Award-winning conflict photographer Stephen Dupont has devised an impressive new theatrical experience entitled Don’t Look Away.

Constructed as a monologue, it places Dupont at a table piled high with his journals. Dupont addresses the audience and himself as startling images and film are projected overhead. This makes for an intense, sometimes haunted journey through Dupont’s work in places like Rwanda, the Middle East and Afghanistan.

Don’t Look Away reaches its climax with video footage taken by Dupont as he stumbles around a scene, in shock and bleeding from a head wound, controversially continuing to film in the aftermath of a suicide bombing in which people he was travelling with were injured and killed.

Director David Field (The Combination and Convict) deftly steers Dupont down a confessional storytelling path with far wider implications for the nature of war photography and conflict journalism – and the soul of anyone who ventures down this road.

Use of a video interview with Dupont’s mother serves as centering device as Dupont tries to explain and justify himself to her ghostly presence, even when what she is saying amounts to nothing less than love and faith in him all the way.

As a narrative holding device this can get a little self-conscious, but Dupont’s images (published in places like The New Yorker, The New York Times and Vanity Fair) are overwhelmingly breathtaking – and his quest for an honest line of conversation with us triumphs over dramatic wobbles to leave us with an extremely memorable evening.

NEIGHBOURHOOD interviewed Stephen Dupont, who was at the time working in Dubrovnik, Croatia, via email just a few weeks after a preview of Don’t Look Away in Sydney.

Stephen Dupont. Photograph by Bradley Scott

I have to ask, why do the show? I’m guessing you felt some need to find a story in your life? Or remake one because you had too many?

It had been an idea and concept running around in my head for a while. I am always looking for fresh innovative and immersive ways of showing my photography and sharing my stories. I wanted something different in the way of presenting the photography, I didn’t want it to be a typical keynote or TED talk-esque kind of thing, I wanted something that would be powerful and confronting to an audience. I felt that if I could take the audience on a journey visually and orally that might somehow be driven in such a raw, honest and personal way I would challenge the audience and make them feel something profound. If I was only out to shock, I would show the pictures with music only, but here I am telling my story, my experiences of the events I covered warts and all. I think this enables people to relate to what i have seen and what they are seeing. I’m challenging them to not look away. To even take responsibility to remember and not forget. Because we live now in such a digital social media obsessed world that images and events are flashing by us daily, here is a time to stop and be directly involved in kind of rollercoaster ride through humanity and inhumanity.

I had feeling Spalding Gray’s Swimming to Cambodia was an influence on the performance?

He’s cool, and is an influence of course. But I think the influence is more internal in a weird way; each performance is different depending on my mood, it is real. I’m no actor and I allow myself to be immersed into the stories and then my performance becomes really personal.

How did you connect with David Field as director?

He’s been a good mate for sometime now and I’m a big fan of his acting and directing. For me David is the Harry Dean Stanton of Australia, someone who rarely takes a lead role and never fails to deliver memorable performances. He’s the ultimate vagabond and someone I relate to on a really personal and respectful way. The moment I mentioned the idea to David, he jumped on it, he totally got what I was trying to do. He has a strong activist view of the world and our politics and outlooks are very similar, and he’s bloody funny. I knew I would feel comfortable working with him and I knew that my performance would be so much better with his guidance. He has been instrumental in crafting the script down to prose, which is something I would not of done without his input. And it is the direction from David that has allowed me to be myself, to not try and emote or act, just to be and let it happen.

Your mother very central as figure that you return to and address during the performance to find a kind of moral purpose – but also even beyond death?

I had this kind of strange thing happen when I was looking down at her body in the hospital: it came to me that I had been seeing death my whole life, that I’d been staring down at the dead for a long time. After dealing with her death I then decided that I would pursue a project around the theme of death – and this is how Don’t Look Away was born. In a way, I am going through my own self-healing and dealing with her death. This show has been quite revealing in that way, quite therapeutic. I do feel I am sharing my stories, my photographs and my life, things that I missed out on sharing with her when she was alive. I spent the last 38 years thinking of my dad, he died when I was young; now I’m thinking of my mum.

I liked sequence in Afghanistan with Ahmad Massoud, the Afghan military leader who gave hope to people. That part of performance and your images of him seemed illuminated with hope.

Massoud was a kind of rebel humanitarian in my eyes, but this might appear terribly wrong to those Afghans who suffered under his fist. He was no saint, but as a leader facing first the Russians, then fundamentalist Islamic forces and the Taliban he seemed a better warlord then the rest. My time with him was incredibly memorable as I was given great access and I able to see things he did that for me were profound. He had a presence around him that was so engaging and powerful and for a photographer that was incredible.

Do you worry image-making is finished? Flooded by the citizen iPhone snapper? How do you beat that?

