Something has gone awry with the girls in Stellar Leuna’s illustrations.

Looking towards unfamiliar horizons, calling out into the foreboding darkness, full of schemes to run away from home into the arms of tattooed girlfriends. Their eyes are lit up with fear and defiance, sensing a threat beyond the pines. They’re misunderstood and rambunctious, haunted, and wary of authority. Every popular moral panic held toward young girls is vividly brought to life on paper, captured in the mistrustful expressions of these teenagers. Some of them are Leuna too: her younger self anyway.

“There’s a lot of nervous anxiety that inspires my work… it’s what lead me to be an artist in the first place, because I didn’t feel like I fit in anywhere. I remember always wanting to run away as a teen,” she admits. “So if I didn’t draw, what the hell else would I have done with that energy?”

It’s an outsiderism that feels deeply rooted in personal experience. Growing up in deep Sydney suburbia, under the eye of “traditionally Asian [Hong Kong-Chinese] parents with traditional values”, her fantasies took shape in the form of breaking away from expectations and sliding into danger. Experiences birthed an illustrative style of black and white that strikes a balance between the pulpy graphic designs you see on old-school hardcore-punk t-shirts and the sketches from comic books. Equal parts Jennifer’s Body and Death Proof, they carry a certain punkish temper that escapes immediate comprehension. Yet still the comparisons come.

“A lot of people say it reminds them of [Raymond] Pettibon’s stuff… people who don’t read comics but are aware of hardcore punk , that’s the first thing they compare it to… people from all walks of life compare it to different things, like those who are vaguely aware of Frank Miller will be like, ‘It reminds me of Sin City!’”

For that reason she was stunned when approached by Prada to collaborate for their S/S 18 ready-to-wear comic book inspired collection, where they transmogrified her art into a Betty and Veronica inspired milieu. Metal and sub-culture has long been poached by fashion houses for a quick aesthetic, something Stellar is suspicious of, but this interpretation was welcomed. “Working with them never seemed like something that could be possible…. when I got the email I actually laughed out loud.”

My first exposure to her designs was a few years ago on a tote for a Riot Grrrl festival; her illustrations seemed naturally counter-cultural. That her work could be so quickly adapted to one of the biggest European fashion houses speaks of its ability to communicate – a trait she emphasises by depicting the dress of the girls as “generically as possible”. These blank slates are the every girl. The only real fashion influence in her drawings come from herself and her daily uniform. “I don’t consciously try to work fashion into my drawings,” she says. “[I do that] so if you look at it ten years later you don’t think it’s a relic of the time. I’m conscious about clothing in that sense only.”

When I first meet her, it’s a peaceful, sunny day, but she’s wearing the look: black shirt, black boots and black pants. We’re in a less travelled part of Marrickville. We walk past an especially large oval, overlook a river and briefly talk, then head back to her apartment block. As we walk she talks about her escape from the northern beaches to the inner west of Sydney. She seems unsure of how to accept admiration from her followers – but she’s “tickled” that so many people identify with the character and stories in her art. She is frequently approached by women who think the drawings look like them.

