human betterment. The incumbent party is ruled by the Administrator, a political moderate who is outmanoeuvred in a series of theatrical leadership games as they struggle for power.

It is Hunger Games meets opera. An archery tournament is the final round and the scores are tied. The Kid hits a bullseye but as he retrieves his arrow the Administrator shoots him dead. It is a slow and furious death. After which, the Administrator is killed by his Chief of Police. The Kid enters the revolutionary ranks of dead heroes. The Administrator is forgotten.

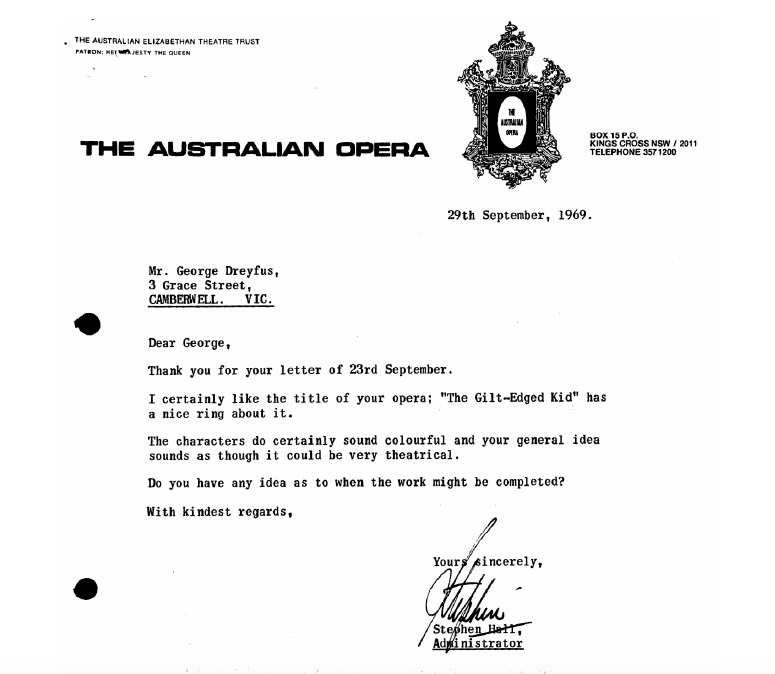

Dreyfus and Strahan received lots of encouragement along the way from Opera Australia — then called ‘Australian Opera’. It’s uncanny that each letter sent from Stephen Hall, Opera Australia’s Artistic Director is also signed ‘Administrator’.

“Do you have any idea as to when the work might be completed?” writes Stephen Hall enthusiastically in September 1969. And then in September 1970, “It is good to know you are in the last stages of The Gilt-Edged Kid.”

It took Dreyfus and Strahan a year to compose the opera. They were pleased — not just with the opera itself, but the presentation too — all the notes were hand-drawn on dyeline transparencies and copied into a manuscript. They wrapped the score in tissue paper, cardboard, and brown paper and sent it off.

It was a shock to Dreyfus and Strahan when they found out via the press that only the ‘best’ opera would be performed. “In the beginning, it was a commission. Gone, it’s now a competition,” Dreyfus says.

Then, on 19 August 1971, Stephen Hall wrote to Dreyfus: “We regret that we do not wish to perform the opera [The Gilt-Edged Kid] at this stage.” Dreyfus felt like the Gilt-Edged Kid himself, shot in the back by the Administrator.

Dreyfus was paid for the commissioned piece, but he recalls that they got paid “less than a street sweeper”. He met with Nugget several times over the years that followed. “But it never led to anything because I had already been wiped off the map.”

In the 1970s newspapers ruled the media landscape, arts reviewers were kingmakers and they were reporting on an opera company in complete disarray.

It was not just the shows that were getting bad reviews — the management and direction were also under sustained attack. The lack of original Australian content and talent was being questioned and it was reported that morale amongst staff and performers at Opera Australia was “at an all-time low”. There was also criticism of the commissioning process that had affected Dreyfus and The Gilt-Edged Kid.

Two of the loudest voices were music critic and composer Felix Werder and theatre critic and librettist Leonard Radic. They were invited as latecomers to enter an opera into the same ‘competition’ for which Dreyfus had submitted The Gild-Edged Kid. Dreyfus claims that Stephen Hall was attempting to buy more favourable publicity by getting the critics on board.

