The inner Sydney office of the CEO of Domestic Violence NSW, Moo Baulch, is a place of such light and peace it seems at odds with our meeting’s purpose. Until construction noise breaks the calm. The previous week had been a horror one for domestic violence in NSW. Three women in their 30s killed by their intimate partners (or former partners) in just four days. Stabbing, strangulation and hammer attacks variously ended those three lives, taking the estimated national domestic violence death toll to 38 for the year.

In every case Baulch knows there would have been a long history and pattern of “power, control and psychological stuff”. The protracted lead-ups to such deaths are part of what she calls “the continuum of domestic violence”.

It’s an epidemic that far exceeds our country’s death tolls from terrorism or one punch attacks, she points out. Yet it fails to motivate our crackdown-happy legislators as much. This is despite an Australian Bureau of Statistics personal safety study which shows that one in three Australian women experience physical violence in their lifetime, one in four of them from a partner or ex-partner. On average, one woman a week is killed by a partner or ex-partner.

In the bleak landscape of domestic violence, any mention of the word ‘beautiful’ could seem like a black joke. So I am surprised when Baulch uses it. Her words are slow, steady and perfectly modulated. “There’s certainly unprecedented awareness around domestic and family violence,” she says. “Big corporations are having conversations about it as a workplace issue. The Commonwealth Bank has just worked with us on the issue of financial abuse.

“Five years ago, there was very little interest. But you’ve got this beautiful level of awareness now. You’ve got the impact of Rosie Batty and other advocates speaking out very strongly trying to remove the shame and the stigma of speaking out.”

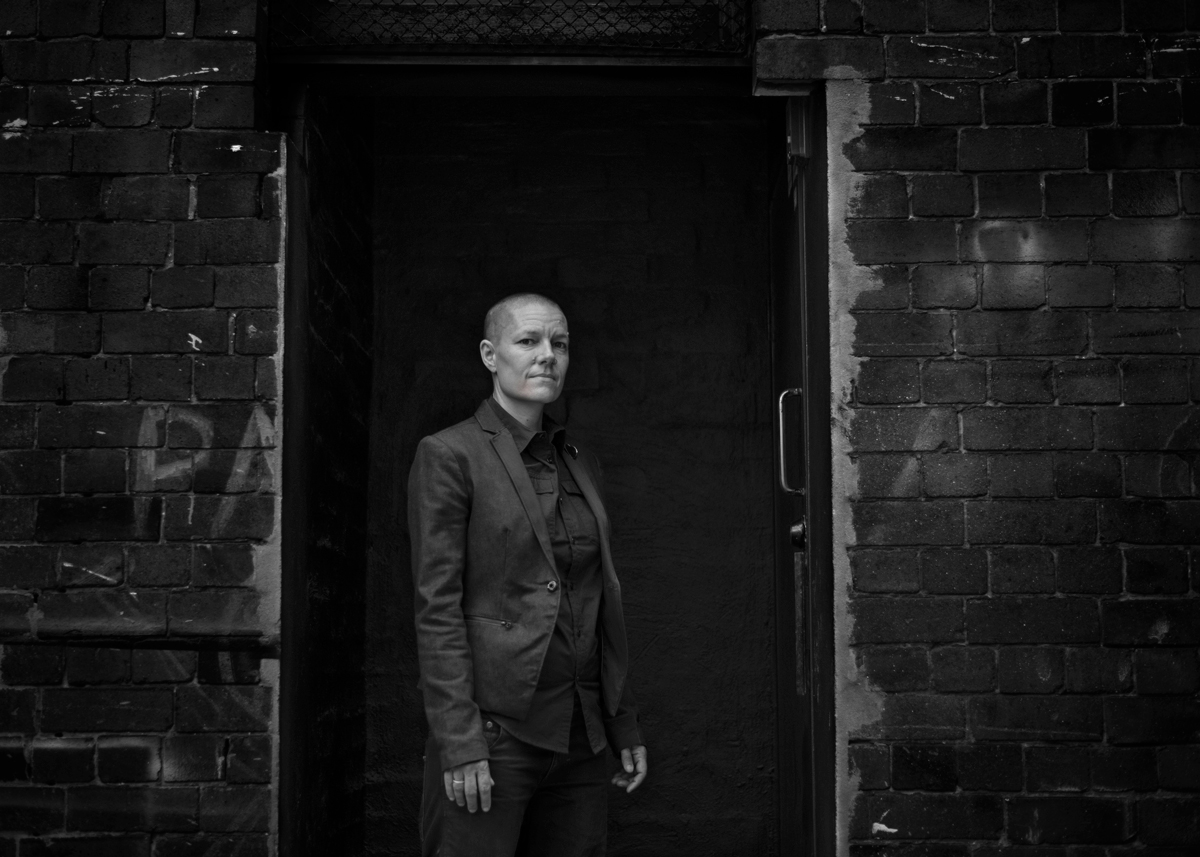

There’s a disarming sense of calm and inner grace to Baulch – the very opposite of violence – manifested in a quiet yet powerful presence, as she fights what can only be described as a world of horror. On each of the three occasions I’ve been in a room with her over the last year this same subtle strength has equalled if not exceeded that of the prominent business and legal figures we’ve been among, and whose respect she has earned.

