“Well, you play that tarantella,

all the hounds will start to roar…”

Tom Waits, ‘Tango Till They’re Sore’

When I was a kid there was a whole underground world of ‘New Australian’ booze-making that I fear has disappeared.

Today when I see folks discussing their wine with sommelier-like crapulence I know I’d rather a Vegemite jar of Black Charlie poured from an old DA bottle, followed by Mrs Polluzzi’s duck egg linguine, all washed down with my father’s home-made limoncello or an espresso stained with his bespoke sambuca or amaretto.

Back in the day ‘special lemonade’ is what you used to ask for at a particular bottle-o in Strathfield, or a delicatessen in Leichhardt, and various other locations around the Inner West where you could get the key ingredient for home-made amaretto, limoncello, sambuca or Tia Maria. This was part of growing up on the edge of Sydney’s Inner West – home-made Italian alcohol.

My father slaved away all week at a biscuit factory. First at Peek Freans in Ashfield (now the ginormous Bunnings on Parramatta Road) where he’d been tied to their wagon wheel, and later at Arnott’s – just a 15 minute walk away at dusk or dawn, depending upon the shift. We had all the Tim Tams we would ever need in the spare fridge down in the garage. The other thing the spare fridge kept, beside the odd leg of prosciutto, was booze.

Dad had his booze work-bench – an old desk he’d picked up somewhere – and on the weekend after blowing some wages in a smoky Burwood TAB we would get together and cook up some bespoke alcohol. What could be more wholesome for a child than to help his father make illegal spirits?

First of all you needed the ‘special lemonade’, which was essentially pure alcohol. Where it was distilled nobody seemed to know or care. But at around $6 for a 1.25 litre recycled lemonade bottle of it, from which you could blend three or four bottles of liquor, it was good value.

Once you’ve got your alcohol base you grab your flavouring agent. These came in the form of little packets not much bigger than a box of Redheads called La Strega (The Witch). The Redheads comparison is appropriate as traditionally redheads, especially ones with green eyes, are considered witches in parts of southern Italy. La Strega packets had the classic hag-witch visage on the cover. Looking for these distinctive boxes as you perused a deli, bottle-o or shoemaker was one way of knowing whether or not this establishment might have ‘special lemonade’ under the counter.

Now you have your main ingredients you get yourself a pasta pot, fill it with boiling water, and stick a shitload of sugar in it. Half a supermarket packet, or something like that. My dad was usually availing himself of the spirituous produce of previous cooking sessions during this mixing process – measurements were intuitive, to say the least.

However my father assured me that as a professional biscuit factory boilermaker he knew what he was doing. The Di Fonzos, after all, had survived the war through their alcohol-making talents. My father still relates the tale of how as a child on my great-grandfather’s vineyard in the Abruzzi mountains during World War II, when the occupation by first German and then American troops meant the staples of life were in short supply, he would be sent by his nonno to the chef of the occupying army of the day with a jar of Di Fonzo home-made grappa. The army chef would always readily barter with ingredients from the army stores. Money might talk but in times of war a good shot of grappa screams.

Back at the work-bench you’re dissolving your shitload of sugar in your pasta pot of water boiled in the grease-stained garage kettle. Now you’re ready to mix in a portion (maybe a third or quarter) of your ‘special lemonade’ and then pour it all into a bottle. Preferably an old Galliano, whisky, cognac or at least wine bottle.

However as production increased, and with the introduction of Black Charlie wine (which we will touch upon later) such bottles would run dry, so my father had, in a moment of full assimilation, bought himself a beer bottle capping machine from a home brew shop. He wasn’t averse to an ale himself, especially after working on the house or yard, his shirtless back peeling layers of burnt skin in days when we never knew the word sunscreen. Empty longnecks were always around.

If he ever ran short he could shout over the fence to Mr Polluzzi who always had a ready supply of empty Resch’s DA (Dinner Ale) longies available. Dad joked that a lot of ‘New Australians’ bought DA because it was the easiest one to pronounce. He had a lot of lines like that.

