At 6am I’m half-asleep when we assemble at Toxic Yoga, our regular meeting place. It’s the overpass opposite the Coke sign that crosses William Street. We’d once brainstormed potential uses for this overly wide and under-utilised land bridge. Outdoor yoga sessions were one suggestion. The high-level car fumes make it toxic but perhaps that could be a thing, like hot yoga. Needless to say the yoga never happened but the name stuck.

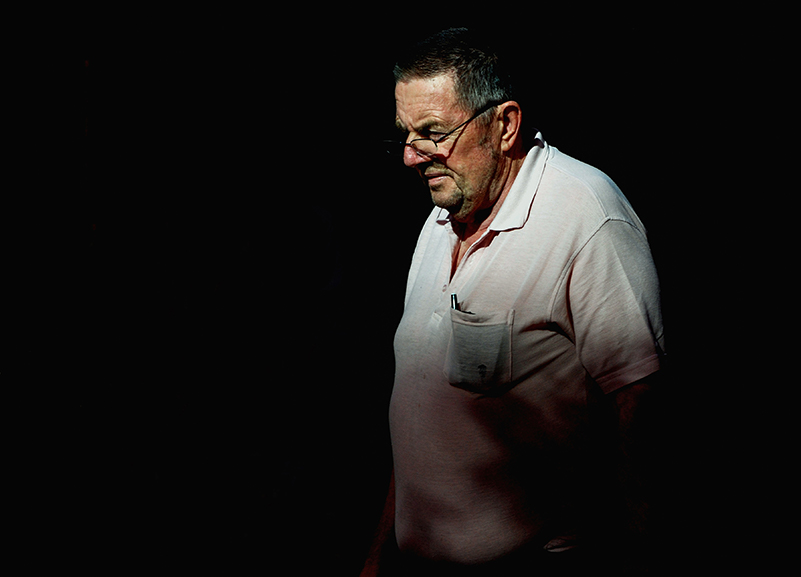

Today, Shawn’s t-shirt reads, ‘I Knit’ and shows an unravelling ball of wool. His daughter made it as a proclamation of his hobby and he wears it proudly. Rubber strips peel away from the soles of his orange running shoes. He’s fit these days, almost muscular, daily exercise having replaced his former beer drinking passion. Neither short nor tall, his thick body is clothed in random garments that form his running attire. Born to a Chinese-Malaysian father and Queensland mother, he describes his appearance as a mature Ronny Chieng: International Student.

Shawn scratches his shaved head and we go through the motions of our awkward greeting. We haven’t resolved a satisfactory solution, not quite shaking hands, not quite nodding. I’d once tried a shoulder pat but we both regretted that. So instead this morning I tell him about the dream my alarm interrupted 15 minutes ago, a Star Wars battle scene,

“Blasters or Light Sabres?” he asks.

We do a quick inventory of injuries: his foot, my hip, his knee and then we start. The first block is run mostly in silence except for the jangle of his watch, a clunky old analogue with a loose metallic strap. There have been a few watches recently: the Casio digital model circa 1983 and before that he’d trialled an Apple watch which hadn’t lasted long.

“It’s actually bloody useless,” he explained.

“What’s with you and watches?” I asked.

“I like to know what time it is.”

Running down William Street is the hazardous part of the run while we’re sleepy and it’s dark. I’m wondering why I’d had a Star Wars dream let alone shared it. Building speed downhill we’re forced to stop and start at the many intersections. Dodging drunks, street-cleaners and trannies we’ve been propositioned, threatened, chased and almost run over by cars running early morning red lights. While we wait for each green man we’re adjusting shoelaces and stretching calves. Shawn’s calves are enormous, a legacy of eschewing car-ownership for cycling.

By Cook and Phillip Park at the bottom of the hill we’re safe. It’s unlit and Shawn steps on the loose manhole cover, which clanks in the dark and shocks us every time but there are no more cars. We dodge the bin-feeding ibis and the homeless people and then on past the Cathedral school up the hill: No-Talky Hill. No-Talky Hill is our first incline, from the Domain car park entrance up to Art Gallery Road. The legs start straining, the first puffing kicks in and conversations drops.