Baulch came to Domestic Violence NSW after studying in Queensland, having moved there from the UK in her twenties. While doing her Masters degree in peace, reconciliation and historical memory regarding the Stolen Generations, she became involved in addressing domestic violence within the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender, Intersex and Queer (LGBTIQ) community. Because LGBTIQ people are often marginalised already, there is a reluctance to report domestic violence incidents. “One third of gay men and lesbians experience domestic violence and there is a lot of shame associated with it.” Baulch says, “With all the debate and publicity about gay marriage, the last thing we want to talk about is that our relationships may be abusive.”

Perhaps due to her academic background and interest in historical memory, Baulch thinks a lot about turning points. In terms of Australia’s domestic violence consciousness, the 2011 murder of Lisa Harnum was one of them. Harnum’s fiancé threw her off the balcony of an expensive apartment overlooking Sydney’s Hyde Park. “The nation was gripped by this story,” says Baulch. “This woman was bright, she was bubbly, she was beautiful. She was living a fairly affluent lifestyle in an amazing apartment. It was a different story for the media. It wasn’t the stereotype.”

Through the court case, the media showed there was a really long period of control leading up to Harnum’s death. “Domestic violence is not just about homicides, broken bones and bruises. He had been stalking her for a long time. He had been tracking her emails, had installed cameras in her apartment, stopped her from going to work. She went from being this really bubbly person to not being able to wear makeup, having to dress down so that other men didn’t find her attractive.”

Baulch watched the case create a new awareness among the general public. But a cautious optimism is quickly tempered by what she says is “an incredible amount of victim-blaming still. Why doesn’t she leave? There is a perception at the community level that there are places to go, that it’s easy to get into a refuge. If this relationship is as awful as she says it is, why doesn’t she just go?”

The reality, says Baulch, is that leaving is an incredibly difficult thing for a woman to do on a range of practical levels. “We are in the midst of an affordable housing crisis, not just in Sydney but in other parts of the state as well. If you have been in an abusive relationship for some time you may be being financially controlled, you may not have access to your bank accounts or financial resources.”

Baulch is at pains to point out domestic and family violence goes across all socio-demographics. “We’re not just talking about people living on the edge. We are also talking about people who might be living in multi-million dollar houses with five cars. Their partner is controlling all the finances that come in. They’ve been prevented from going to work.”

Photography by Matthew Abbott / Oculi.

It’s just one year but it now seems an age since Malcolm Turnbull’s 2016 COAG National Summit on Reducing Violence Against Women. Baulch will spend the hours after our interview writing a submission to a Senate Inquiry on the 24/7 1800RESPECT trauma specialist service that has more than 100,000 users and for which funding cuts have been announced. The essence of the service’s success to date was that it was staffed by 80 domestic violence-trained professionals capable of tailored frontline responses. Repeat callers – some having up to 50 conversations – got deep and relevant support depending on which crisis stage they were at.

1800RESPECT now seems set to be reduced to a mere information referral function. Baulch’s understated but evident disappointment over the substantial dismantling of something that actually worked is the lot of someone in a role like hers. How frustrating it must be to know the research, to know that certain things make a positive difference and to see them fall prey to economic hardheads and short termism of the sort that costs more money – and lives – in the end.

“The system has failed women, children and men over a series of decades,” says Baulch. “There’s not enough investment in prevention and early intervention and efforts are not coordinated.”

I ask whether Australia fares better or worse than comparable nations in terms of domestic violence. In some ways, Baulch says we are actually leading in terms of individual initiatives like ‘Our Watch’ (an excellent, government funded information and education hub). “But we have a lot of soul searching to do as a nation. We have not only built our country on quite horrific violence, what some would call genocide, the systematic repression of the other. We are still struggling with what gender equality might look like in Australia and for that to be a thing that doesn’t have to threaten men.”

The majority of domestic violence perpetrators, says Baulch, are our sons, fathers and uncles. She says everyone, men included, needs to be part of this conversation and to challenge the attitudes that underpin all violence. “If 17 men were being killed each year [from one punch attacks] in Kings Cross, we’d be declaring martial law, a national emergency. The public will swallow 14 days of detention for a terrorism suspect. But when it comes to domestic violence, we can have three or four murders in a week and our political leaders might not even mention it.”

Expression: “No One Has Ever Seen God” – fast fiction by Margaret Barbalet