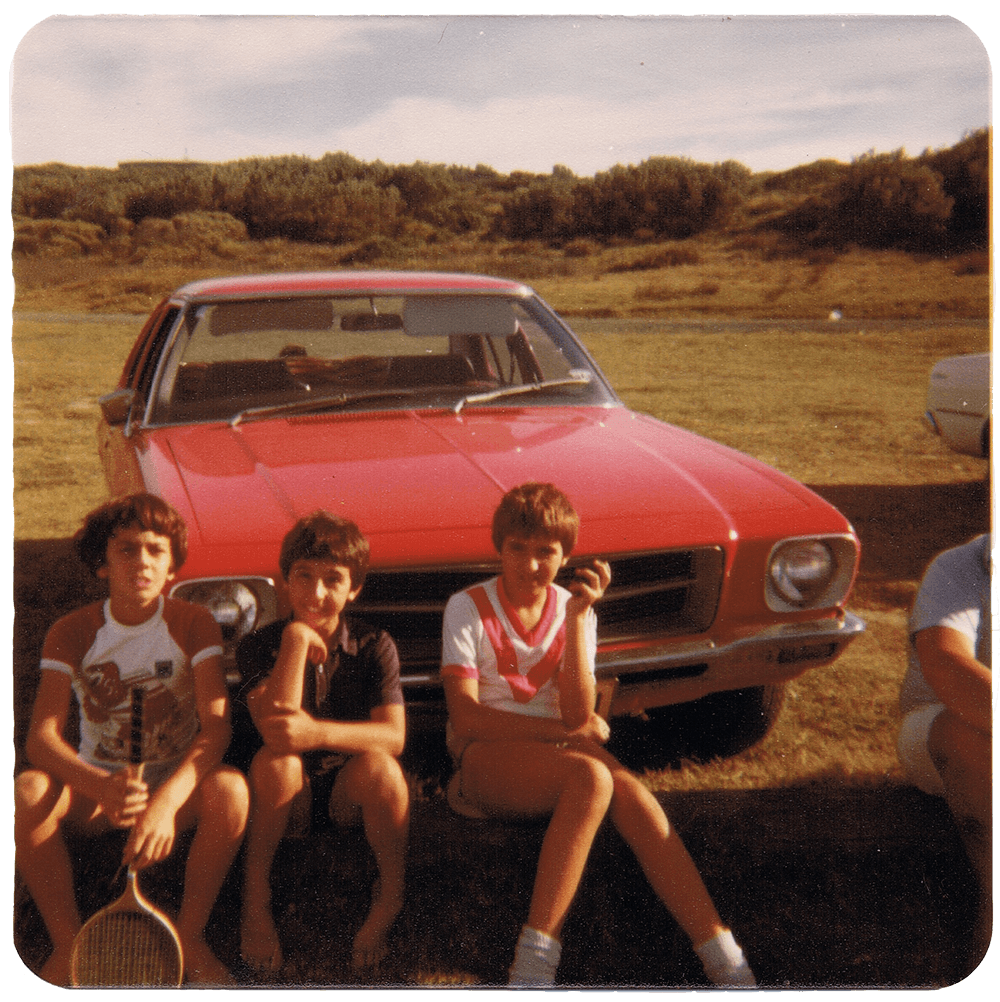

Along with one-liners he had the odd song of his own he used to sing. He didn’t believe in having a radio in the car, they distracted from driving (of which he still boasts an unblemished record despite his cabby years). Hence our fire-engine-red Holden Belmont forever had the plastic radio compartment-cover sealed tight like it was the day in 1972 when we bought it down Parramatta Road. If music was needed on a drive he could pump out his infamous ditty about my Irish-Australian mother. All were encouraged to sing along with this delicate tarantella that went…

“Yackety-yack, blah-blah, blah-blah.

Yackety-yack, blah-blah, blah-blah.

That’s all I hear all day.

Yackety-yack, blah-blah, blah-blah.” (repeat till bored.)

Naturally he meant it all in a loving way.

The remains of Senior Di Fonzo’s booze-making station AKA the garage. Photography by Melita Rowston.