“It’s one in a million works that turns up in a director’s inbox as a completed PDF and suddenly gets put on. It’s a fairy tale,” says Jack Symonds, the Artistic Director of Sydney Chamber Opera. A composer, conductor, and accompanist himself, Symonds believes there is a misconception about the amount of Australian operas that get performed in Australia – and that the number is actually quite high.

“At Sydney Chamber Opera, I would estimate that I get between 20 and 30 completely unsolicited submissions every year.”

At any given moment, he says, there are many artists working on an opera. “The positive thing it produces is a composition culture where opera is revered as the ultimate statement of a composer’s intent for a certain branch of composer. The downside of that is it produces an equally powerful culture of resentment when these composers don’t get their works performed by whom and when they think they should be.

“A commission doesn’t necessarily mean it will be produced. There are many more operas commissioned than there are produced.

“It’s an impossible dilemma. I would say that if a piece is commissioned, and that’s all been paid off, and the deal’s done, then the composer is left quite exposed sometimes. And in a position where they’ve spent years of their life exhaustively pumping out this piece [where] perhaps it might not even reach the stage.”

The full score of The Gilt-Edged Kid is hard to come by. There are only a few complete copies: one is housed in the National Library of Australia, another in the Australian Music Centre library in Sydney, and one in the State Library of Victoria.

Before they were shelved, Dreyfus took a no-frills version of the opera on the road.

“Among the many things I did to keep my opera alive and not let it die by sleight of hand … I reduced the scoring of orchestra to an ensemble of seven players.” The opera was performed in Sydney, Melbourne and Ballarat. There were eight performances in total — the performances were a labour of love. “Nobody ever got paid, but we did it.”

During the 70s, Dreyfus sent letters to Opera Australia and received responses as to why the Opera was “not suitable” or not “worthy” of performance.

The correspondence was full of indignation, which runs both ways. Dreyfus escalates his complaints to the Australia Council and others, protesting the decision. It’s clear that in some missives passion outweighed tact.

As the letters escalate it appears both sides dug in. At one point, Hall wrote to Dreyfus on 21 July 1972, “Your letter has been considered by the Board, and I am directed to inform you that the Company does not intend to give reasons for its decision not to perform your opera The Gilt-Edged Kid.”

The letter went on to say that decisions of this nature “involved difficult matters of assessment” but it did not detail what these difficult matters of assessment were.

“I’m nobody,” Dreyfus says. Then he says it again dramatically. He did not have connections, “friends in high places”, like he thought some of his competitors had.

In recent years, Opera Australia has never been far from controversy. Criticism has ranged from the high cost of tickets, to the lack of Australian content and leads, to the use of government funds on non-opera productions.

Gone are the days of opera companies living hand to mouth. According to their 2016 Annual Report, Opera Australia made $61.8 million in sales revenue and $53.5 million in other revenue of which $25.5 million was government grants. This is a huge amount when you consider that the 28 major performing arts companies had to share in $107.8 million in the same year, an equivalent of about $3.8 million per company.

Opera Australia has come under fire for putting on popular commercial musicals instead of operas. Critics believe that government funds should not be used to prop up blockbuster musicals. There is also the criticism that what is meant to be a national company is highly concentrated in Sydney.

An 18-month National Opera Review was handed down in 2016 which made 118 recommendations to the federal government in relation to Australia’s major opera companies; Opera Australia, State Opera of South Australia, West Australian Opera and Opera Queensland. The review found that Australian Opera companies should present Australia’s distinctiveness in opera. “Australia’s Major Opera Companies should be leading exponents of Australia’s cultural distinctiveness within opera’s artistic traditions.”

The report states that new work “that reflects Australia’s national character and is emblematic of its own time and place is essential to the ongoing artistic vibrancy of the artform.” It recommends that “Governments should support the development of new work, particularly through experimentation, workshops and smaller scale activities.”

It also states that the “track record” of the Major Opera Companies developing new work has been sporadic, recommending that “Governments should create an Innovation Fund which will include discrete competitive funding to encourage the development of new works to which the Major Opera Companies can apply either on their own or in conjunction with smaller companies.”

The National Opera Review recommended that activities funded by the government should be clearly defined and questioned whether commercial musicals should receive government funding in this way.

The government is yet to implement any of the recommendations. However, it seems opera companies have used the review to make some changes. The review has prompted a flurry of Australian productions. What this all means for The Gilt Edged-Kid is unclear. But what is clear is that the winds of change are beginning to blow across the Australian opera landscape.

