At some point people started referring to Shigeru Ban as the “good” architect. Other architects, it was assumed, were not good but bad, or worse, celebrities.

Like many forms of creative struggle after the first recession of the 21

Shigeru Ban, a Pritzker Prize laureate, is certainly critical when it comes to fellow architects. Utilising the platform of choice for those interested in revolutionary change, he vocalised his dissatisfaction with the architectural elite at a TED Talk in 2013: “I was very disappointed at my profession as an architect, because we are not helping, we are not working for society, but we are working for privileged people, rich people, government, developers. They have money and power. Those are invisible. So they hire us to visualize their power and money by making monumental architecture.”

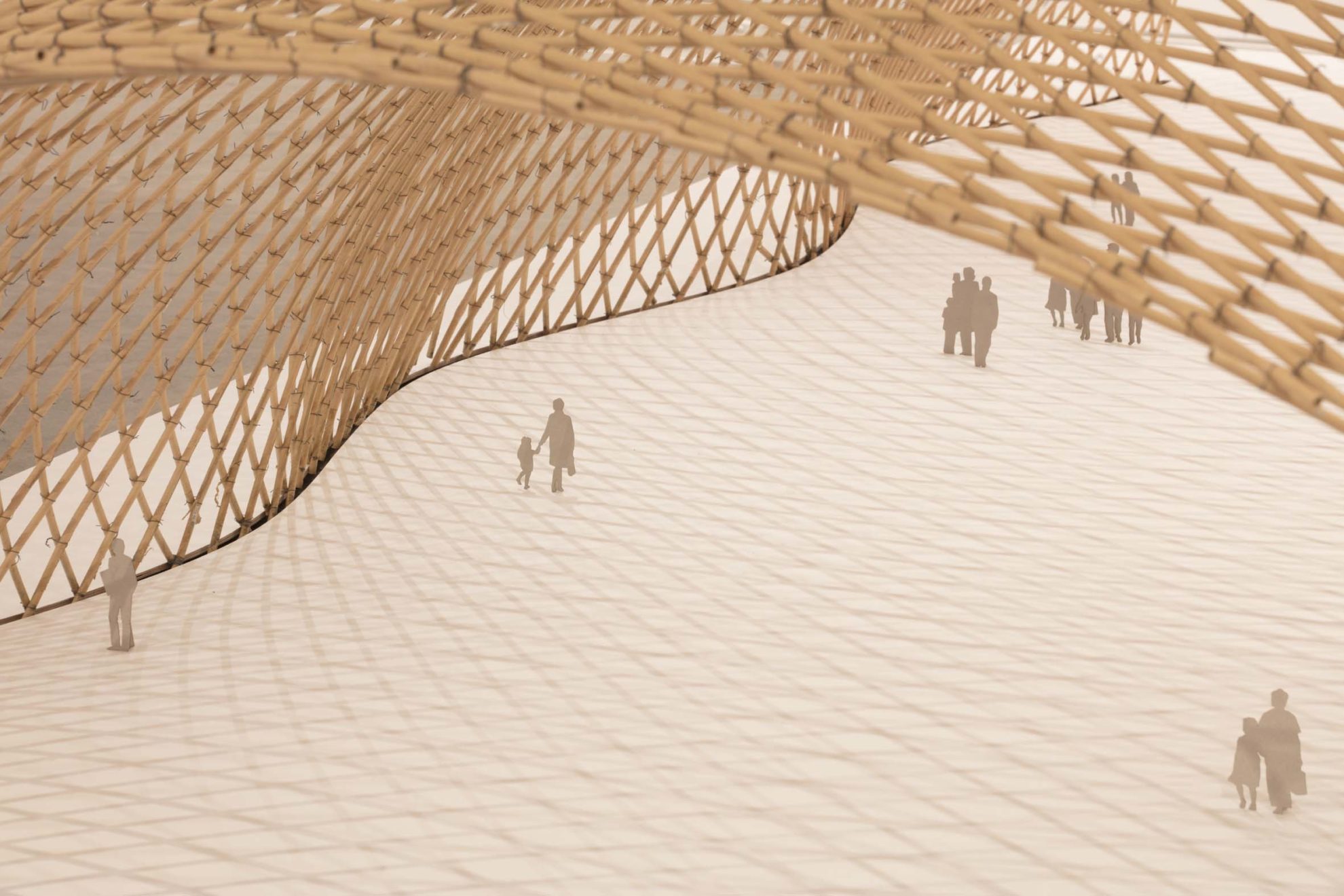

Shigeru Ban, SCAF, March 2017, Photography by Brett Boardman

Decades before architecture’s social and political conscience reawoke, Ban turned his mind to humanitarian projects in disaster zones. In the totally unregulated space left by environmental crises he experimented with novel materials – beer crates, recompacted rubble and his trademark paper tubes – to construct relief shelters for the victims of natural disasters.

