O wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world,

That has such people in’t.

— William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act V, Scene I, ll. 203–206

Take a walk through the land of shadows

Take a walk through the peaceful meadows

Don’t look so disappointed

It isn’t what you hoped for, is it?

– Talking Heads, ‘Memories Can’t Wait’

You Xiaoli was standing, precariously balanced, on a stool. Her body was bent over from the waist into a right angle, and her arms, elbows stiff and straight, were behind her back, one hand grasping the other at the wrist. It was the position known as “doing the airplane”. Around her neck was a heavy chain, and attached to the chain was a blackboard, a real blackboard, one that had been removed from a classroom at the university where You Xiaoli, for more than ten years, had served as a full professor. On both sides of the blackboard were chalked her name and the myriad crimes she was alleged to have committed….

The scene was taking place at the university, too, in a sports field at one of China’s most prestigious institutions of higher learning. In the audience were You Xiaoli’s students and colleagues and former friends. Workers from local factories and peasants from nearby communes had been bused in for the spectacle. From the audience came repeated, rhythmic chants … “Down with You Xiaoli! Down with You Xiaoli!”

“I had many feelings at that struggle session,” recalls You Xiaoli. “I thought there were some bad people in the audience. But I also thought there were many ignorant people, people who did not understand what was happening, so I pitied that kind of person. They brought workers and peasants into the meetings, and they could not understand what was happening. But I was also angry.”

.– Ann F. Thurston recounting professor You Xiaoli’s ‘struggle session’ in her book Enemies of the People – Wikipedia entry on ‘Struggle Sessions’, Cultural Revolution, China.

Panchen Lama during the struggle (thamzing) session in 1964. Photography by Unknown [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

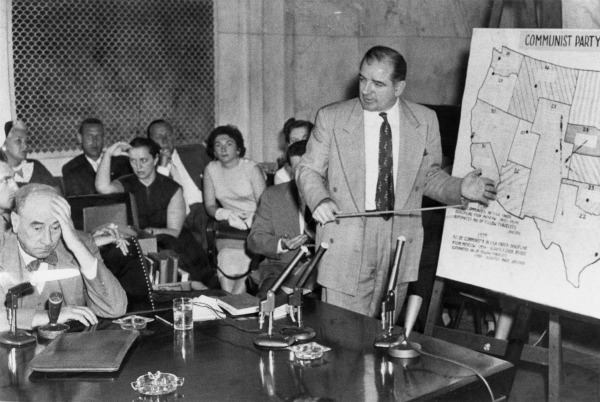

Miller recalled the source of his creation while watching the filming of the new movie of “The Crucible”. When he wrote it, Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Comittee on Un- American Activites were prosecuting alleged Communists from the State Department to Hollywood; the Red hunt was becoming the dominant fixation of the American psyche. Miller did not know how to deal with the enormities of the situation in a play. “The Crucible” was an act of desperation; Miller was fearful of being identified as a covert Communist if he should protest too strongly. He could not find a point of moral reference in contemporary society. Miller found his subject while reading Charles W. Upham’s 1867 two-volume study of the 1692 Salem witch trials, which shed light on the personal relationships behind the trials. Miller went to Salem in 1952 and read transcripts. He began to reconstruct the relationship between John and Elizabeth Proctor and Abigail Williams, who would become the central characters in “The Crucible”. He related to John Proctor, who, in spite of an imperfect character, was able to fight the madness around him. The Salem court had moved to admit “spectral evidence” as proof of guilt; as in 1952, the question was not the acts of an accused but his thoughts and intentions. Miller understood the universal experience of being unable to believe that the state has lost its mind…

Jean-Paul Sartre wrote the screenplay for the first film adaptation. The play gets produced around the world in times of political upheaval. Its message lends itself to accusations as contemporary as sexual abuse. “The Crucible” evokes a lethal brew of illicit sexuality, fear of the supernatural, and political manipulation, a combination not unfamiliar these days. The film, by reaching a broader audience, may unearth still other connections to those buried public terrors that Salem first announced on this continent. The crucial damning event in those trials was signing one’s name in “the Devil’s book”. Nobody thought to ask what this meant. The thing at issue was the secret allegiances of the alienated heart, always the main threat to the theocratic mind, as well as its quarry.

