With one last AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH, Tom Wolfe died in his beloved Manhattan last week at the age of 88. The white-suited hustler of ‘New Journalism’ leaves behind a legacy that, if we’re lucky, will inspire new generations of fools to chase his mirages. Born Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr, in Richmond, Virginia, 1930, to a landscape-designer mother and an agricultural magazine editor and teacher father, Wolfe made his name in New York City, from where he let fly with a sweet splatter of journalistic extravaganzas in the 1960s and ’70s.

Wolfe’s signature style drew on jazz, comic books and tabloids screamers, jumping off the page in manic, percussive runs like… well, much like you’d expect from this title of his 1963 Esquire article about the hot-rod scene:

‘There Goes (VAROOM! VAROOM!) That Kandy-Kolored (THPHHHHHH!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (RAHGHHHH!) Around the Bend (BRUMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM)…’

That article headlined his first book, published in 1965. Like many of Wolfe’s thirteen books of nonfiction (notables of which include 1970’s Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, 1979’s The Right Stuff, and 1982’s The Purple Decades), it’s a grab-bag of his lurid magazine-takes on a country supremely high on itself.

“Social autopsies,” Wolfe called them, although he rarely waited for scenes to die before chopping them up. Of his first decade in action, Wolfe said that while America’s novelists had disappeared up their own arses, conducting “frantic little exercises in form”, journalists like him “had the whole crazed obscene uproarious Mammon-faced drug-soaked mau-mau lust-oozing sixties in America to themselves.”

The most lurid of Wolfe’s outpourings is 1968’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, his book about Ken Kesey. Stranger than fiction is an understatement.

Kesey was a small-town Oregon college wrestler who took creative writing at Stanford where he was recruited to the CIA’s MK-ULTRA experiments in LSD (earning the 2018 equivalent of US$620 per acid test). At the same time he worked the night shift in a psychiatric ward, sometimes still tripping. Kesey emerged with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, conquering American literature before dumping writing to form the Merry Pranksters, hippie commandos conducting mass LSD bacchanals and terror-touring America.

Wolfe chronicles Kesey’s Prankster’s from compound-life to travelling the country in a tie-dyed bus (destination ‘FURTHER’) driven by Jack Kerouac’s On The Road-muse, Neal Cassady – via tripping balls at San Francisco’s Cow Palace when the Beatles hit the stage:

‘John and George and Ringo and uh – the other one – it might have been four imported vinyl dolls for all it was going to matter – that sound he thinks cannot get higher, it doubles, his eardrums ring like stamped metal with it and suddenly Ghhhhhhwooooooooowwwwww, it is like the whole thing has snapped, and the whole front section of the arena becomes a writhing, seething mass of little girls waving their arms in the air, this mass of pink arms, it is all you can see, it is like a single colonial animal with a thousand waving pink tentacles – it is a single colonial animal with a thousand waving pink tentacles, – vibrating poison madness and filling the universe with the teeny agony torn out of them. It dawns on Kesey: it is one being … But the head has lost control of the body and the body rebels and goes amok and that is what cancer is. The vibrations of it hit the Pranksters … in sickening waves.’

The book ends before Kesey enters prison. Wolfe, who unfortunately wrote the book without boarding the bus, bolsters his evocative reportage with another breed of acid: a sarcasm born of smugness. Even so, Wolfe might as well have been speaking about his own adventures on the page when he wrote of Kesey’s high-voltage daring: “always comes the moment when it’s time to take the Prankster circus further on towards Edge City.”

The original 1968 cover

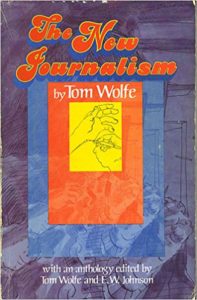

Twenty years after Wolfe published The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, I picked up another book of Wolfe’s that mapped out how a writer might find a way to Edge City: a battered old copy of The New Journalism, his delirious 1973 manifesto-driven anthology. Wolfe’s provocative essays, and the accompanying showcased work of himself and selected contemporaries, stirred the blood. If I could emulate those well-thumbed pages, publishing’s doors and chequebooks would open onto a duly lucrative and idiosyncratic career in reportage.