As part of The Inventive Work of Shigeru Ban, the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) has erected two of Ban’s temporary shelters, the ‘Paper Log House’, developed following the Kobe, Japan earthquake in 1995, and a shelter conceived last year after the 7.9 magnitude earthquake in Ecuador.

What drives Ban into disaster zones is a jumble of things – a desire to help, a fascination with weakness and scarcity and a healthy dose of self-promotion. The press crown Ban’s humanitarian achievements with the same unreflective aura as his caption, a descriptor he no doubt rejects. “Good” is a mystifying word to describe Ban, whose ethics are reclusive.

Looking for the source of Ban’s inspiration, he claims, “there’s no difference between commissioned work and disaster areas. The only difference is I’m not paid, otherwise it’s the same.”

Trying to resolve Ban’s professional conscience is its own reconstructive effort. There is a sense of the economical to everything he touches and he often reiterates his hatred of waste in public talks and interviews.

“I started to reuse and recycle material in 1986, before people started talking about environmental issues,” Ban told the Australian Financial Review in March. “I hate to waste.”

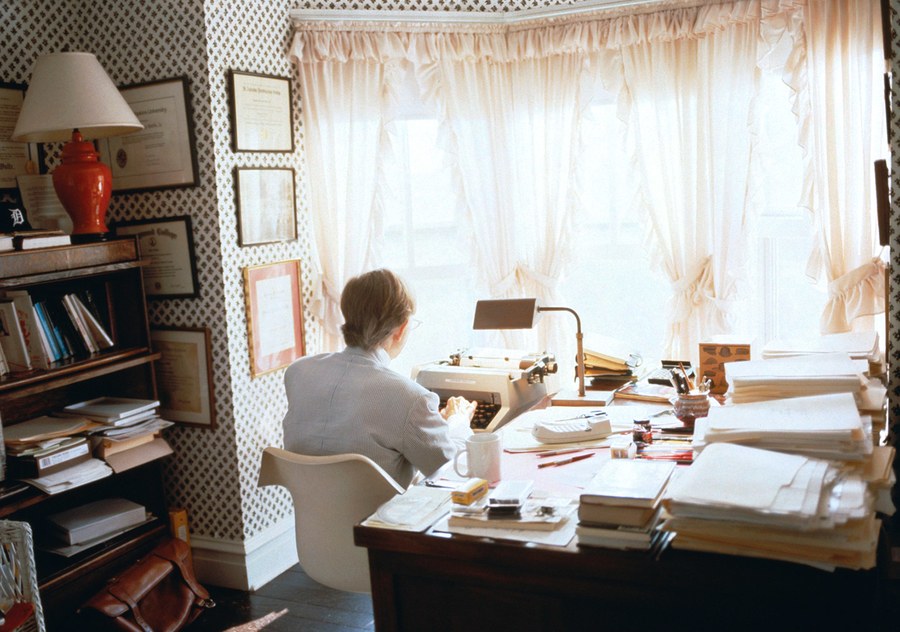

But titles like ‘green architect’ or ‘environmentalist’ he firmly rejects. These phrases long post-date Ban’s period of critical learning in the late 1970s and early 1980s at the radical SCI-Arc school in Los Angeles and, later, The Cooper Union in New York, where students recited poetry and digested a pure and potent modernism under the deanship of John Hejduk. Hejduk, more artist and theorist than architect, was more likely to find a solution in a painting than a building.

Less idealistic than his US teachers, Ban’s subjectivity is equally out of place with the burdensome codes of contemporary sustainability and eco-friendly design, with their precious performance standards goading the artist into compliance. Ban’s material modesty and ideological conservatism prioritises common sense and individual style.

“I like the architect who invents their own material or structural system, because I hate it,” Ban attests, “I hate to be influenced by fashionable times of the day.”

When everything that is not Shigeru Ban is pushed aside there is left beauty, comfort and utility. “I cannot design something not beautiful,” says Ban, fatefully. “Even for the humanitarian project, it has to be beautiful and it has to be comfortable. As well as the commissioned work – it’s the same.”

