From the weekly cavalcade of comic-book films in cinemas to the US President’s daily Twitter dripfeed, it feels as though American culture is more invasive than ever in Australia. But what lies under the surface of the US’s shiny cinematic facade? In a film market with barely any screen space for indies, American Essentials, organised by Palace Cinemas, weaves new voices and old masters of US cinema into a program to show unseen facets of what can seem like an ubiquitous culture.

“People might think that the USA is this homogenous mass of consumption and communication,” says artistic director Richard Sowada, speaking to Neighbourhood on the phone ahead of the festival’s launch in Sydney next week. “It’s really not. If you look deeper, it’s made up of individuals – people who are committed to uncovering hidden things in American political and emotional states.”

Columbus, by critic and video editor Kogonada, is one such human-scaled drama in the program, and has already been called the work of a new auteur, while Strange Weather is an intimate film about a mother, played by the great Holly Hunter, still coasting on a sharp emotional edge years after her son’s suicide.

“The filmmakers in this program are very happy to be very critical of their own artform and the world that surrounds it,” continues Sowada. “So I didn’t try to hide away from a critical approach, whether it be activism or a stand on who we are, where we’re going and what we’re proud of.”

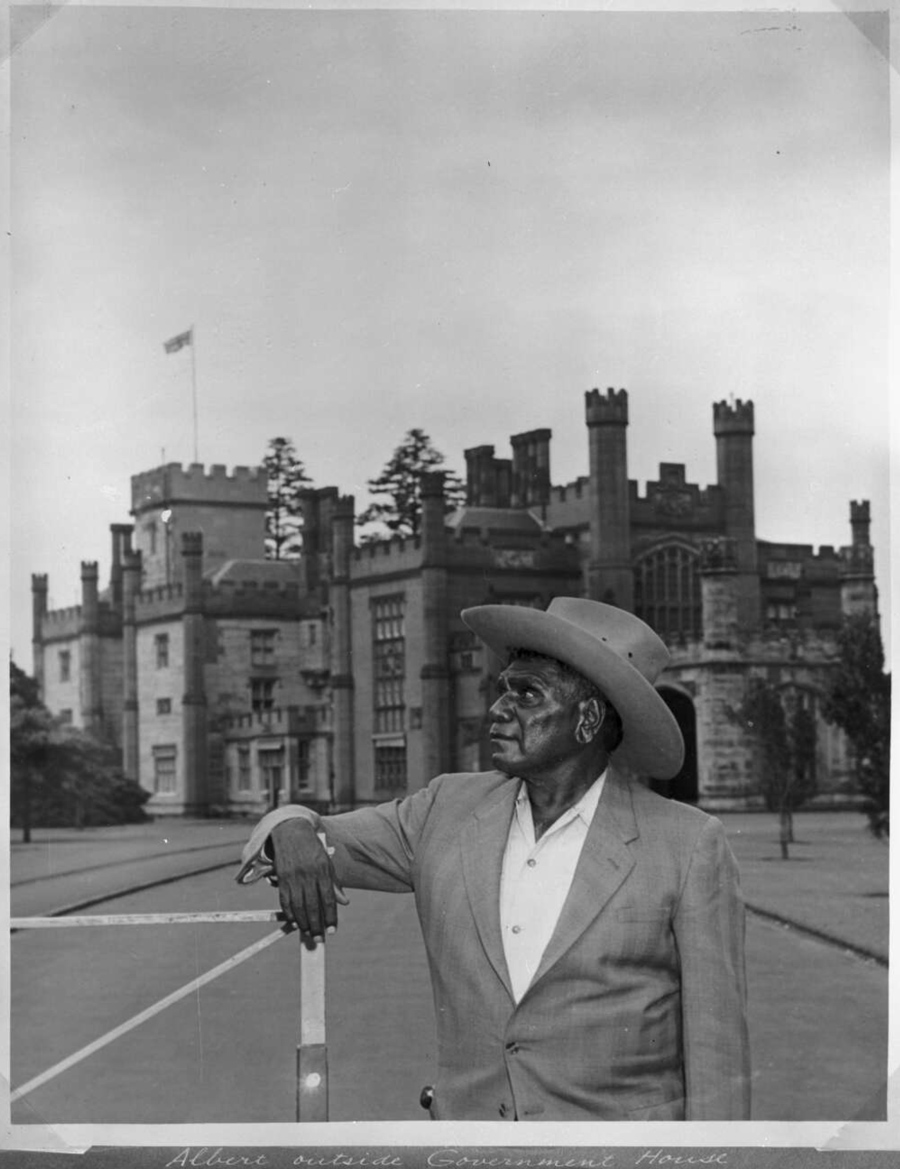

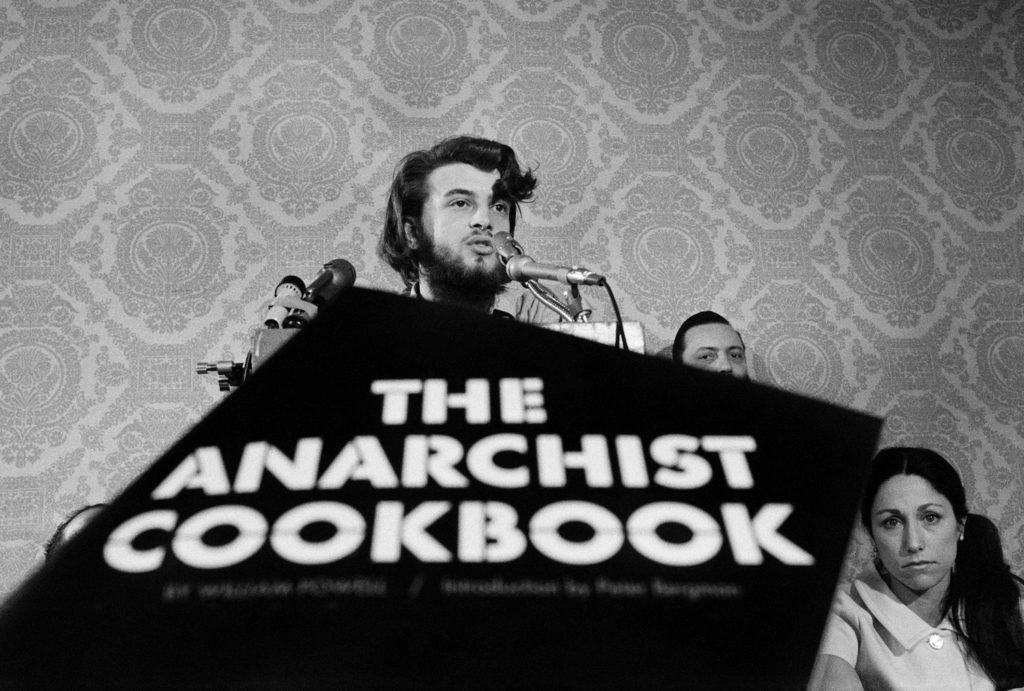

That activist component runs strong in the festival program, as you might expect from a country in such fractious upheaval. “Documentary is very strong at the moment,” says Sowada, who has sourced most of his films from the US festival circuit, including Sundance and True/False festivals. “In this program, we have directly political works. We have one about media control [All Governments Lie], one about an activist bible called American Anarchist, and we have more personal essays, like the Charles Bukowski documentary, which isn’t politically motivated but it’s very community-orientated in that it’s critical of how people relate to each other and to social environments.”