When I first met Shawn Seet in 2005 he was making his name as a TV director in commercial TV police dramas having started in the edit room. Our kids were at preschool together and he and his partner Sarah lived nearby. Canal Road wasn’t the best show going but it gave him a profile and anyway, I was impressed. He’d made All Saints and The Secret Life of Us and, knowing nothing of the TV industry I was interested. He seemed quiet and reserved but when he answered (almost) everything correctly at school trivia night people noticed. His big break came when chosen to direct Underbelly for Channel 9 on primetime TV. At home we cheered as his name appeared on the credits and we gave him glowing reviews the day after. The show’s regular sex scenes became a talking point on our runs. When he recounted a particular scene where he’d demonstrated a Reverse Cowgirl to the two actors I was hooked.

At the top of No-Talky it’s on past the Art Gallery and down into the Botanic Gardens. We’re striding out now, hitting a good pace. When overtaken we comment on the other runners: too young or showing off, and we mock their vigorous running style.

The pathway around Farm Cove is blocked by security and fencing protecting yet another of Sydney’s outdoor events. But this is forgotten as the early sun lights the city facades and we look across the harbour to the Bridge and the Opera House. Then it’s on to Mrs Macquarie’s Chair and the halfway point of our run. After a sharp incline to the Chair we’re looking east towards the Heads with the meditators, photographers and tourists who share the sunrise. We’re puffing hard as we round the point and it feels like we’re heading for home.

I’d been running the same five-kilometre circuit on my own forever. When Shawn asked if he could join me it felt weird, strangely intimate, like a man-date. We made a standing arrangement to run each Wednesday but sometimes he wouldn’t turn up after a late night session. Sometimes he just forgot. I presumed it wouldn’t last, that he didn’t show the commitment. I’d send a reminder text on Tuesday nights to confirm and he told me I didn’t need to, that it was a standing arrangement. I felt I’d broken some bro’ code in mentioning it. He was a lot less fit in those days. The years of being the last man standing at whatever party going had started to impact and when he first came running he took a lot of strategic walking breaks.

After his fiftieth birthday, Shawn increased his fitness regime with cycling and swimming on the non-running days. While away for work he’d run on location: along Broadbeach on the Gold Coast for The Hiding and, when filming in Melbourne he’d run along the bay at St Kilda. I’d always enjoyed our conversations but recently our chats darkened to topics of ageing and mortality as his list of ailments grew. Then, to the amazement of everyone, he stopped drinking.

Garden Island, Sydney Harbour, circa 1910-1928. Wikipedia Commons.

Along the eastern side of Mrs Macquarie’s Chair we look across to the Garden Island naval base. On dark wet mornings the sodium floodlights spill light on the empty concrete concourse, its warehouses standing silent witness to the quiet drizzle. Talk turns to Nordic-noir and The Bridge. We imagine trussed bodies in abandoned lorries beyond. Shawn launches his monologue on Scandinavian crime shows being the epitome of current television. I run on, thinking about my own struggle to follow the interwoven plotlines and extensive character lists.

Running past Boy Charlton pool he suggests integrating a quick swim as part of the run. It’s a level of semi-nudity I’m not ready to share and we keep going. Then it’s down the stairs into Woolloomooloo and round past the Finger Wharf. A sculpture series is installed along the boardwalk and we’ve critiqued the selection: a range of life-sized human figures with rabbit or dogs’ heads: it’s a dog’s life. Paparazzi dogs with cameras: news hounds. Dogs on surfboards: surf dog. We fantasise about throwing the art works into the bay: dog-gone.

As we pass Harry’s Café de Wheels the van’s remnant pie stench hits us and I reflect on my failed attempts at vegetarianism. At the McElhone Stairway from Woolloomooloo up to Victoria Street it’s a massive rise and we take the stairs two at a time. Gasping for breath at the top we pause to admire the city skyline. Shawn filmed a scene from Underbelly here a few years ago and I’d scanned the background to make sure the cityscape was chronologically correct: that the right buildings were in the background for the year. It matched my pedantry in giving feedback on The Hiding. I’d advised him that the main character had been on the wrong side of City Road to catch a bus from Sydney Uni to the safe home in Petersham. He hadn’t been impressed.

We walk up Victoria Street to the first driveway. There are a few dog walkers around now, staring at phones while their dogs crap free: dog-shit. Sarah’s Awkward Dog Photo series was a 2016 Facebook highlight. Shawn, never a dog-lover, was photographed in a number of friend’s homes holding their respective canines in a variety of clumsy positions captured just as the dog was successfully squirming out of Shawn’s arms watched by his anxious face.

The first driveway crossing is our cue to start running again on the home stretch. The speed increases up Victoria Street as we dodge pedestrians and coffee crawlers. We’re side-by-side and I’m not sure if we’re competing but the pace is increasing. Sailors are walking down to Garden Island from the station and I leave the footpath for the road to avoid them and gain a slight lead before arriving once more back at Toxic Yoga.