“It is incomprehensible,” says Dr Thomas Reiner. “Why would you pay all that money to commission someone to write a whole opera which is a significant amount of work and then simply say, ‘Oh, we’re not going to do it.’ I’ve never experienced anything like it.”

Dr Thomas Reiner is a composer, an Associate Professor at the Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music at Monash University and has read the score of The Gilt-Edged Kid. Reiner is a friend of Dreyfus’s, they are part of the same small contemporary art music scene in Melbourne.

Reiner is of the view that if an opera is commissioned then it should be performed. Reiner says that sometimes there are discussions between the commissioning body and the composer along the lines of ‘performability’.

“Someone might write something that is incredibly difficult, or incredibly long, or in any other way unrealistic in terms of performing the piece.” But Reiner says that is not the case with Dreyfus, “because he writes relatively conventional music.”

“The score suggests that there is a substantial and competent work — as one would expect from George. As often with George’s music, the style is rather traditional, but not anachronistic,” Reiner says.

“Would the work appeal to a contemporary audience? Sure, why not; as long as it is carefully staged.”

Mark Dreyfus is the Shadow Attorney-General, and George Dreyfus’s eldest son. He was in his first year of law school when his father was commissioned to write the opera and remembers it well.

“His career was going well… I thought it was a great development that he had been commissioned to write an opera by the Australian Opera.”

But Mark Dreyfus is perplexed that almost 50 years later it still has not been performed. “When you’ve received a commission there has got to be at least some expectation that it’s likely to be performed.”

“As someone who has got standing not just in this country, but in Germany where George has been commissioned to write operas and those operas have been performed…” He pauses, searching for the right words. “It’s a disappointment,” he says with a sigh, “that this opera has yet to be performed in Australia.”

One of the reasons Opera Australia receive so much money is that it is an expensive art form. “I do not begrudge them a cent,” says the former Shadow Arts Minister. “I think it’s great we have a world-class opera company, but it is a fact that it receives a lot of government money, more than all the other opera companies.”

Mark Dreyfus believes there is a tension at the heart of all artistic endeavours and finding the balance is key.

“To what extent are you going to perform works that you know will sell or put audiences there paying and watching and to what extent do you engage in cultural activity that less people might wish to go and see, but will nevertheless be of tremendous interest and enrich Australia’s cultural life? The tension of that decision is one that every arts administrator, every arts ministry has to resolve,” Mark Dreyfus says.

Mark Dreyfus admits to being unashamedly biased when it comes to his father’s work. But it is clear he is not just speaking from the heart. He genuinely admires his father’s work. I ask him if he thinks it will be produced one day.

“Yes, I’ve got no doubt about it,” he says, and adds, “I hope it is performed in my father’s lifetime.”

Brush Off is the name of George Dreyfus’s fourth book. It’s also how he feels he has been treated over the past decades. “I don’t have a future anymore,” he declares. “I’m dead soon, so I can afford to take risks that I would not have taken in the 70s and 80s when I didn’t really do much at all [to protest against Opera Australia’s decision not to perform the opera]. Except yell at a person now and then, of influence, who turned the other way, because Brush Off is about turning the other way. That’s what brush off means.”

“A number of people said ‘George stop’, as in ‘get over it’,” he says. “My aim is not to reform anything. No, I want justice for The Gilt-Edged Kid.”

Dreyfus might not be calling for reform, but it is clearly on the way. Many of the findings by the National Opera Review echo the criticisms that have dogged the opera company since the 1970s. In the intervening years, the company has received more and more funding while the medium seems to have become less and less popular. It is difficult to see Opera Australia changing its mind anytime soon — but perhaps a future Opera Australia will reconsider performing Dreyfus’s opera.

“Australian music history is not overpopulated with issues. It hasn’t got much going. I am filling in a void. I’m doing something which a PhD student, a VCE student could say, ‘Oh I think I might do this unperformed opera.’

“I think human being tradition tells us to fight for what is right.”

“I think it was wrong not to play this opera. And I would like to right the ship before I die.”

Opera Australia was provided with a draft of this story before it was published. They declined to comment.

Photography by Sebastian White

*The Opera company has had several names over the years; Elizabethan Theatre Trust Opera Company, The Australian Opera and most recently Opera Australia. The current name, Opera Australia, was used in this story.