I still feel there is hope and interest in great photography, there are still stories to discover and tell. I think if something is done in a really personal and unique way then photography will keep going. It always comes down the individual storyteller and I think we can use these new technologies as well to push the boundaries of storytelling to exciting levels. There is no escaping the social media right now, but who knows what this will look like in ten or twenty years from now.

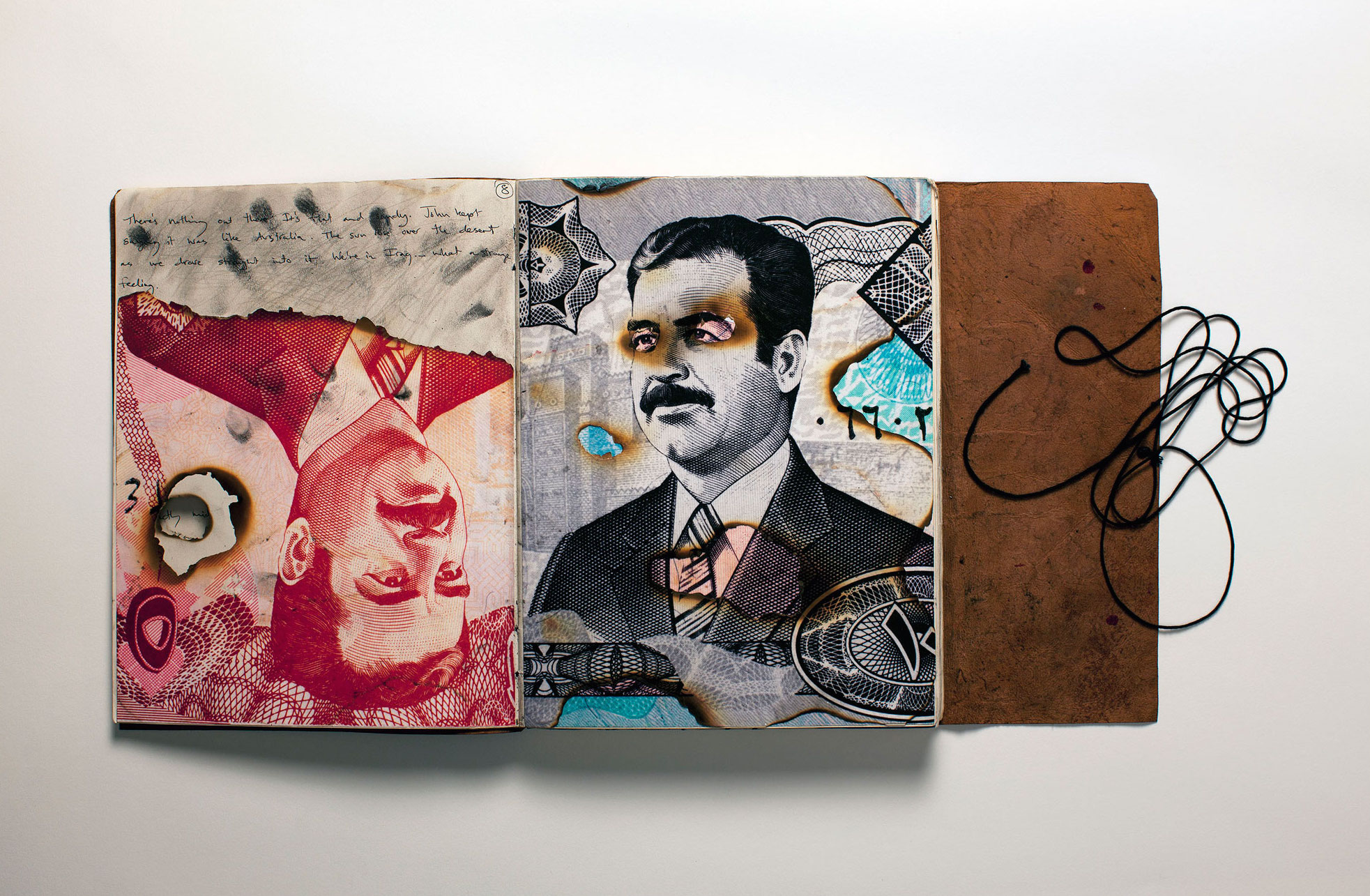

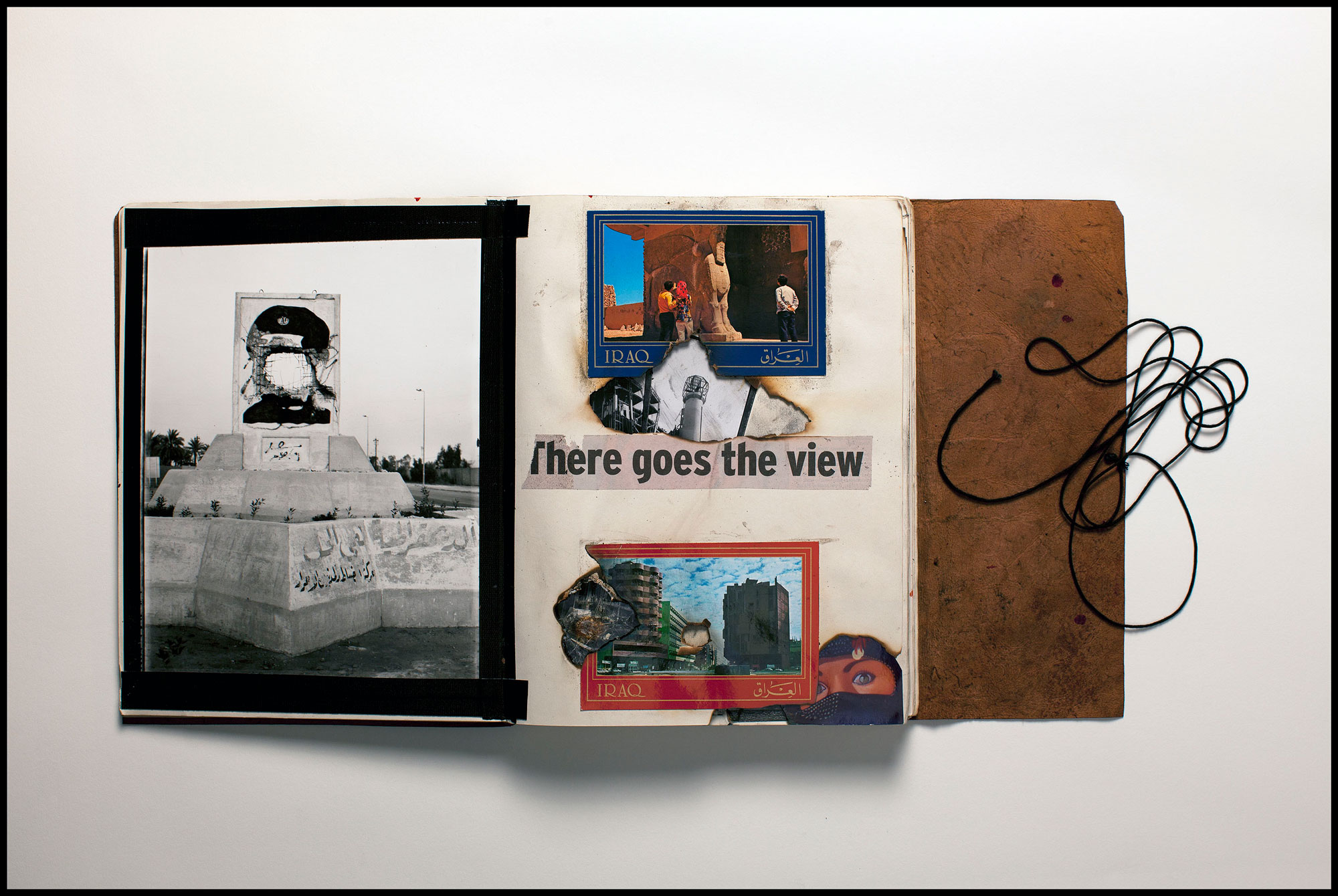

Stephen Dupont’s ‘Baghdad Diaries’

The climax of Don’t Look Away is the video footage in Afghanistan, when you kept filming after the suicide bombing. That earnt you a lot of praise and criticism. It seems like you’re needing to reflect on that moment and ask yourself again, as you do in the footage itself, why am I doing this? Even ‘Why can’t I stop’ Is that hard to watch for you now?

I can look back now and see that I was in shock due to what I had been through… a witness and a victim all in one. I think a mixture of adrenaline, shock and what seemed like clarity at the time drove me to work in a kind of clinical way shooting and then talking to camera. Knowing that I might of been able to help my colleague Paul [Raffaele] better left me feeling some guilt. Yet I know that in my state of mind at the time, I can’t really be blamed for this. If I was not in shock from the blast I would of been in a more rational, normal state of mind to make judgment calls. Yet it’s always an uncomfortable feeling, nonetheless, as you feel you could of done more on reflection. When I see the footage now it just feels so surreal and it always makes me feel just how close Paul and I came to death.

Stephen Dupont’s Don’t Look Away is part of Vivid Sydney. Performances at the MCA on Saturday, 27th May; Tuesday 6th June; Thursday 15th June; Friday 16th June. Show time is 7pm. Go to canon.com.au for details.