Franklin Foer knows what it’s like on the coal face of journalism’s struggle with Big Tech. Formerly the editor of the small-but-prestigious New Republic magazine from 2006 to 2010, he was invited back to the helm in 2012 after the publication was bought by Chris Hughes, Mark Zuckerberg’s roommate at Harvard and one of Facebook’s founding employees.

Since 1914, New Republic had been an institution for liberal thinking and political analysis – the authoritative sceptical voice between Republican and Democrat ideologies. Hughes was just 28 years old, a booster for Barack Obama and a UN advocate for HIV prevention. Foer was charmed, even “exhilarated”, by the changes Hughes promised and the fresh generational idealism he brought to New Republic as a media institution.

Two worlds collided, and – after a honeymoon period that lasted two years – the acrimony began. Hughes wanted to reinvent the New Republic as a “vertically integrated digital-media company”, Foer resisted, and the guy paying the bills won the fight. Foer was forced out, and two-thirds of his staff quit with him.

As Foer wrote later in the Atlantic (where he is now a staff writer), “The bust-up received its fair share of attention and then the story faded – a bump on Silicon Valley’s route to engulfing journalism.”

In his latest book, World Without Mind, Foer widens his argument: Silicon Valley is not only engulfing journalism, he writes, but fundamentally changing the way we think. In the same way that the Industrial Revolution automated physical processes in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Digital Revolution is attempting to automate our mental processes today, and to replace the art of quiet contemplation with notifications and algorithms.

So far the tech giants are winning this war on our minds: so we’d better wake up and start thinking, Foer argues, before we no longer can.

Franklin Foer

NBHD: Hey Frank, is now a good time to speak?

FOER: Yeah, I’m actually driving to rural Virginia to this elite evangelical college, and I’m debating this libertarian guy about Big Tech. I love these debates, they’re so much fun. It’s also like a wild-card audience. Being able to try and persuade cultural conservatives that this is something they should care about… I love the challenge of trying to bend them around.

You’d think that culturally conservative people would be into your message of slow contemplation, trust in institutions… or have I got the U.S. wrong?

You’ve got the U.S. wrong. I’m sure this is like a place that went, you know, 70, 80 per cent for Donald Trump.

Before we start talking too much about Big Tech, your book is, in part, about quiet contemplation and a love of reading. Do you remember the first book you ever had?

The first book I ever had as a child… my uncle gave me his set of encyclopedias from the 1960s, and they were done by this television personality called Art Linkletter. And they were kind of absurdly popularised, with all sorts of information, and very colourful… which is kind of the pre-digital internet, right? It was just such a good thing to get lost in that trove of knowledge and to have that sense of mastery, but also just the endless surprise that comes with the discovery of each new entry. And to me that was the greatest – the Platonic reading experience.

And do you remember when you first decided that you wanted to work with books? That you wanted to become a writer?

When I was at university I dreamed of becoming a historian. And I discovered journalism, which was academia through less crazy, esoteric means. Journalism as a profession is really such an incredible privilege – to be able to be kind of an amateur expert, who’s constantly shifting from subject to subject. I mean, it’s a bit like reading the encyclopedia, where you never get stuck on one entry for too long, there’s always a surprising next entry to be found.

When did you get serious about writing and journalism?

My senior year of university I interned at a now-defunct magazine called Lingua Franca… a bit of a legendary magazine that was actually about universities, but it had a real mischievous, witty way of writing about them, where they did this puncturing of a lot of the pomposity, and writing about the sacred characters in the university as if they were celebrities. There were quite a few New Yorker writers who started there, it was really an exhilarating place, and short-lived, so it lends itself to mythological treatment.

My editor here is a big fan of your first book, How Soccer Explains the World, about the connection between soccer and globalisation. How it was that you came to bring those two topics together?

As a political nerd I couldn’t help but find part of the thrill of soccer to be the fact that it was rife with politics and geopolitics, and that rivalries had this added dimension of carrying histories of imperialism and war, and that was part of the reason why the game was so authentically intense. I always actually viewed the game through a somewhat political lens. I was a terrible soccer player as a child, so I did what nerdy kids do – which is, you set out to master intellectually the things that you fail at physically.

Who’s your team now?

Arsenal is the team I’m most devoted to, which is a source of constant pain.

A lot of your new book World Without Mind deals with your experience at the New Republic. At the start you say that you’re writing was fuelled by a certain amount of anger, and I want to know: was that anger directed at Chris Hughes or at the C.E.O. [Guy Vidra] or more towards the general crisis of the media at the moment?