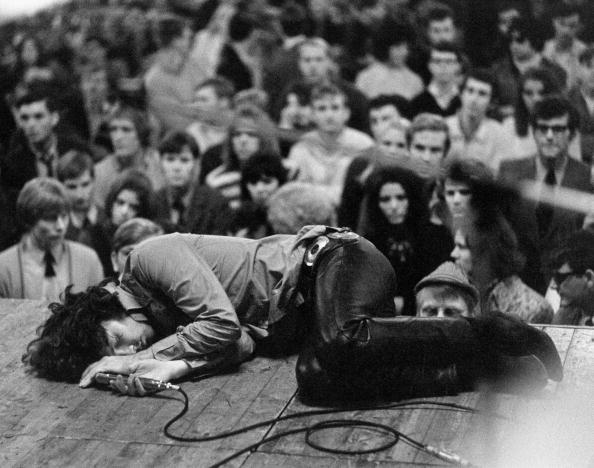

Unearthing what’s hidden beneath the veneer of American normality has been the career-arcing concern of David Lynch, a key figure in any survey of American cinema. Ahead of next month’s launch of season three of the seminal arthouse-noir series, Twin Peaks, American Essentials is screening David Lynch: The Art Life. By Jon Nguyen, Rick Barnes, Olivia Neergaard-Holm, the documentary dives into Lynch’s visual art practice – after attending art school in Philadelphia, the director became preoccupied with how to animate his paintings, eventually turning to cinema.

The documentary, says Sowada, is “more about art than about film. Lynch isn’t just a filmmaker, he’s an artist, thinking about the emotional landscape of how people are thinking and feeling. He doesn’t paint flat canvasses, he paints with things plastered to the canvas. It’s a very three-dimensional approach to art. The doco shows a continuum between art and film: his movies aren’t film or art, they’re film art. The documentary ends where Eraserhead starts, so it shows the movement of his artmaking practice into filmmaking.”