– ‘Life and Letters’, The New Yorker, October 21, 1996 P. 158. Preview notes on Arthur Miller’s article ‘Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible’.

Welch-McCarthy Hearings, 9June 1954, by United States Senate [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Lydia Ivanovna has influence among the appointers, and Oblonsky figures he might as well use the occasion to charm her into helping him. Thus, while listening to Lydia Ivanovna and Karenin’s odious religious palaver, he cravenly – but, he hopes, not too cravenly – hides his aethism:

“Ah if you knew the happiness we know, feeling His presence ever in our hearts!” said Countess Lydia Ivanovna with a rapturous smile.

“But a man may feel himself unworthy sometimes to rise to that height,” said Stepan Arkadyaevich, conscious of hypocrisy in admitting this religous height, but at the same time unable to bring himself to acknowledge his free-thinking views before a person who, by a single word to Pomorsky, might procure him the coveted appointment.”

– Janes Maclcom, ‘Dreams and Anna Karenina’, New York Review of Books, June 25-July 8, 2015, pp.10-12

The book’s red cover is scraped raw by [Valerie] Solanas’s black pen marks. She’s crossed out her own name under the title with such vigor that in places the white pith of the paper cover shows ragged through the red and black. Drag the pad of your finger over it, you’ll feel the torn surface. Beside it, she’s written “by Maurice Girodias,” as if to reassign authorship to her publisher. Her name, though, is still legible—the act of defacing was more important than the actual erasure of information, as if she can’t decide between protesting the personal (male) affront and asserting her authorship. In fact, annotation allows her to do both at once.

–Cory Tamler, Annotating and Becoming: Valerie Solanas on Valerie Solanas, September 2017. A student of the PhD Program program in Theatre at the Graduate Center, CUNY, Tamler brings her background in performance studies to critically examine Solanas’ self-annotated copy of the SCUM Manifesto. A radical feminist work, SCUM Manifesto was published in 1967 – just one year before the author would attempt to assassinate Andy Warhol.

Grave of Valerie Jean Solanas 1936-1988. Saint Marys Catholic Church Cemetery, Fairfax County, Virginia. Photography by Sarah Stierch [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Garner is, above all, a savage self-scrutineer: her honesty has less to do with what she sees in the world than with what she refuses to turn away from in herself. In “The Spare Room” (2008), her exacting autobiographical novel about looking after that dying friend, she describes not only the expected indignities of caring for a patient—the soaked bedsheets, the broken nights—but her own impatience, her own rage: “I had always thought that sorrow was the most exhausting of the emotions. Now I knew that it was anger.”

– James Wood, ‘Helen Garner’s Savage Self Scrutiny’, The New Yorker, December 12, 2016 issue.