I actually don’t have any real anger to any of the individuals that I know in particular. My anger is more directed at Facebook and Google and Amazon, because all these industries – these professions that I love dearly, writing and media and book publishing – they’ve become so intensely dependent on a few big platform companies for their economic health and survival. And so the dictates of the big companies end up having this hugely distorting effect on everybody who depends on those companies.

I see it in media all the time, where when Facebook decides that it wants to switch to video, it wants to prioritise video, all of a sudden every media company in the world makes these incredible investments in producing video, even if video isn’t the thing that they do well. And it comes at the expense of money that would otherwise be spent on the written word.

Or to step back and look at it more generally, it’s that these platforms suck up advertising in a way in which media simply can’t compete. Some of that’s fair wins on their part, but we have to think about these guys also as parasites, who are media companies who don’t produce any actual media. They manage to skim the process without making any of the investments or expenditures, and the result has been a famine in media over an extended period of time.

So the anger that you had when you were writing the book, you still have that now?

Yeah, you know, I didn’t really achieve catharsis.

What advice – if you could go back and talk to 2012 to 2014 Frank or if you saw someone in the same position that you were in over that second period at the New Republic, pushed by the business side to create digital content or snackable content, what advice would you give them?

When I go back and I revisit the New Republic experience in my head, the thing that I wish I did differently was spend less money. When Chris Hughes came I was totally seduced by the prospect of becoming something bigger, shinier, and better. That rather than having a saviour who would save the New Republic as it had existed, I got suckered into the vision of transforming the New Republic into something closer to the New Yorker, which was just an entirely different scale of expenditure… And in retrospect, I wish I’d just preached restraint. Because, I think if we hadn’t lost quite so much money I don’t think Chris would have ever gotten antsy, I don’t think we would have ended up in a crisis – or I don’t think he would have perceived there to be a state of crisis, as he did in 2014.

I just think it’s always the temptation that when you have a new patron… We tend to associate success with scale, whereas excellence can exist in niche forms. And I would have been a lot better off, Chris would have been a lot better off, if we had curbed our pursuit of scale.

Do you think there’s any case to be made for publishers trying to outright reject or turn their back on digital metrics, or perhaps even turning their back on Facebook, focusing on print editions perhaps?

Yes, I think it’s actually happening. It’s a long, slow parting of the ways, but I do have this sense that Facebook is shifting its emphasis away from journalism, because journalism has turned out to be so fraught for Facebook itself. Journalism, politics, these are the things that bring controversies over what’s real and what’s fake, over how the platform could regulate itself for the good of the citizenry. And those are questions that Facebook ultimately doesn’t want to have to address because they’re so complicated and there’s a lot of risk involved.

So I think Facebook is going to peel away from journalism. It’s going to hurt journalism in the short run, but journalism is going to have to accept the fact that its traffic numbers are going to drop, that its digital advertising is never going to be what it hopes it’s going to be. Over the long run that’s healthy because it’s going to force journalism to refocus on subscriptions, and it’s going to enable journalism to liberate itself from some of the pernicious metrics that Facebook uses and which have come to govern journalism.

And so you think there is a sustainable model for writing and for magazines?

I do – but I fear that we’re going to experience greater pain in the transition to that sustainable model. That journalism will probably shrink – shrink even more – before it reaches the point of sustainability. It’s a pretty terrible thought to entertain, but I’m guessing it’s inevitable.

We’ve started to see this here [in the U.S.], where some of the big digital publishers have started to shed employees, kind of in the aftermath of all Facebook’s shifts. So like Vox fired 50 people last month. It’s attributable to the fact that Facebook had started to downgrade journalistic content.

There’s not just a tension between media companies and publishing, and Facebook – I was interested in this connection I noticed with Amazon. Your author bios on Slate and the Atlantic, when they mention your new book World Without Mind the link they provide is to Amazon. I’ve noticed this as well with book reviews on the New Yorker, a lot of the time they’re linking to Amazon. And I was just genuinely curious, is there an explanation for that?

Because it’s the unthinking choice that American consumers make when they purchase basically everything. Has Amazon amassed that kind of dominance in Australia?

They opened their first warehouse in Melbourne only a couple of months ago, just in time for Christmas, and there was a small – it was actually quite a small news item. I don’t think people, especially businesses, quite understand what’s coming for them in the way that Amazon has consumed the States. I get a lot of books off Book Depository and I think the brick-and-mortar stores have certainly felt some of that, but I haven’t seen an independent bookstore close… yet.