In 2015, when Shawn was nominated as Best Director at the AACTAs for The Code, we tried to tune in. He’d talked-up his newly purchased suit and we didn’t want to miss that image. Sarah was sending Facebook updates from the ceremony while we tried to spot him in the audience on TV. Her updates weren’t synching with the shots we saw on TV and we gathered it had been delayed. There’s a break, and then a simple message, “Shawn Seet!” with a photo of the statue award.

Shawn’s become increasingly obsessed with exercise and now runs on days I can’t make it. The passion he once found for Asahi is being poured into his morning ritual. Although every plate of food still gets doused with salt he wants to do longer and longer runs. We talk about Murakami’s obsessive running habits: 9.6 kilometres a day, 6 days a week.

“Well he didn’t have to get the kids to school on time,” I say.

Our runs start to vary and increase. We cross the Bridge to Kirribilli and back. The harbour is stunning but the ten-kilometre length is a full-Murakami and I need a recovery lie-down afterwards. He suggests running more days each week but I’m not sure I can keep up. I wish he’d start drinking again and pull back on the exercise but he seems obsessed.

In June 2016 Shawn takes a family holiday in Victoria for a few weeks. At last I can stay in bed on cold mornings. It’s a winter break from his Kurosawa master classes and the explanations on why Linux is a superior computer operating system and how to solve D.A.’s cryptic crossword on Fridays and why Proust can write a whole book where nothing happens. A reprieve from the guilt I feel for having not yet watched every episode of House Of Cards or True Detective that he gave me on USB.

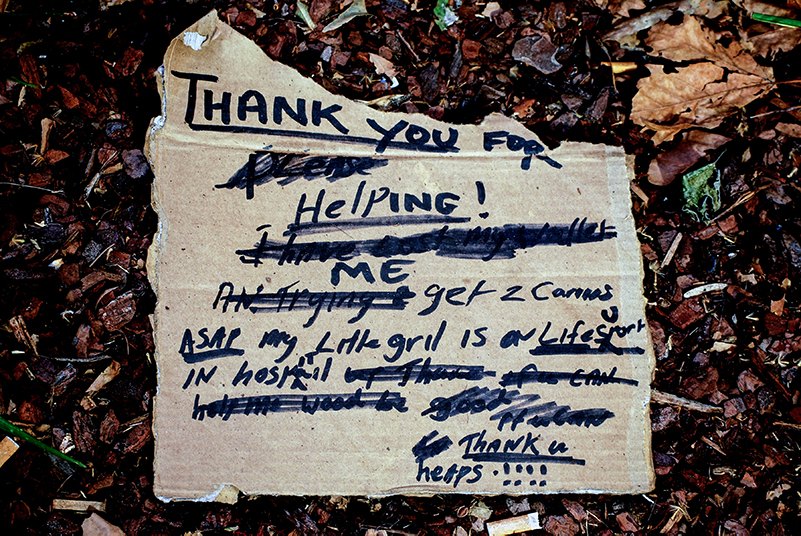

Life slows down in this winter recess and I leave the running for a while. A week later, on a Saturday morning I’m kicking the footy with the kids when a text arrives from Sarah (unusual) in Melbourne.

“Your running buddy will be out of action for a while. He’s ok, but in hospital for a week. He had a heart attack yesterday.”

Oh my God. The words go blurry on the screen. I read again to double-check. I text back messages of support and seek information but nothing returns. I’m desperate for news but there’s no one to contact, no more updates.

Finally on Sunday a photo arrives by text from Sarah. There’s Shawn tucked up in a hospital bed eating a bowl of yoghurt, machines and tubes everywhere. Definitely pale but, ever the director, it’s a composed image. He’s studying a Health Department booklet, You and Your Heart, with an earnest expression on. The glasses perched on his nose make him look like Homer reading something serious and I know he’s going to be ok.

Details emerge: he’d been hard-core swimming in the hotel pool; pumped after learning the BBC had bought the UK broadcast rights to Deep Water. Chest pains started and continued through breakfast. Initially he’d ignored them but the family insisted he went to the hospital to get checked out. Fortunately St Vincent’s was just across the road. From there they’d gone the full banana, rushed him off, put a stent in and told him how lucky he was. Apparently it had been that close.

