Here’s a figure to contemplate. The Beatles released their first single, ‘Love Me Do’, on 5 October 1962. The sequencing of Abbey Road was completed on 20 August 1969, a date that marked the last time the four of them would be in a recording studio together. A month later John Lennon declared he was leaving the group, although that news would not reach the public until Paul McCartney announced the group was no more at the beginning of April 1970. That’s less than eight years.

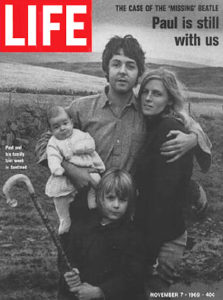

Paul and Linda on the cover of Life magazine, 1969.

Here’s another. Irrespective how you mark their dissolution, it’s now close to half a century since the Beatles broke up. Ringo kicks on, as charming and self-effacing as ever, but in a few weeks it’s 37 years since John was shot on the steps of the Dakota, and sixteen since George Harrison died in Los Angeles. And Paul? Well Paul’s not been a Beatle for five times as long as he was one.

The problem of the afterlives of pop stars isn’t a new one. But Paul McCartney is a special case. Although the reputation of the Beatles has waxed and waned over the decades, few question the scale of their achievement or their centrality to the history of popular music. Likewise critics have come to recognise not just McCartney’s importance as a composer, but his involvement with the world of experimental art and music and his instrumental role in driving the creative growth of the group as a whole.

Indeed McCartney’s output in the almost five decades since the Beatles broke up is often seen as the punchline to a long and unfunny joke. There are stinkers like Wings’ London Town and his dire 1980s solo effort, Pipes of Peace. There are the unspeakable duets with Stevie Wonder and Michael Jackson (I still get PTSD flashbacks from the opening bars of ‘The Girl is Mine’). And the less said about his 1984 movie Give My Regards to Broad Street the better. ‘I like solo Paul more than Wings, and Wings more than the Beatles,’ said no one ever.

Yet my own relationship with McCartney’s work is more complicated. Wings Greatest was the first album I ever owned, a Christmas present from my parents in 1978. Its twelve tracks are imprinted on me in a way few others are. As I grew older I worked my way through Wings’ back catalogue as well as the early solo records. Even then I knew these weren’t the records you were supposed to like. Lennon was cool, McCartney wasn’t; especially if, like me, your other tastes ran to nervy post-punk and Bowie and Dylan.

But I’ve always found McCartney’s music irresistible. I love the playfulness and perfection and even mild daffiness of it, the way albums like Band on the Run, capture the joy at the heart of pop music. And as I’ve grown older that feeling hasn’t faded: the unselfconscious gorgeousness of the best of McCartney’s post-Beatles work always leaves me feeling happier.

It makes me wonder, therefore, if it isn’t possible to tell a rather different story about Paul’s life after the Beatles? A story of creative endurance and often unrecognised inventiveness, and – as his collaborations with Elvis Costello and Youth suggest – of an artist prepared to challenge himself in often productive ways.

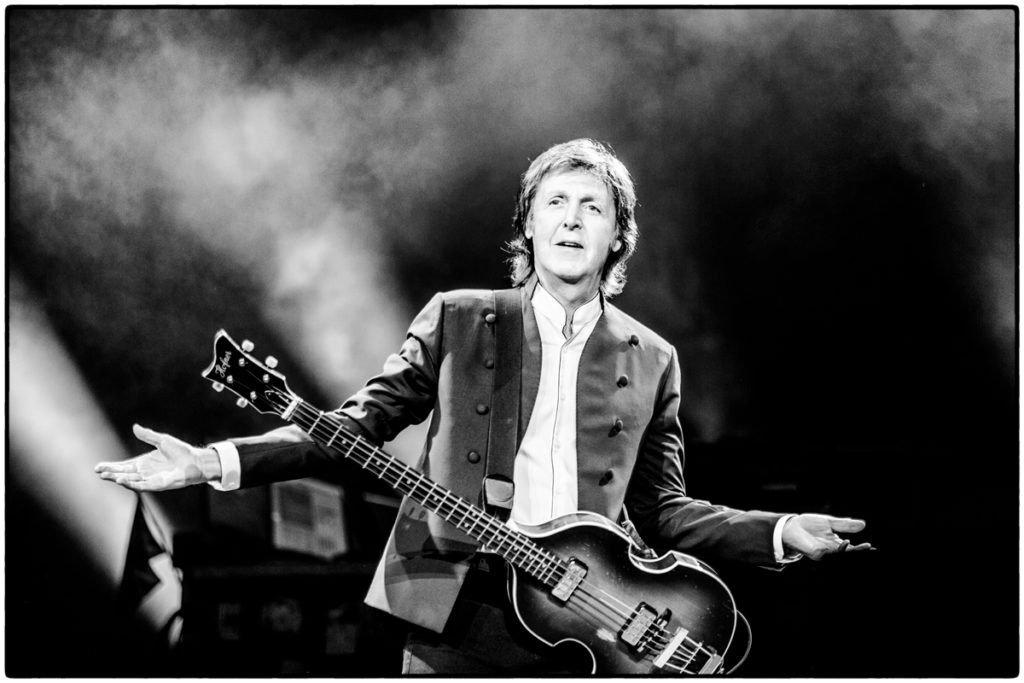

© 2015 MPL Communications Ltd/Photographer: MJ Kim.

To do this we need to go back to McCartney’s first solo album,

From the perspective of 2017 McCartney looks rather different, and not just because it contains ‘Maybe I’m Amazed’, one of the best songs he ever wrote. Still minor, but deliberately so, the contrast between its doodled lyrics and gorgeous but ramshackle melodies suggesting not just a rejection of his superstar status, but a desire to find a new way of making music.