Lucky you. If Amazon decides that it wants to win in Australia, it will win, because its ability to sustain losses is so deep. Can I just give you a word of warning about Amazon?

Yeah sure, please, I’ll pass it on.

Okay, so, you know this guy Donald Trump? I think that if you look at a lot of the sense of displacement that so much of America feels right now, it’s attributable in some ways to Amazon. Because, a long time ago, our main streets were decimated, and then we had these malls, and we had Walmart, but they’ve struggled to survive. Well, malls have struggled to survive in the face of Amazon, and even Walmart hasn’t quite figure out how to respond to the power of Amazon.

What happens when you lose commerce, when commerce becomes so concentrated, is that people stop going to stores. And you lose all of the social interaction and sense of community that comes with that, and you start to lose jobs, as well. You can’t attribute all of that damage to Amazon, maybe you can’t even attribute most of that to Amazon, but Amazon has played a role in eroding something fundamental about the fibre of the nation.

Can we switch back to Facebook and publishing – I’m sure you’ve read the Wired piece about the last two years at Facebook. That piece, I thought it concluded on a note of optimism. The journalists, Nick Thompson and Fred Vogelstein, they believe that Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg have finally come to accept that they’re not just a platform, they’re also a publisher. What do you think about the idea that Facebook and these companies might just govern themselves appropriately according to their moral compasses or because of their own sense of duty?

I don’t buy it. I think that ultimately you just can’t count on these companies to govern themselves. Too many of their incentives push towards increasing the boundaries of surveillance on their customers, and this is what we’re constantly learning anew. So we have the scandal right now over Cambridge Analytica, which is a company that was working with the Trump campaign to come up with psychographic portraits of voters that were going to be exploited on Facebook, and they were tapping Facebook in order to get data about users. And unfortunately I think that Facebook’s comparative advantage is its data, and it’s always going to try to protect that, and the way that it will protect it is by finding new, invasive ways to find out more about you.

This is separate from the problem of whether Facebook can regulate fake news, but what I’m getting at is that, you know, Facebook is never going to be able to regulate itself. It’s almost inevitable that we’re going to arrive at the day when government regulates the technology companies. The fact is that we’re only belatedly understanding the abusive tactics used by these companies, so it feels like each month we awake anew to some different horror. And all these horrors will add up and will take their toll, and the only reason to be optimistic is that they’re going to lead to government finally providing a counterweight to these companies.

I’m sure you’ve also read John Hermann’s book review of World Without Mind, and in that review he uses the words – when he’s talking about your calls for government regulation – he uses the words “idealistic, plain crazy, or just plain impotent”. What do you think of his assessment?

[Laughs] I always place myself on the spectrum between idealistic and plain crazy. I think the thing is that everything is changing so quickly, and the sense of what’s politically possible expands almost every day. So when I first proposed my book, I felt like this was a very strange subject, and it felt like a very quixotic pursuit. And when I tried to explain it to people I felt like they gave me funny looks. But then, over time, calls for regulating the tech companies are shifting closer and closer to the centre of American political discourse, and certainly European political discourse. We’re not there yet, but I don’t know that we’re that far off. Does that just sound plain crazy?

It certainly sounds idealistic, although what the Europeans are doing is good. I notice there’s a lot of talk of thresholds in your book, and the big threshold, the threshold above all the other thresholds, is this concept that we’re going to get to a point where thinking is eroded so much that we can’t actually claw ourselves back… I have a friend who’s got this joke about footballers, rugby players, who play one game of rugby and after that no longer have enough brain cells to realise that playing rugby is bad. Are we in danger of the same kind of lock-in happening with Big Tech?

[There’s a point at which] tech becomes a barrier to being a present human being. And the presence that we have in conversation is not disconnected to the presence that we have in our states of contemplation. And if we’re always connected to the machine, we really do surrender some core element of our mental processes.

This is a question that’s not really unique to issue of the tech giants and the digital age, but it is certainly made more pressing by it: how do people who are engaged in intellectual life, how do they reach across to people who don’t care so much about ideas? How do you reach across the aisle, so to speak?

It’s funny you mention that, because, as I said before, I’m actually kind of engaged in doing this right now as we speak, on my way to the evangelical college, where I want to try to have this type of conversation with people who are hostile to elitist thinking. I think part of it is that we need to be unabashedly elitist.