Shigeru Ban, SCAF, March 2017, Photography by Brett Boardman

Ban dreams the dream of modernism with delicious ease. When he refuses to distinguish the humanitarian work from the commercial work of Shigeru Ban Architects (SBA), the disaster relief projects seem to shrug off any pretence of activism. He casts the work of an architect as purely technical and corresponding to the same unalloyed source of inspiration. “As long as the architect is designing, it has to be beautiful and comfortable,” says Ban.

In an age where developers rule the cities this statement of equivalence might be painfully true, but for other reasons. The few itinerant name-brands of architecture brought in to activate commercial precincts with prestige get the biggest tranche of cash and creative freedom. This they squander on “decorative, funny shapes,” he admonishes. “Nobody wants to be innovative and experimental, nor to be sued.”

By this questionable assessment, other practitioners keen to innovate need to hurl themselves into a disaster zone to win back artistic fiat by sweat or dwell upon the sanctity of a blank canvas. The ultimate privilege, Ban can have it all.

Despite his unease towards expensive monuments, Ban is most effective at his most monumental and least effective at his most utilitarian. The apogee of Ban’s disaster relief projects may have been the temporary and monumental ‘Cardboard Cathedral,’ constructed in the aftermath of the 2011 Christchurch earthquake for the Anglican faithful. The NZ$7 million structure used 98 truck-length cardboard tubes to perfectly envelop the ghost of the neo-Gothic original. Extravagantly conceived, Cardboard Cathedral displays the careful majesty of Ban’s art – a unique use of materials, structural complexity, openness, outwardness and directness.

Disaster relief, as practiced by Ban, is a series of small-scale deployments with modest outcomes in number, no less important for the many communities served. Twenty-one temporary shelters and a church in Kobe. Seventeen in Turkey. Twenty in India. Forty-five in Sri Lanka. Nine classrooms and a nursery in China. A shipping-container complex in Tohoku for a hundred and eighty-nine families. A classroom in Nepal for three hundred students. Twenty temporary shelters in Ecuador. A community space in Kumamoto. Unrelenting,

In 2014, his contributions were recognised and he was awarded the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s biggest. Australian architect Glenn Murcutt joined other jury members in citing his humanitarian work in their praise. The same year Ban had his first US retrospective at the newly opened Aspen Art Museum (AAM), a US $45 million building SBA designed.

AAM CEO and director, Heidi Zuckerman Jacobson, initiated a 24-hour gala to celebrate the opening, which included a rooftop ‘silent disco,’ dream readings, morning yoga, food tasting and, among other inaugural exhibitions, Shigeru Ban: Humanitarian Architecture. In a place like Aspen the complementary nature of philanthropy and opulence is never far from curdling, left unagitated.

A similar funk pervades the polished white stone courtyard at Sherman-SCAF in Paddington, where the two shelters idle in a zenlike state of zero-thought. On closer inspection, the hundreds of paper tubes assembled here have been covered in a polyurethane resin and, unless repurposed by the Shermans, are likely unrecyclable. Though strictly replicas, the cost of the two disaster shelters on exhibition at SCAF is rumoured to be in the tens of thousands per unit. In context, it verges on hypocrisy, but only just.

Privilege and charity are parasitic and it would be unfair to indulge in the iconoclastic disregard of Ban’s brilliant and protean approach to humanitarian building projects. Someone will take the tubes.

Reflecting on the nexus of his commercial and humanitarian success, Ban says, “Now I have bigger commissions, and also those projects help me to work on the pro bono-based projects, and also because, with privileged people, they become my donors for my pro bono projects.” It is a glib and manageable irony that a few of those donors are probably eyeing off a shelter for their next cocktail party, even though it might not be in the spirit of the work.

Architecture itself has moved on since Ban trudged into his first disaster zone with his tubes to bring some joy and fascination, and a little help, to the devastation left by a force majeure. “It’s important to have a gathering space after a disaster,” Ban reflects, whose paper shelters are more than just shelters. They’re personal statements.

In the wake of disaster, Ban found a material that performs because of – not in spite of – its structural weakness and poetically applied it to the subject of human resilience. His preoccupation with how limitations engender powerful creative responses is the common thread between him and the next generation of socially concerned architects. The difference is that, for Ban, the response occurs in relation to material and environmental constraints and never political or economic ones. Ban-san is just “good.”

The Inventive Work of Shigeru Ban is at Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) in Paddington until July 1. The show concludes the Foundation’s decade-long program.