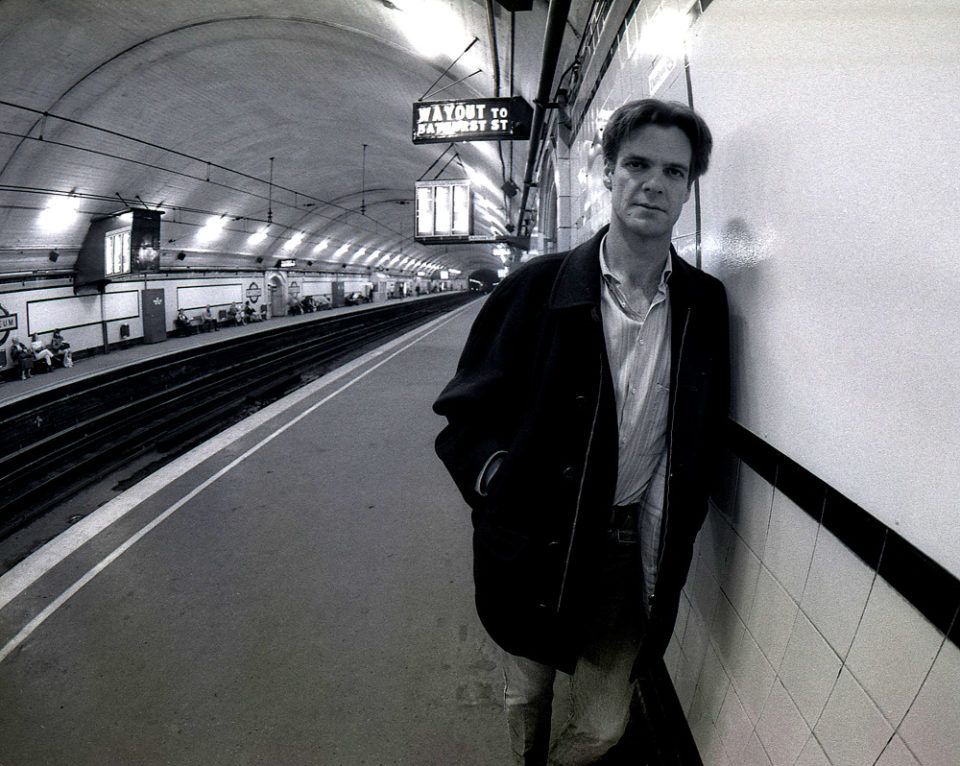

Should we stop reading these writers who’ve done horrible things?

“It’s a valid question. I don’t think there is a straightforward answer, but I would draw a distinction between choosing as a reader and choosing as a critic. As a reader, choosing not to read a writer for any reason is absolutely valid. But I’ve noticed that some critics and scholars have said they’re not going to assign Wallace. Other writers, like Junot Díaz and Sherman Alexie, also come to mind. But the question goes way back. You have Woody Allen and Roman Polanski and Caravaggio for that matter. So this is something that arises again and again, but I’ve noticed this critical decision has been made publicly with Wallace in particular. An obvious example is Amy Hungerford, who’s talked about refusing to teach or assign Wallace anymore.

“It doesn’t seem to me that this is a valid critical gesture because if you are lucky enough to be in a position to teach and design your own syllabus, no one’s going to notice if you leave a writer off. Inclusion can be radical, but to not include a writer — unless you are going to talk about the reason for not including them, in which case you might as well include them — is not a visible critical gesture. I think what happens when you do that as a critic — and as a teacher particularly — you polarize debate. I know young, early career female scholars of Wallace who have been strongly criticized by other feminist scholars for studying Wallace at all. So those gatekeeping rules seem to me to be very counterproductive, critically speaking.”

– Steve Paulson, ‘David Foster Wallace in the #MeToo Era: A Conversation with Clare Hayes-Brady’, LA Review of Books, September 10, 2018.

David Foster Wallace at reading for Booksmith at All Saints Church in 2006. Photography by Steve Rhodes [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