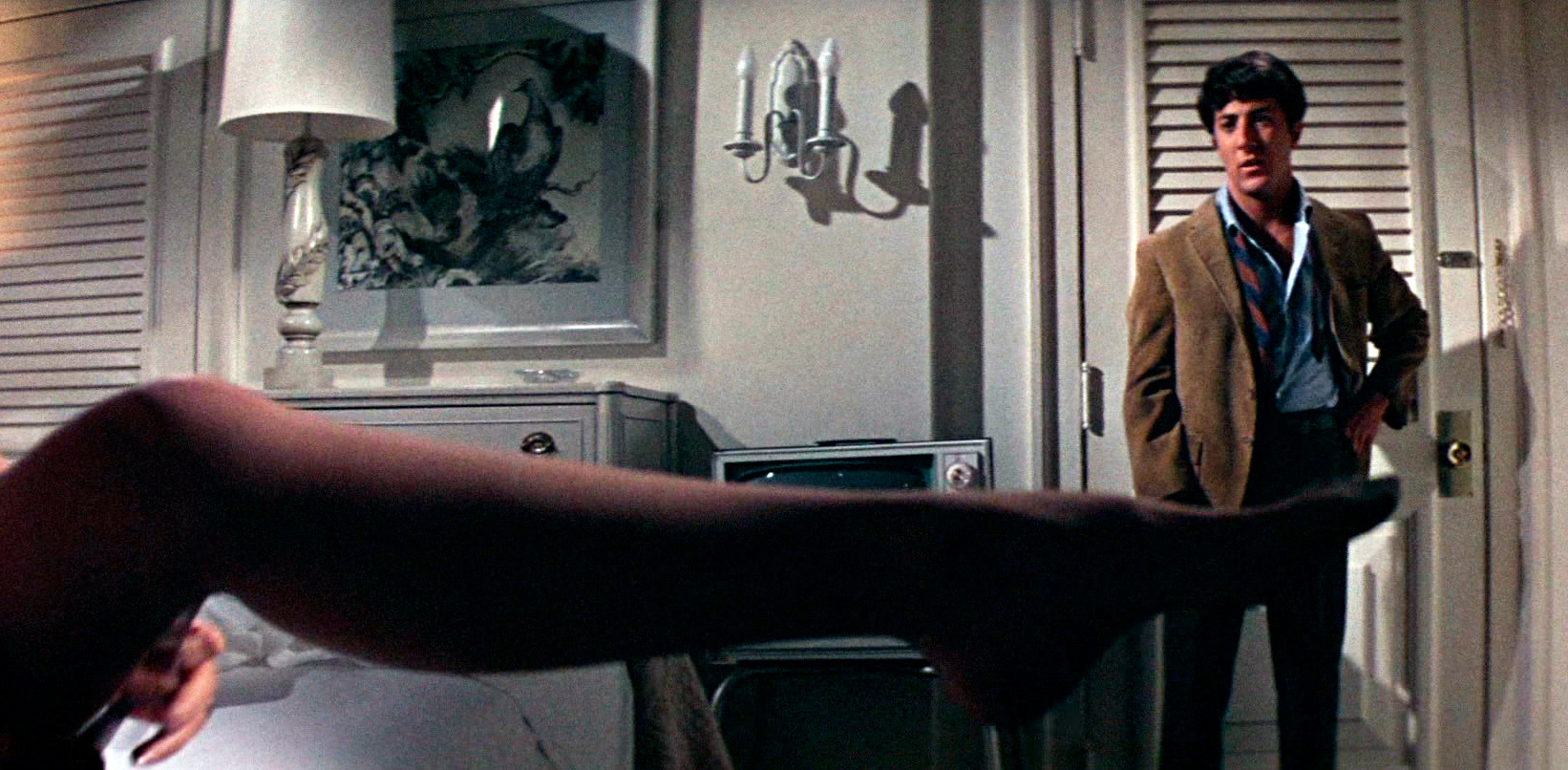

“Someone like Lynch is so commercially successful on big and small screens. To still have such links and commitment to alternative art practice and experimenting actively and deeply within commercial contexts is a very subversive thing.” Bringing that subversiveness to the mainstream and changing mainstream ideas of what commercial cinema constitutes may be the very essence of Lynch’s legacy. In the same vein, Sowada has curated other filmmakers who changed dominant ideas about what cinema can achieve, with newly restored digital prints of classics like Woody Allen’s Annie Hall and Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. Andy Warhol, another artist-filmmaker who played in the hazy zone between moving image art and longform narrative cinema, is also present in the program. Sowada describes Andy Warhol’s Bad as taking on documentary-like qualities in the way it captures the urgency and chaos of New York City in the 1970s: “Aesthetically, it’s right on, today.”

Hollywood’s shift toward a business model of repetition of existing franchises, along with the advent of video-on-demand, has brought with it a reduction of space for small- to medium-budget films in theatres. It’s a shift that Sowada says he thinks has accelerated change in all aspects of cinema exhibition, including festivals and arthouses – even Dendy Newtown now programs the latest Disney live-action remakes and Guardians of the Galaxy installments. “Film festivals are changing. It’s a different industry than it was two years ago, Amazon and Netflix have brought a complete revolution.” That has created an environment where many films that would previously have enjoyed theatrical releases are going straight to DVD and video-on-demand. As a result, the American Essentials program goes far beyond fringe, marginal fare, staking out a patch of cinematic turf for titles that would have enjoyed much wider releases just a few years ago.

“From an industrial point of view, there’s been a drift away from foreign language titles and a lack of trust in interesting films – a growing conservatism in choices by mainstream exhibitors and distributors,” says Sowada. Cinema has found itself at the strange juncture where low-budget US films are as difficult to pitch to commercial exhibitors as foreign-language films. “A couple of the films in the program just couldn’t get broader theatrical distribution – distributors were wavering, saying, ‘we love these films, but they’re not what we’re used to’.” In a world of what Sowada calls “instant results,” the release of slow-burn films is falling away. “How do these films not get a chance to hit it on the commercial circuit? The beauty of putting together the American Essentials program is to reintroduce these films to the big screen.”

From an outsider’s perspective, US culture seems to be splintering towards a more restless, divided, unhappy place that’s rarely shown in multiplex films. But Sowada says that festivals show that “you can harness the big-screen environment to show different approaches. The films are very idiosyncratic and personal with small casts and small budgets, they’re not making grand statements, they’re introspective films about people and the way people are working in the world around them.”

Charlie Siskel’s documentary, ‘American Anarchist’