Within the mangle of wire-mesh fencing and low, bright orange hard-plastic barricades housing the long hole along George Street that will someday transform into Sydney Light Rail, there are tools, frequently downed, along with a sparse scattering of workers.

According to news reports, the project has been on a “go-slow” for much of this year due to a dispute between the Spanish-based construction company Acciona and the NSW Government. A $1.1 billion lawsuit brought by Acciona against the NSW Government is now before the courts.

The go-slow is a mixed blessing for those of us who, since October 2015, have been daily dodging our way around the construction on our way to work. In those first months, cheerful, young, often Irish-accented workers wearing helmets and hi-vis coats were on hand to restrain pedestrians in business clothes from death dashes. Ankles have twisted, horns blasted, lights been run, tempers frayed – more than usual for the CBD – in the interim. We’ve put up with it because we are building tomorrow’s Sydney. We must do our bit. That’s life in the big city. We’re not anti-development, we’re just… exhausted.

Before the go-slow, when the banging and drilling and dust and vibrations were at peak production levels, I asked a young pony-tailed barista from the George Street window of a café how she was coping. Making a gun with her thumb and forefinger, she pointed at her temple. If a sound came out when she exhaled with force, I couldn’t hear it.

Fortunately, we are now habituated. Deadline after deadline has blown out, reportedly due to complexities, not predicted, with power and water utilities underground. This, apparently, is a common phenomenon with large transport infrastructure projects all over the world whereby over-optimism and underestimation regarding budgets, time-frames and problems are rife.

So, for now, the mangle and traffic chaos remain in Sydney, although it’s sure quieter out there right now. Still, everyone’s been asking the same question: when will it end? None more so than independent Sydney City Councillor and the co-owner, with her brother Con, of Vivo Café on George Street, Angela Vithoulkas. Vithoulkas tells me income from their business has dropped 30 per cent since the works began. “We are humiliated, economically devastated. We will never recover,” she says.

Vithoulkas has been a key convener of a group of businesses and residents adversely impacted by the light rail project in the CBD. Many have now registered their details to become part of a class action to sue the NSW Government for damages. “We’ve had a lot of legal advice and we’re being courted by several of the major law firms,” she said. She is also behind a new political party representing small business interests. It will target Upper House seats at the next NSW State Election.

Vivo is just one of an estimated 1,500 businesses with shopfronts along the light rail construction route, many with stories of personal stress and commercial loss. Vithoulkas’s goes like this: “My brother and I bought the café 15 years ago. We turned it around to become one of the most awarded businesses in the CBD.” In the early 2000s, Vivo won six awards, including City of Sydney Business Awards for Outstanding Café of the Year and Outstanding Business of the Year. In 2007, Angela also won the Telstra New South Wales 2007 Women’s Business Owner Award. She says the business continued to prosper until October 2015. When the light rail works started, day-trippers, including many older people and mothers and their children who once came to the café, stopped coming. Where Vivo could once be seen from many vantage points, the construction paraphernalia has made it barely visible. Access is another issue. Buses and other vehicles once delivered customers along the route. But it’s a decent walk from anywhere to get there now. “We only get locals. We’ve lost our destination traffic,” Vithoulkas says.

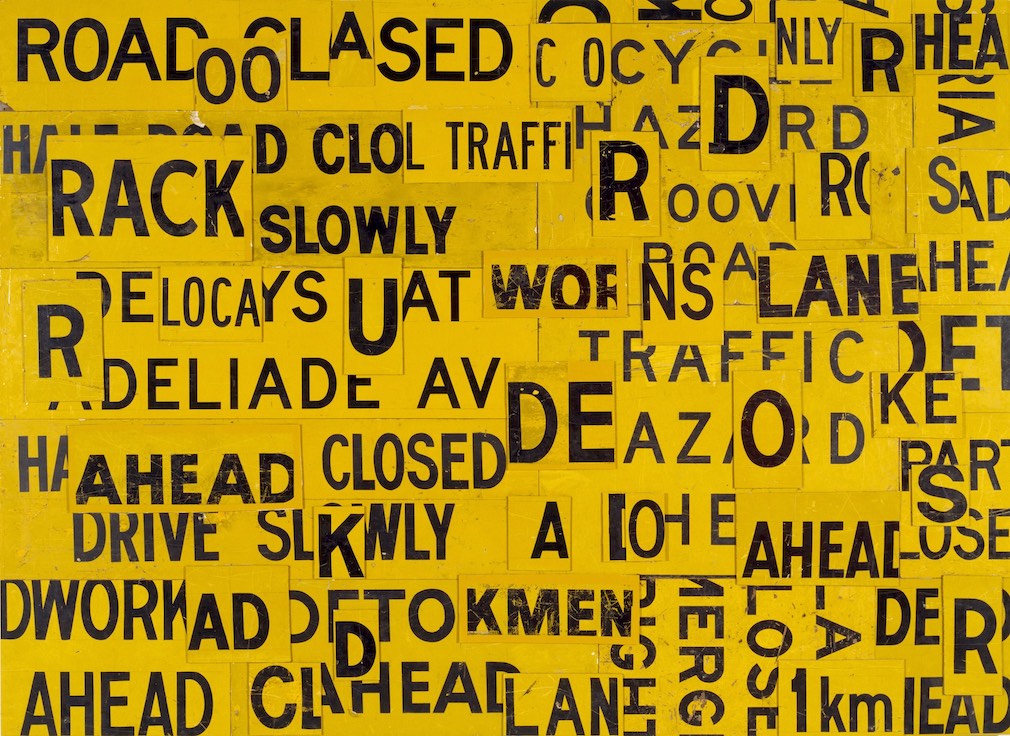

Vithoulkas says George Street, “the spine of the city” has become “a garbage dump and a parking lot”. While Transport for NSW has created a ‘Small Business Assist’ program to help deal with the construction’s financial impact – the State Government says it has provided financial relief to more than 60 businesses affected for longer than expected – Vithoulkas says the criteria for assistance are unclear and the compensation inadequate. “The Government has gone in ill-prepared and unwilling to mitigate what is happening.”