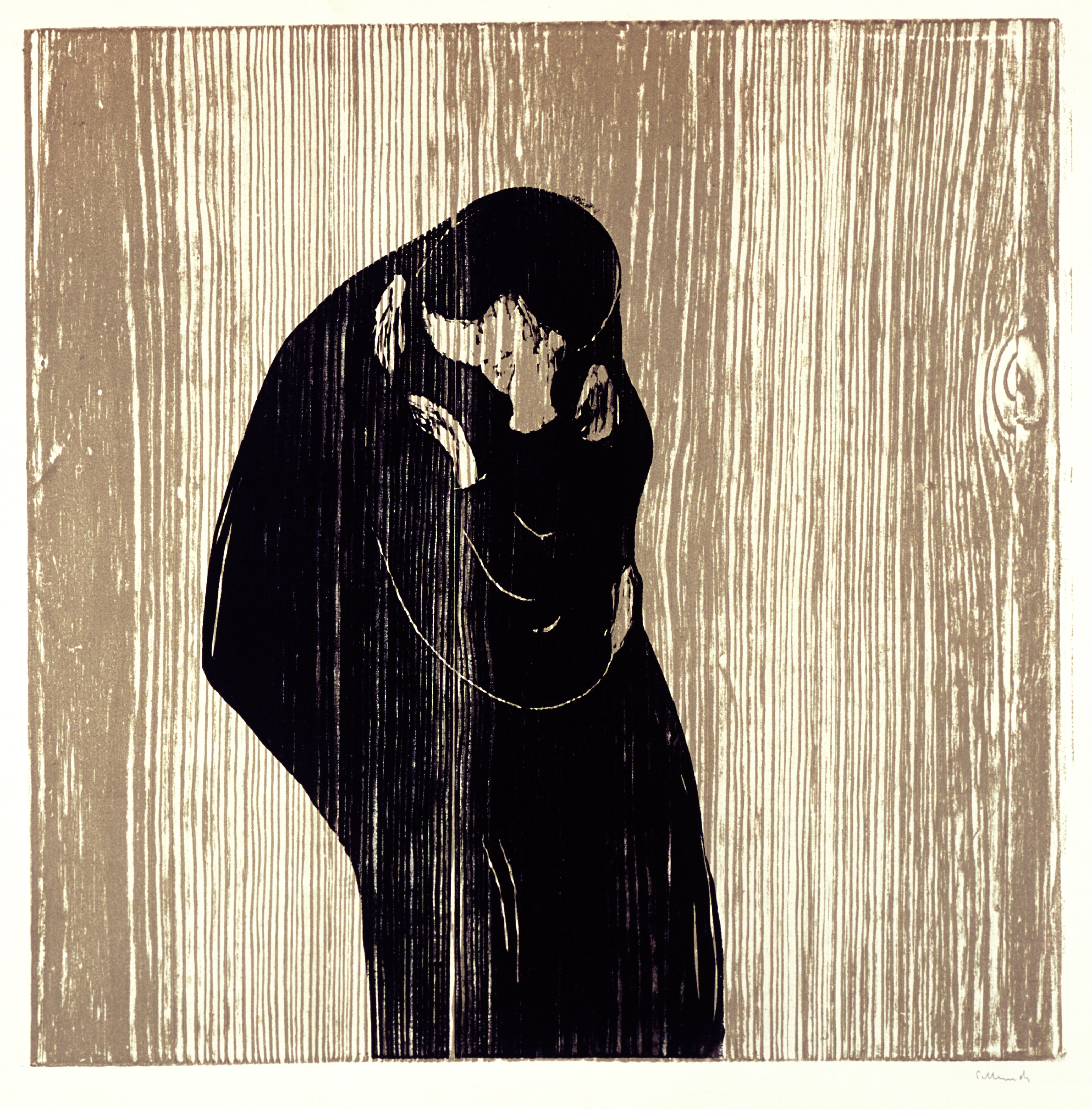

Only the united beat of sex and the heart can create ecstasy.

– Anais Nin, Delta of Venus

[Intro: Adele Givens]

‘Cause you know in the old days

They couldn’t say the shit they wanted to say

They had to fake orgasms and shit

We can tell niggas today:

“Hey, I wanna cum, mothafucka!”

[Chorus: Lil Pump]

You’re such a fuckin’ ho, I love it (I love it)

You’re such a fuckin’ ho, I love it (I love it)

– Kanye West & Lil Pump, ‘I Love It’

What twisted people we are. How simple we seem, or at least pretend to be in front of others, and how twisted we are deep down. How paltry we are and how spectacularly we contort ourselves before our own eyes, and the eyes of others…And all for what? To hide what? To make people believe what?

― Roberto Bolaño, 2666

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

– James Joyce, ‘The Dead’, Dubliners

Edvard Munch, The Dance of Life (1899-1900), [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.