Like Wolfe’s 1960s and ’70s, this was an interesting time, too. The year 1993… Bosnia was a multi-combatant slaughterhouse, terrorists bombed the basement of the World Trade Center, the US bombed Iraq, David Koresh’s pad at Waco burned to the ground, a certain Black Hawk went down, Pablo Escobar was killed, and Paul Keating won his last ticket to the Lodge.

Wolfe’s manifesto lead me to think that were I sufficiently bold and ambitious; had sufficient curiosity and endurance; felt and thought and danced and fought and read and hiked and talked and wrote enough; if I could keep my shit together through both torment and ecstasy, then I would have the right stuff to create journalism of rare insight and lasting power.

What Wolfe specifically argued for in journalism, and what was doubly needed Down Under, was a revolution in realism. Reportage’s break-through comes about, argues Wolfe, when newshounds don’t just feed the conveyor-belt of churnalism but become hybrid artisans fusing immersive field-work with elaborate, artful prose techniques more akin to novels than reporting conventions.

Of course there are dangers here: dangers that Yale’s examiners of Wolfe’s doctoral thesis twigged to in the late 1950s when he was finishing a PhD in American Studies. The examiners rejected his dissertation about the influence of Communism on American writers between 1928 and 1942. Of Wolfe’s work, the Dean wrote: “The tone was not objective but was consistently slanted to disparage the writers under consideration and to present them in a bad light even when the evidence did not warrant this.” This tendency never left Wolfe, and was evident even in his final book, 2016’s Kingdom of Speech, an ill-conceived, ill-informed poke at Charles Darwin and Noam Chomsky.

Nevertheless, after straightening his thesis enough to satisfy “these stupid fucks”, as he calls his academic superiors in an angry letter, the ambitious hustler became Dr Wolfe. In 1957 he scored a job as a reporter at a small Massachusetts newspaper, then jumped to the Washington Post before landing in 1962 with the New York Herald Tribune, where he paid close attention to the skills and mindset of feature-article writers.

Unlike what he calls “scoop reporters” – rapid-fire newshounds who keep papers afloat in the daily battle to outpace competitors’ coverage of the city’s scandals and dramas – feature writers work slower but longer, tackling stories in far greater depth.

Most anyone I know now with ambition and talent dreams of writing a heavily downloaded app, but in Wolfe’s day his thoughtful and impressive peers aimed to pen a great novel. However, as the ’60s progressed journalism overtook fiction as “literature’s main event,” writes Wolfe. How this got started, according to his self-serving but not necessarily incorrect account in The New Journalism, should prompt any half-decent Australian writer to hunt down the editors of our execrable Sunday papers and go postal. Pour a stiff drink and read this:

‘In terms of experimenting in non-fiction, the way I worked at that point couldn’t have been more ideal. I was writing mostly for New York, which … was a Sunday supplement. At that time, 1963 and 1964, Sunday supplements were close to being the lowest form of periodical. Their status was well below that of the ordinary daily newspaper, and only slightly above that of the morbidity press, sheets like the National Enquirer in its ‘I Left My Babies in the Deep Freeze’ period. As a result, Sunday supplements had no traditions, no pretensions, no promises to live up to, not even any rules to speak of. They were brain candy, that was all. Readers felt no guilt whatsoever about laying them aside, throwing them away or not looking at them at all. I never felt the slightest hesitation about trying any device that might conceivably grab the reader a few seconds longer. I tried to yell in his ear: Stick around! Sunday supplements were no place for diffident souls. That was how I started playing around with the device of point of view.’

Got that? Rather than tightly programming weekend lift-outs with vacuous celebrity PR, motherfucking interior decorators, and flat-out real estate porn, the editors figured what the hell, you writers can let rip and we’ll see what happens. And so in 1960s New York City, there begins a revolution in narrative journalism built on Wolfe’s twin pillars of immersive field-work and novelistic freedom.

‘The Right Stuff’ (1979)

However honest or otherwise Wolfe’s own writing is – and I have considerable doubts about his reporting and think he played it pretty damned safe in times of facing racial violence and injustice – the approach he generally champions is, in the right hands, superb and timeless. Indeed, The New Journalism still carried a potent viral load when I picked it up at a second-hand bookstore in Sydney all those years later.