So now pour your sugar, alcohol and water mixture into an old bottle and choose your La Strega flavour packet. Sambuca was the regular go-to, followed by Amaretto. Among others we tried were the whisky flavour, which created what was to this day the worst whisky I’ve ever tasted. Best do like a band at La Gondola Reception Centre in Five Dock and stick to the trad Italian numbers.

Of course if you’re making limoncello, arancello or Tia Maria a different process takes place. For limoncello you replace the water with freshly squeezed lemon juice, no La Strega necessary. Arancello is the same thing but with oranges. My father insisted on only home-grown lemons or oranges from our backyard, which meant braving the heat, spiders and stink-bugs whilst picking them.

Likewise Tia Maria involved replacing the water component with espresso. What with the strength of the alcohol, which I would estimate at around 50 per cent, and the espresso coffee, the Tia Maria hit you like a speedball with your body not knowing whether it was coming or going.

There were no preservatives in the limoncello or arancello. Hence a worrying skin of mould sometimes grew on the citrus pulp floating atop if cellared, or rather garaged, for long. A good shake of the bottle hid this from any guests and my father assured me once again, as a professional biscuit factory boilermaker, that the alcohol levels would be more than enough to kill any pesky fungus.

My father insisted that all his spirits be aged for at least 15 minutes, sometimes longer. This aging process was measured by my father puffing on a Dunhill Red whilst using the never-washed garage knife to slice prosciutto or secure an anchovy.

A nice shake of the bottle, and some chilling in the case of limon or arancello, and it’s ready to be given to the first person who sets foot on the property. My parents are now in their mid-80s and too old for such shenanigans. But until these last few years no one could visit Conway Avenue without taking home a few bottles of home-made sambuca, amaretto or limoncello after a fine tasting and a meal that would bloat a boa constrictor. And perhaps a bag of slightly-askew factory-reject Tim Tams.

La Strega. Photography by Melita Rowston.

The other bottling involved the aforementioned Black Charlie. Once a year my father and uncle would drive out to Liverpool to visit an old Sicilian known as Black Charlie who made the best vino out there in semi-rural suburbia. There seemed a theme, even at Homebush Boys High, of Italians of Sicilian heritage being nicknamed ‘black’ because of their darker skin. There’s a joke from a Tarantino script there but I’m not touching it.

Black Charlie made his plonk on his farm probably not too far from where the Milat brothers sheltered from their Croat father’s beatings in a farmhouse with no door or window facing the street. Perhaps the Milats drank Black Charlie? If so I wouldn’t hold it responsible for anything. The Tia Maria on the other hand…

According to my father, every Italian in Sydney knew when it was time to make the long, hot drive out and pick up a couple of barrels of Black Charlie. There was Black Charlie red and Black Charlie white. Nobody seemed to know or care what kind of grape it was. Following the European geographical system they would both be termed ‘Liverpool region’ in style. Personally I can’t imagine the fine burghers of Mosman ever arguing over the pros and cons of a room-temp Warwick Farm versus a chilled Casula.

The barrels were around 50 litres and looked like the barrels industrial cleaning chemicals came in (I’m sure it was all perfectly sanitary). And this is really where the beer bottle capper became necessary – the wine had to be sucked through a tube and then into a DA bottle on a non-liquor-making Sunday, just as God intended.

In later years, when I visited my olds they would give me bottles of Black Charlie which I enjoyed taking to parties in Newtown just to see people’s reactions to its taste. You either loved it or hated it. It’s what wine must have tasted like in the days of ancient Rome when it was drunk in lieu of the filthy water, and when there were no such things as preservatives, chemical flavourings and health regulations regarding feet. It was basically old grape juice, and that’s pretty much what it tasted like, but you could feel the devil alcohol dancing underneath.

People still ask me at parties when I can get another bottle of Black Charlie or my dad’s limoncello. They say they never tasted anything like it before or since. I think they mean it as a compliment, but sadly Black Charlie has gone to the great vineyard in the sky.

Dad’s still alive but his Holden Belmont was sold a few years ago as his days of driving and cooking liquors are behind him. The car was in great nick, having been garaged for most of its 40-odd years. I’m sure it was the only Belmont sold with its radio-compartment still sealed, the faint echo of a politically-incorrect tarantella forever echoing through the seats.