In the arcane world of transportation research, Peter E.D. Love from the Department of Civil Engineering at WA’s Curtin University, alerted me to a theory called Hirschman’s Hiding Hand. It is a “principle that suggests when the public sector decides to undertake a project, the ignorance of future obstacles allows them to rationally choose to undertake it, and once it is underway they will creatively overcome the difficulties that may arise as it is too late to abandon the project.”

This, I realise, is what the whole of Sydney is going through – and not just with Sydney Light Rail.

Edinburgh had a similar experience with its light rail. The Edinburgh Trams project was originally estimated to cost £320 million. The project was finished three years late at a reported construction cost of £776 million. Contractual changes and complexities have led to a revised estimated final cost of over £1 billion. “Projects of this nature are complex and the in-ground services always pose challenges. You see we don’t know where they are,” Love said.

Much of the quarrel with Sydney Light Rail appears to be with the way the project has been handled by government, rather than with the concept itself. Light rails, once finished, have many benefits. According to Love, they typically include comfortable rides for passengers, the aesthetic appeal of well-designed trams, potentially higher passenger capacity per lane per hour in the right conditions, lower noise levels, good integration with pedestrian malls and the fact that it’s politically easier to remove cars from a street if buses are also removed. And the pedestrianisation of main thoroughfares does bring new life to cities.

But few could dispute this project has been disorganised and poorly managed from the beginning. A NSW Auditor-General’s report in 2016 painted a damning portrait. It noted the planning and governance arrangements, “while approved by the NSW Government, skipped important assurance steps. Tight time-frames meant planning was inadequate and normal governance systems were not initially in place.” Crash or crash through, seems to have been the ethos. Meanwhile, some argue, global construction companies routinely underquote for the cost of major infrastructure projects to land the jobs. Once the project is underway, problems arise. Costs and timelines blow out. Everyone starts pointing fingers.

The impact on businesses is only half the story. Walking along Devonshire Street, late on Saturday night, after seeing a play at Belvoir, I am hit by the full horror of what residents are going through. Beautiful Victorian terrace houses along a once iconic strip of restaurants and inner-city chic are now a dress circle for in-ground craters and heavy-duty earth-moving equipment that have killed the street life, even if only temporarily.

Sydney residents whose homes are along the light rail construction route have a whole different world of pain. “There are days when the area around the house is a dust bowl. There’s a big hole and when they’re drilling, the whole house is shaking,” said one resident who did not want to be named. She said three years of noise and dust had left her stressed and anxious. Affected houses were subjected to pre-dilapidation reports, which residents understood would result in reparations for damage caused. “But when cracks in our house got worse we contacted Acciona who said, ‘It’s not because of us’,” said the resident.

She said she was pleased the Minister for Transport and Infrastructure Andrew Constance had begun to take an interest in the residents’ plight. Constance recently met with a group of affected business owners and residents at NSW Parliament House. Lisa Prestwidge, who lives on Anzac Parade, was among them. Prestwidge and her daughter, who is doing the HSC this year, have been living with the construction noise for 15 months. “We’ve had three noisy nights this week. Sometimes they turn up at 3am and start working with the compactor which is supposed to be ‘less noisy’ – 83 decibels – than the jackhammer – 85 decibels,” Prestwidge says.

Noise-cancelling headphones and alternative accommodation are among the assistance offered to Prestwidge and her daughter, who have so far spent one night at a hotel. “We can’t wear the headphones to bed and we don’t want to keep having to up stumps all the time,” Prestwidge said. She is now hopeful the Government will assist with double glazing and air conditioning for her unit. This remedy has been offered to some but not all residents.

According to ALTRAC Light Rail’s Stakeholder Relationships Manager Erika Jimenez: “Individual properties are assessed across the light rail alignment and, where required … offered treatments to their properties according to the level of operational noise likely to be experienced.” Jimenez said civil construction of the light rail will be “substantially completed by the end of this year”. She added, “The next phase of works involves systems installation and testing and commissioning.”

While Angela Vithoulkas expects this next phase to take an additional year, any end date will now be too late for her business. She recently learned the lease for Vivo’s premises has not been renewed.

On a wintry afternoon in George Street, near Circular Quay, I come across a couple of construction workers moving a gate across a section of the road to free it up. I ask what it’s like working on the light rail project. “Not us,” they say, as they point to a cavity away from the road. “We’re working on the 55-storey office/retail tower. We’d have finished hours ago if we were on the light rail.” Tensions, the men tell me, sometimes flare up between the different teams of builders, all with competing needs, on the same bit of turf. On so many levels in so many places, we are a city besieged by construction.