A week later Shawn returned home and lay low, leaving the house only for doctor’s appointments. I don’t see him but we exchange texts. Shawn sends emojis of pills and ambulances and the one that looks like a smiling mound of shit. It’s a world away from the little pictures of running figures and glasses of beer and confused smiley faces that we used to swap. I go running alone and think about how life moves on, eras end and people die. My grandmother had gone the year before and that still weighed on my mind.

Then just over a month later he texts that he’s ready to join me, but walking only. It feels like a John Howard media call but I’m delighted that he can do even that.

“No green and gold tracksuit?” I ask as we assemble at Toxic Yoga for the reunion tour.

He’s thinner and nervous. So am I. We walk slowly, self-consciously and he reassures me he’s got a special resuscitator and phone in his pocket. I wished I’d done a St John’s First Aid course at some time and can’t quite shake the mental image of having to give him mouth-to-mouth if push comes to shove. Shawn talks about his medication and his cardiologist and his rehab class. We are both looking into the grim future. But we walk on doing a shorter circuit in the same time. It’s incident free and a relief for us both to finish the course safely. At Tropicana where we’d always shared a ham and cheese omelette after the run he’s now ordering porridge and lining up tablets, explaining the various dosages in milligrams. He offers a spoonful of porridge but I decline and look away.

The weeks roll by and, with doctor approval Shawn starts some gentle cycling while preparing for his next show. Preparation includes, as for all his shows, the purchase of five identical shirts. He explains that this eliminates one anxiety, the decision of what to wear each morning as he dresses before shooting.

“Apparently Einstein did the same,” he says.

After a month of walking he starts running again, very slowly at first but it’s a breakthrough.

Sydney Harbour. 2018. Photography by Benjamin Giles.

Shawn’s latest show is a big one, the feature film remake of Storm Boy.

“You don’t want to stuff this one up,” I say, helpful as ever.

“No, this will either make or break my career,” Shawn says, looking past me into the distance. “I’m pretty worried about it actually.”

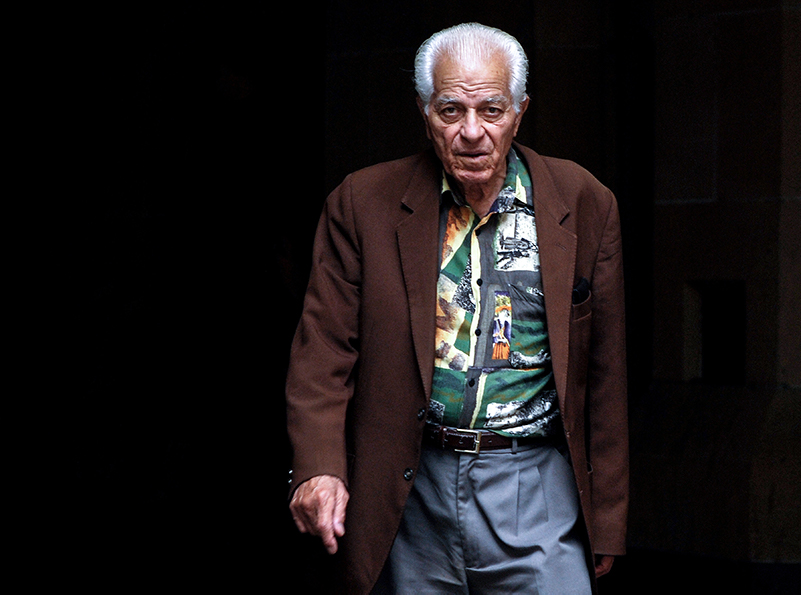

He’s travelling to South Australia scoping the Coorong for locations and having ‘meetings’ with film people. Five pelicans are put aside in a Queensland sanctuary, being groomed to become the chosen Mr Percival. Nationwide auditions are being held to cast the Boy. He visits Geoffrey Rush at home in Melbourne for some script development and I’m keen to hear details but wary of sounding desperate.

“So, um, what’s his house like?” I say, trying to sound nonchalant.

“I saw the BAFTAS on his mantelpiece but couldn’t see the Oscar. Perhaps that’s in a special place,” he says.

The film’s to be made entirely in South Australia: pre-production, shooting and post-production, so he’ll be away in Adelaide for six months. We increase the running frequency before he goes but he’s struggling with a sore foot.

“I was jumping in to the ocean pool at Thirroul over Easter and it looked like the deep end but it was actually curved so I landed hard on my foot,” Shawn explains.

“Are you going to see a doctor and get it x-rayed?”

“No, what’s the point. They’ll only tell me to stop running.”

Storm Boy, directed by Shawn Seet, will be released in January 2019.