Sitting at the old Century Tavern high above the corners of George and Liverpool Streets, I read for hours, lapping up the servings of Joan Didion, George Plimpton, Hunter S. Thompson, Robert Christgau, Joe Eszterhas, Terry Southern, and other notables. In particular I marvelled at Barbara Goldsmith’s deceptively unadorned piece, ‘La Dolce Viva’.

Published by New York in 1968, the magazine’s first year of publication, Goldsmith’s deeply unsettling profile of Warhol ‘superstar’ Viva, AKA Janet Hoffmann, was largely comprised of accumulating slabs of Viva’s direct speech motor-mouthed out amid a creeping stench of denial and desperation. Goldsmith exposed the brutal indifference with which the Pop Art maestro reigned over his Factory scene; the artist’s exploitative and offhanded treatment of women emerging as especially problematic, leading Wolfe to cite Goldsmith’s article as “a preface to the incident two months later in which Valerie Solonas shot Andy Warhol and nearly killed him”.

Wolfe reported that advertising space in New York had been “ably sold to high-end retailers on Madison Avenue and elsewhere with assurances of what a high-end magazine it would be and how much people flush with high-end boom money would love it”. In running ‘La Dolce Viva’, founding editor Clay Felker was taking a serious commercial risk, Wolfe notes in his forward to the piece: “his own advertising people had read it and were screaming,” but run it he did.

Felker has been quoted as saying that the article – which Wolfe told him must be published – halved the fledgling magazine’s advertising revenue for the subsequent year. Fifty years later, however, New York survives and boasts one hell of an archive.

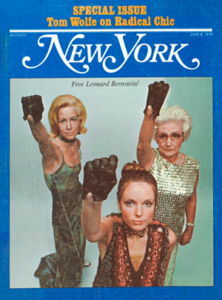

June 8, 1970 issue

In another pointer for Australian editors (and writers), Wolfe is spot on when he writes that interview-stories are usually frustratingly trivial exercises which leave readers saying, “Yes, but what is So-and-so really like?”

Not with the Viva piece, though: not when intrepid New Journalists such as Goldsmith have the curiosity, endurance, and integrity to stick with their subjects until, as Wolfe says, the writers can “answer the question with greater frankness than ever before”.

Writing this now, I can’t help but think of how successfully Australia’s fucking PR industry, defamation laws, non-freedom of information, widespread cultural aversion to questions, and the shallow, craven, junket-hungry nature of so many journalists and editors combine to keep frankness and readers worlds apart.

The exceptions here are rare enough to resonate for years. One I still think about came in the early ’90s: Antonella Gambotto’s unflattering profile of actor Noah Taylor for Mode magazine. The article sparked panic in the Australian film and TV scene and a furious reaction from Taylor because Gambotto made readers aware that the then-A-list star had a drug habit (a clean Taylor would later admit he’d had problems). Perhaps when a real history of Australian film is written – most particularly the oddly quiet years of some of its greatest talent – what’s sometimes presented in profiles as a laconic indifference to success will be updated to a strong partiality to narcotics.

Yet the point is not that we need bombshells of failure, contradiction, weakness and sin in all our reporting. It’s that we need real life, and that comes with failure, contradiction, weakness and sin. Such realities aren’t destined to be bombshells unless the ugly stuff gets smugger and uglier the longer it goes unreported, or locks away a crucial truth while the public are fed gleaming presentations of hypocritical artifice. Then the megatonnage builds.

When it detonates, think of Sharri Markson’s exposure of Barnaby ‘Beetrooter’ Joyce, and the astonishing revelations about Don Burke that Tracey Spicer coordinated. Better late than never, of course, but how much better would everyone be served if the press routinely rolls with in-depth, fleshed-out, accurate portraits and accounts like these.

How much better informed would we be – how much more realistic our takes on life and society – if New Journalist-Anthropologists routinely trawled the country, infiltrating deep beneath the surface, feeling at least as much as they observe, and considering the flow between the eyes and heart? As it stands, I read the news and see little but grab-bags of quotes, stats, decisions, alleged trends, hype, crimes, and claims. It’s shallow, piecemeal and devoid of real humans in all their nuanced, elusive, vexing complexity. For a voting citizen like me, contemporary Australian journalism does bugger all to equip us to make decisions that affect other people.