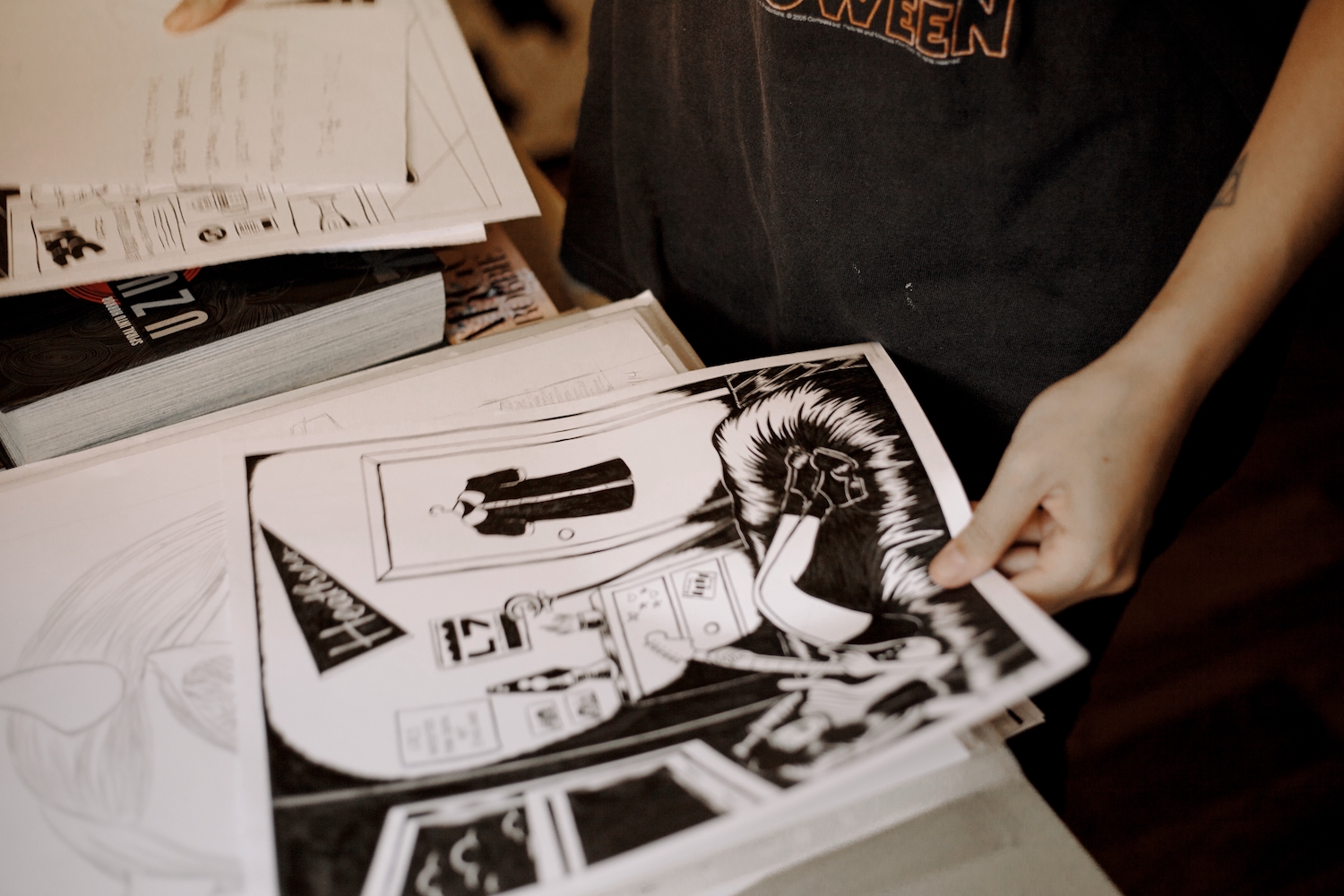

Once home, she shows me her working space, shared with her equally counter-cultural boyfriend. Their influences overlap. The faded photo of Danzig lovingly sticky-taped next to a computer could belong to either of them. Robert Mapplethorpe postcards are pinned alongside lithographs of the Italian masters, and on the other side of the room sit a collection of comic and anime figurines.

You can put two and two together – the emphasis on negative space and clearly defined silhouettes take form from the classics, but the monotone nature of the prints are totally modern. There’s enough Patti Smith adoration present in the room to learn that girls who dress like boys have absolutely bled into Leuna’s vision. It’s strangely sobering to be in her place, and when we kneel on the floor pouring over books, it’s in quiet appreciation.

When I discover the Sailor Moon figurines, still pristine in their packages on the bottom rung of a storage shelf, we are both reverential – for millennial babies, our first exposure to the undeniably Japanese, hyper-feminine magical girl series was nothing less than life-altering. They prioritised female friendship and emotional affluence, showing how secrecy and power influenced even the most ordinary looking of schoolgirls. In those stories girlhood was the most connective, supernatural force possible. Although there’s a more sinister feeling that hangs in the air around Leuna’s girls, you get the feeling they too could flip the switch at any moment and spark a change.