The temptation of intellectuals over the course of the last generation is to try to dumb it down, fun it up, popularise, decamp from the little magazines and the ivory tower to become public intellectuals – and having intellectuals writing in accessible prose and the like. But I also think it’s important that we don’t degrade the core of what we do in the process. One of the things that we may need to do is nurture the life of the mind in an almost counter-cultural way as we go through these transitions. The life of the mind is something incredibly precious, there’s this gorgeous heritage of ideas that we have, and it’s important that we don’t let it fall into disrepair.

On the last page of your book there’s a similar sentiment. You say that “we need to protect ourselves”. I wanted to ask you what that looks like: what does protecting ourselves from the tech giants involve?

There’s a measure of self-awareness that’s critical: we need to understand the addictive powers of the technologies. To protect ourselves from them there are all sorts of mechanical things that one should do as good intellectual hygiene, you know, in terms of shutting off the notifications on your phone, stripping Facebook off of your phone, not sleeping with your phone.

I make the case for why continuing to read paper books preserves a sanctuary in our lives where we’re not being surveilled, where we’re disconnected from corporate stores, and where people are not trying to steal away our attention. And I think it’s that spirit of resistance, of trying to maintain the quiet spaces in our lives, that helps preserves us as human beings.

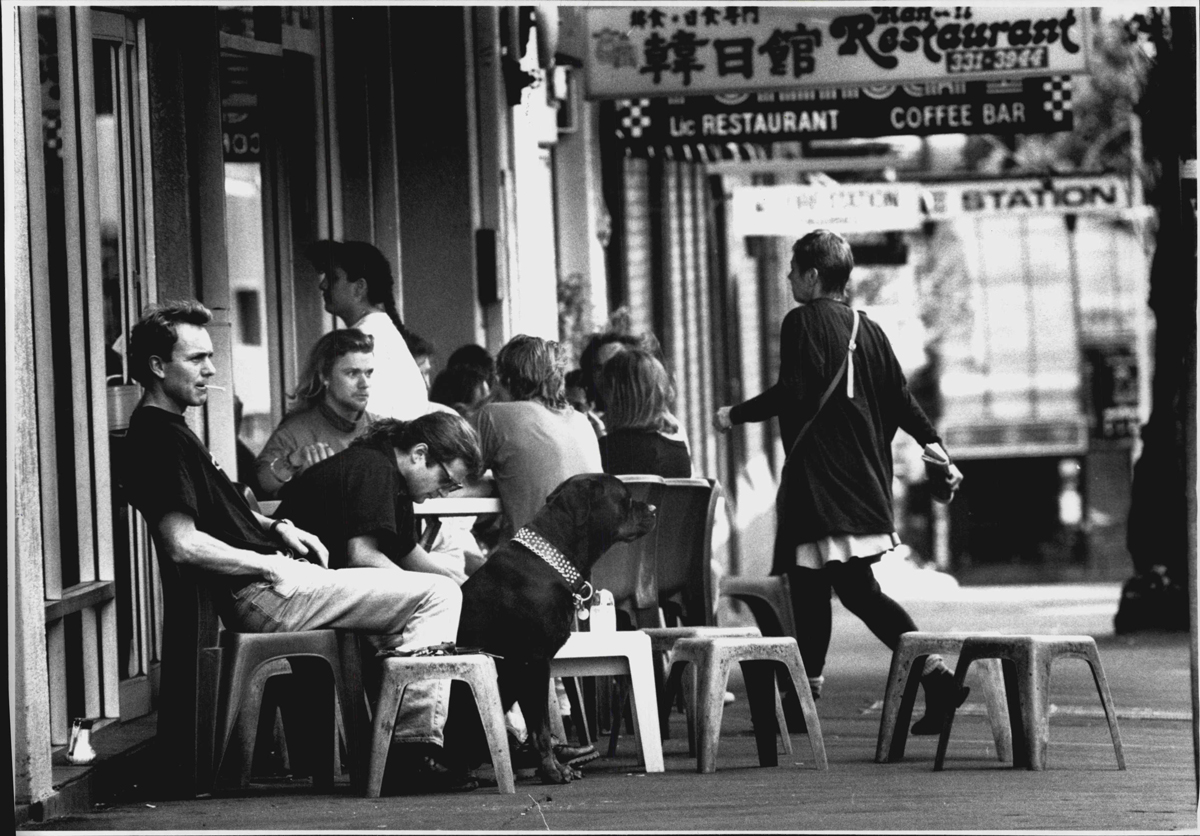

Franklin Foer is speaking at Carriageworks on Saturday, 24 March, at 6:30pm, as part of UNSW’s Centre for Ideas