Some of those people are, of course, in countries where Australia’s armed forces get busy with minimal press scrutiny outside brief, hyper-controlled PR exercises staged for select journalists. The New Journalism, by contrast, contains a range of relatively freewheeling, very un-PR accounts of the US’s often haphazard campaign in Vietnam: Nicholas Tomalin’s ‘The General Goes Zapping Charlie Cong’, John Sack’s ‘M’, and Michael Herr’s ‘Khesanh’ (which would eventually form a chapter of Herr’s hugely influential reefer-cloud of Vietnam reportage, Dispatches (1977). The recent round of wars have also produced a stack of eye-opening reportage from many US writers; one such article – Michael Hasting’s ‘The Runaway General’, published in Rolling Stone – even triggered the resignation of the overall commander of US and international forces in Afghanistan in 2010.

Wolfe writes that for his anthologised champions to bring life to the page, they have to pursue methods “more intense, more detailed, more time-consuming than anything that newspaper or magazine reporters, including investigative reporters, were accustomed to”.

These artists of reportage “developed the habit of staying with the people they were writing about for days at a time, weeks in some cases,” writes Wolfe. “They had to gather all the material the conventional journalist was after – and then keep going. It seemed all important to be there when dramatic scenes took place, to get the dialogue, the gestures, the facial expressions, the details of the environment.”

Being there, really being there, is more likely to happen when one’s approach to journalism is akin to cooking’s slow food movement. How much easier it is, however, to auto-fill pages with politicised snapshots, analysis written from a great distance, or even worse, ghost-written commando shlock.

Australia does have its intrepid handful of journalists trying to publish immersive revelations of life and death amidst the wars this country has been waging for the past 17 years. Covering the costs, however, is beyond most freelancers, even if they’re running shoestring operations compared to corporate correspondents. And while some staff journos want to let tap into their inner New Journalist, within Australia’s big, risk-averse media companies, roles and mindsets can be so fixed that reportage often seems to run more to program than merit.

Back in the mid 2000s when I was a reporter at the Sydney Morning Herald I mentioned to then-editor Robert Whitehead that I was heading to the southern Philippines’ jihadist zones in my holidays – in what would be my second such trip – and would be happy to offer the SMH a story from it. Whitehead not only rejected it out of hand, he said if I made the journey then I would have to find a new employer. It’s too dangerous, he said, and it would be breaching seniority. Paul McGeough was the only correspondent he wanted near conflicts, especially given McGeough’s annual insurance bill of several hundred thousand dollars.

The MEAA union reps went to water (“maybe Robert’s right”), but before I flew out regardless, a few staff photographers – a more intrepid bunch than writers – let it be known Whitehead’s decree stank, and he backed down. That’s when I began to see the SMH as a simulation of a newspaper, an impression that grew and grew until I left the paper to pursue New Journalism ideals.

First edition cover, 1973

Save me, Tom Wolfe, save me. Use the heavenly powers you’ve surely gained since checking out of this Insta-fucked era. Please, you exasperating, angelic, con-artist corpse-dandy; transport me back into 1960s and ’70s New York for those Purple Decades of star-spangled madness on the streets and publishing’s electrifying risk-taking.

If you can’t do that, then wipe clean my mind. The infection I caught from The New Journalism so fuelled my drive to write that until recently I never noticed your whole thing depends on you having been where you were, when you were, and with whom you were. Come to Australia and try it; maybe you too will be piecing shit together with bits of casual work and paltry pay-rates for writing that’s “more intense, more detailed, more time-consuming” than any sane person would attempt.

Perhaps Hunter S. Thompson had good reason to call you a “thieving pile of albino warts” in a letter sent while you were sorting out his inclusion in the 1973 anthology. He doesn’t mince words: “I’ll have your goddamn femurs ground into bone splinters if you ever mention my name again in connection with that horrible ‘new journalism’ shuck you’re promoting.”

Fuck Thompson. I’ll take that horrible shuck anyday over much of what I see around me (just don’t get me started on Wolfe’s run of fiction that began with 1987’s novel, Bonfire of the Vanities). So for those of us subsisting in shanty-towns on the far perimeters of New York’s empire of prose, whose provincial editors play it maddeningly safe, but who nevertheless have the infection, what choice is there but to let this madness take its course.

Last call for Edge City. Who’s coming?