Something similar might be said of RAM, the record he recorded with Linda in 1971 (it’s difficult not to suspect there’s something significant in the fact both Lennon and McCartney chose to make music with their wives after the Beatles broke up). As its opening salvo – McCartney bellowing “Piss off!” – suggests, it is a record made by and for its creator, a defiant celebration of his new life out of the public eye. It is also far more than just a paean to the pleasures of domesticity. The often barbed lyrics (‘Too Many People’ famously pokes back at Lennon’s poisonous ‘How Do You Sleep’, while ‘Dear Boy’ is addressed to Linda’s first husband, Joseph Melville See) lend its cosier tendencies a harder edge than one usually associates with McCartney.

It is in the intricate production, though, that RAM really reveals itself: the layered sound effects of the shimmering rural psychedelia of ‘Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey’ or ‘Back Seat of my Car’, and the movement from the impossibly infectious rock of ‘Smile Away’ (the catchiest song about foot odour ever written) to the seemingly improvised ‘Heart of the Country’ and the joyful absurdity of ‘Monkberry Moon Delight’.

Like McCartney, RAM now sounds like a lost classic. As with Abbey Road or Sgt Pepper the meticulousness of its construction elides itself, making it seem startlingly spontaneous. Its silliness and sweetness lend it an immediacy its maker would only rarely recapture. More importantly, its refusal to follow Lennon down the path of self-exposure and lacerating self-examination (a path the famously guarded McCartney could never have taken anyway) allows McCartney the space to suggest a different kind of pop: one unembarrassed of marrying melody with sweetness and playfulness.

The echoes of this are audible in many parts of contemporary music, but most distinctly in the bucolic indie pop of the 1990s and 2000s (Certainly the line from RAM to Crowded House’s Woodface is not long).

There are glorious songs to be found on many of the albums McCartney recorded with Wings as well, the best of which,

This lurch toward anodyne sentiment is one of the main charges McCartney’s detractors level at him. Yet this obscures a more complex picture. Although Lennon would later dismiss songs such as ‘When I’m 64’, ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘She’s Leaving Home’ as “granny” music, this dismissal, like many of Lennon’s judgements, is too simplistic. As Howard Goodall’s 2017 documentary Sgt Pepper’s Musical Revolution makes abundantly clear, all are extraordinarily sophisticated musical creations that draw, in complex and unexpected ways, upon classical and popular antecedents. More importantly though, their beautifully crafted surfaces disguise and embody complex negotiations with death and loss (that “pretty nurse selling flowers from a tray”? McCartney’s late mother, whose death in 1956 also inspired the teenaged McCartney to write ‘When I’m 64’).

This subtlety is occasionally present in McCartney’s later work. His lovely 1970 single, ‘Another Day’, might well be a sequel to ‘She’s Leaving Home’, the man from the motor trade long-vanished, the runaway whose life only lacked fun now condemned to a life of urban loneliness. Unfortunately this subtlety was increasingly subordinated to something more amenable, even ingratiating.

Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising. The sense of connection that underpins the most universal popular music almost always arises out of a capacity to communicate complex and unresolved feeling – either directly or, as the work of somebody like Bruce Springsteen demonstrates, through a sort of radical empathy for the lives of others. We recognise our own experience in the charge of the performance, feel our own lives in those imagined in song. And while one of the less remarked upon threads through McCartney’s early work is the imaginative empathy of songs such as ‘She’s Leaving Home’ and ‘Eleanor Rigby’, this seemed to become less and less possible for McCartney across the 1970s, and as it did, his music became progressively less urgent.

It’s tempting to suggest McCartney’s seemingly effortless gift for melody is itself part of the problem. In his memoir Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink, Elvis Costello observes that once a melodic shape has been established McCartney will never negotiate about stretching a line rhythmically to accommodate a rhyme. But one might equally suggest McCartney’s later work suffers from a lack of the intellectual sophistication that sustained Bowie or Leonard Cohen or Joni Mitchell, or the political and social project (and perhaps just as importantly, roiling inner drama) that underpins Springsteen’s work.

Simultaneously though, this caricature of McCartney as a bland sentimentalizer misses the sheer weirdness that lurks behind his carefully-cultivated image. Sometimes this weirdness is hidden in plain sight. The uncanny strangeness of ‘Eleanor Rigby’ is as unnerving today as it must have been fifty years ago – but it’s also there in bizarre lapses of taste like ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’, prescient oddities like ‘Temporary Secretary’, the demented ‘Coming Up’ (one of the few of McCartney’s solo songs Lennon admired) or indeed Thrillington, the gloriously bizarre instrumental version of RAM he produced under the nom de plume Percy “Thrills” Thrillington (if you’ve never heard it, seek it out: it’s totally mad and entirely wonderful).

In recent years McCartney has produced a series of albums that suggest a new relationship with his legacy. While none are a

The melodies are still there, and as songs such as ‘Save Us’ (or his collaboration with Kanye and Rihanna, ‘FourFive Seconds’) demonstrate he can still write a radio-friendly pop song with the best of them. But one also has the sense he is no longer in competition with his younger self, that his public admission these records are unlikely to find a wide audience has freed him somehow.

Perhaps we should allow ourselves the same freedom and acknowledge not just his extraordinary productivity, but also the delights of his back catalogue, the best of which looks more impressive with each passing year.

Paul McCartney One on One Tour 2017:

Perth – 2 December, NIB Stadium

Melbourne – 5 & 6 December, AAMI Park

Brisbane – 8 December, Suncorp Stadium

Sydney – 11 & 12 December, Qudos Bank Arena

Auckland – 16 December, MT Smart Stadium

Details and tickets here.