On the weekend that ended up being almost the exact midpoint of my hospital admission, I was given leave on Sunday to travel back to Newtown, my home.

I’d been invited, months beforehand, to speak at the Writer’s Tent run by the local bookshop during the Newtown Festival, the annual fundraiser for the local neighbourhood centre, always replete with acrobats, a chai tent, a dog show with a look-alike category. It was a glorious day – that crisp, sharp light of late spring, a hot breeze shaking jacaranda flowers onto the road – and I walked to the festival down Eliza Street, where the inhabitants of a crumbling terrace were playing music and barbecuing vegetarian sausages in their tiny front courtyard, a bubble-blowing machine angled out over the street. The street itself was thronged and milling. A beautiful young woman with a shaved head and black velvet choker pressed a sticker in the shape of a heart onto my chest and I thought, yes, this is my home.

After I spoke, I met a friend in a bar further up King St – furtively, really, as I wasn’t technically supposed to drink – and the man behind the bar started mixing my spirits before I’d even ordered. All afternoon, I felt this small kind of recognition, of solidity – and I felt it sharply because I had been away, was still away, deliberately removed from my regular life and trying so hard to change. I was thin-skinned and uncertain, but my home, my life within it, had remained unprecarious.

When my boyfriend drove me back to hospital, heading into the spilling sun, westwards down Parramatta Road, down the M4, it was all I could do not to cry.

One of the things, I think, that felt most fractured about my time within the hospital was that the landscape around me was so decidedly suburban, so different from the space that I am used to moving through. My window, once I was given a room that had one, overlooked something that may have been a canal, a creek, or a stormwater drain – a thin trickle of water through a steep concrete ditch – and a dry-grassed park backed onto by red-bricked and boxy apartment buildings.

In the last weeks of my admission, I was allowed to leave the grounds to walk here for fifteen minutes each day, and I’d crunch over the dried leaves of casuarinas and bottlebrush seeds. Occasionally, I’d be taken for a longer walk, together with a group of patients, to the Woolworths at the end of this park, where we could buy soap, shampoo, or magazines; the butcher next door was named ‘No-Mis-Steak’, its backlit sign printed in Comic Sans.

The place was beautiful, in its own way, quiet and languorous and filled with bird song, but I missed the press of buildings near my home, the way they cram up close together, overspilling with wetter, fatter foliage – ivy, gardenias, frangipani, magnolia. I missed the press of people, of cyclists, of dogs tangled up outside op shops, clothes shops and cafes. Without them, in this wider, flatter landscape, I felt more soluble, less certain of my material presence, unreflected and alone.

But the strange thing is that this kind of landscape wasn’t new to me; I grew up in south-west Sydney, nestled in amongst precisely this sort of spaciousness and high-fenced privacy, these undemonstrative but honourable lives. It wasn’t that unusual to me, and it is absolutely usual for so much of Sydney’s ever-growing population. I realised this during another brief leave of absence from the hospital – the doctors liked to grant us the occasional evening off, to attend functions or social events, to practice staying safe and sane in our wider, more everyday lives.

I caught the train to Central, past Westmead, Parramatta, Granville, Lidcombe, Clyde. It was just after 5 pm, and the train pulled up each time at stations dotted with people in business suits and backpacks, or polo-shirted uniforms, reading from their mobile phones or tucking high-vis vests into the back pockets of their jeans. At Granville, a towering Islander man sat down beside me, taking up the rest of the three-seat berth, and offered me a handful of his hot chips. Two women in gloriously-coloured print dresses and headwraps held hands and murmured quietly in front.

These weren’t the people I was used to seeing at home – gentrification and de-diversification, after all, go hand-in-hand, and the sprawling suburbs of Sydney’s West are home to almost the same number of people as the rest of the city combined, and more than a third of these people were born overseas, in any one of over a hundred different countries.

I walked through the back streets of Chippendale to a friend’s house, a purple-painted terrace, past two small art galleries, five small bars, dodging the tumble of wheelie bins taking up most of the footpath for collection the next day. This is my home, I thought, but it is not my city.

On the day I left the hospital I left early, so that I could arrive in Annandale, where my boyfriend lives, in time for breakfast.

I ordered coffee, real coffee, sweet-bitter and smooth, the milk swirled into the shape of a heart, the cup a deep, mineral grey. Toasted sourdough, bread that was chewy and seedy, not wet and white. I held my handbag on my lap, because it still felt so novel, so pleasurable to be carrying it around. (Coffee I had known I’d miss; carrying a handbag, far less so.) I drove to Glebe to buy some groceries and bumped into a friend, another writer, walked with her to a park so we could catch up, sitting against the buttressed roots of a fig tree and sipping on take-away tea. I did a load of my own washing, watered the pots of cherry tomatoes growing in my small backyard. I walked along King St, just to feel it on my skin.

I’d missed my home, the habits I have that shape it and are shaped by it, the small pleasures it gives me across the day. And I had missed it all the more because I had been living in that other city, the other part of our city, the shadow-city that makes our own possible and feasible, especially because we rarely see it.

The author outside her home in Newtown.

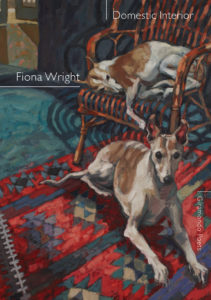

Fiona Wright’s new book of poetry is called Domestic Interior, Giramondo Press, 96pp, $24.00. It follows her award-winning collection of essays from last year, Small Acts of Disappearance.