When I met Henry Rollins in 1993 he had big problems. Big deal. He already had quite the rep – Tom Cruise planted inside The Hulk’s body, an All-American boy ever-ready for violent combustion. Instead of that combustion, Rollins quoted Nietzsche and John Coltrane, hung out with Nick Cave and Sonic Youth, expanding his heavyweight music career with a publishing wing that dug out the real hard core, great and terrifying moral writers like Hugh Selby Jnr, the author behind Last Exit to Brooklyn and Requiem for a Dream.

Rollins: he was something and he was nothing to me.

Prior to meeting him I was not a fan. He just seemed like some pumped-up dope who printed book after book of his journals. A walking bunch of tattooed muscles with angry eyebrows. My real ‘beef’ was his music with Black Flag, lauded by many but to my ears mono-rock ranting. American punk? No thanks. Reputedly he was the leader of a new ‘straight edge’ movement, someone who took no drugs or drink. I’d seen him doing push-ups in his shorts before he went on stage one night. My friends and I were off our dials and laughing. This wasn’t poetry, that wasn’t danger, it was sexually-frustrated aerobics.

What changed my mind? The Rollins Band album, The End of Silence. Triple heavy with a dose of free jazz slowing it down to molten. It was as if he had found a spectrum for rage and loneliness and honesty I could not imagine. An opening song like ‘Low Self Opinion’ hit me like a punch in the face. Manifesto rock for saving yourself. What a blast.

So, Rollins arrives in Australia – not for his music (damn) but for his first ever ‘talking tour’. He is going to get on stage and speak about whatever, improvising stories about his life and opinions. On stage he is surprisingly funny and amenable as well as powerful. Every night is totally different, but he has one big story that unravels and grows. I only discover its seed when we first catch up.

A few weeks previous his best friend Joe Cole was shot to death right in front of him as they returned home with a takeaway dinner. The Rollins I meet is not much more than a gun blast himself. He has so much anger and hurt he can’t place it anywhere. Literature and music have given his past rage a place and purpose, but this new pain is more than he can locate. We walk through Surry Hills towards a café for our interview, a pale skinny rock journalist making small talk, an underground rock star shattered by tragedy. And though neither of us bonds we communicate like some big mistake meant to happen. Henry Rollins, trust is hard. But yeah, we met. It was just like you sang it too: “Unable to express the pain of our distress.”

See below for Mark Mordue’ original interview with Henry Rollins in 1993.

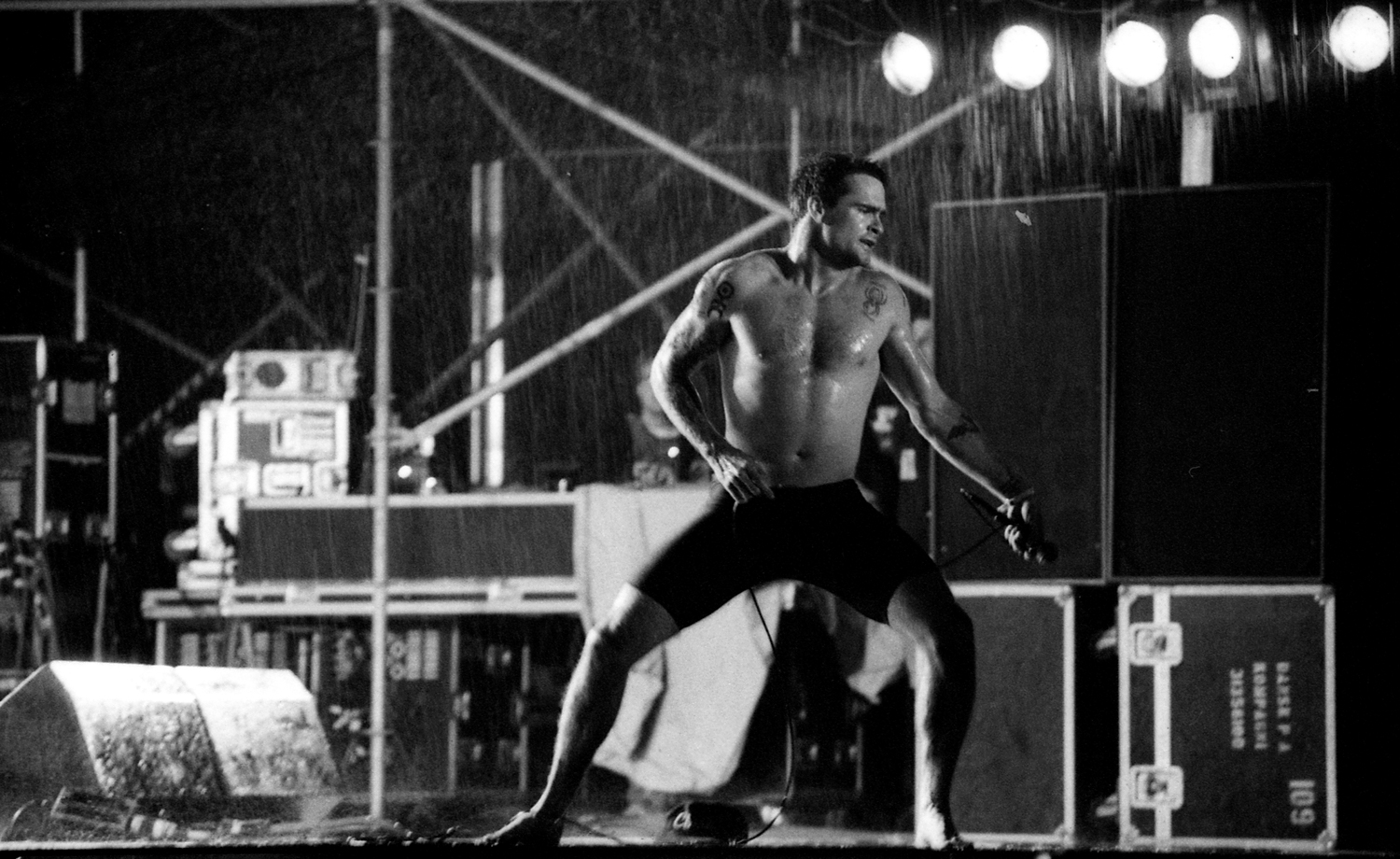

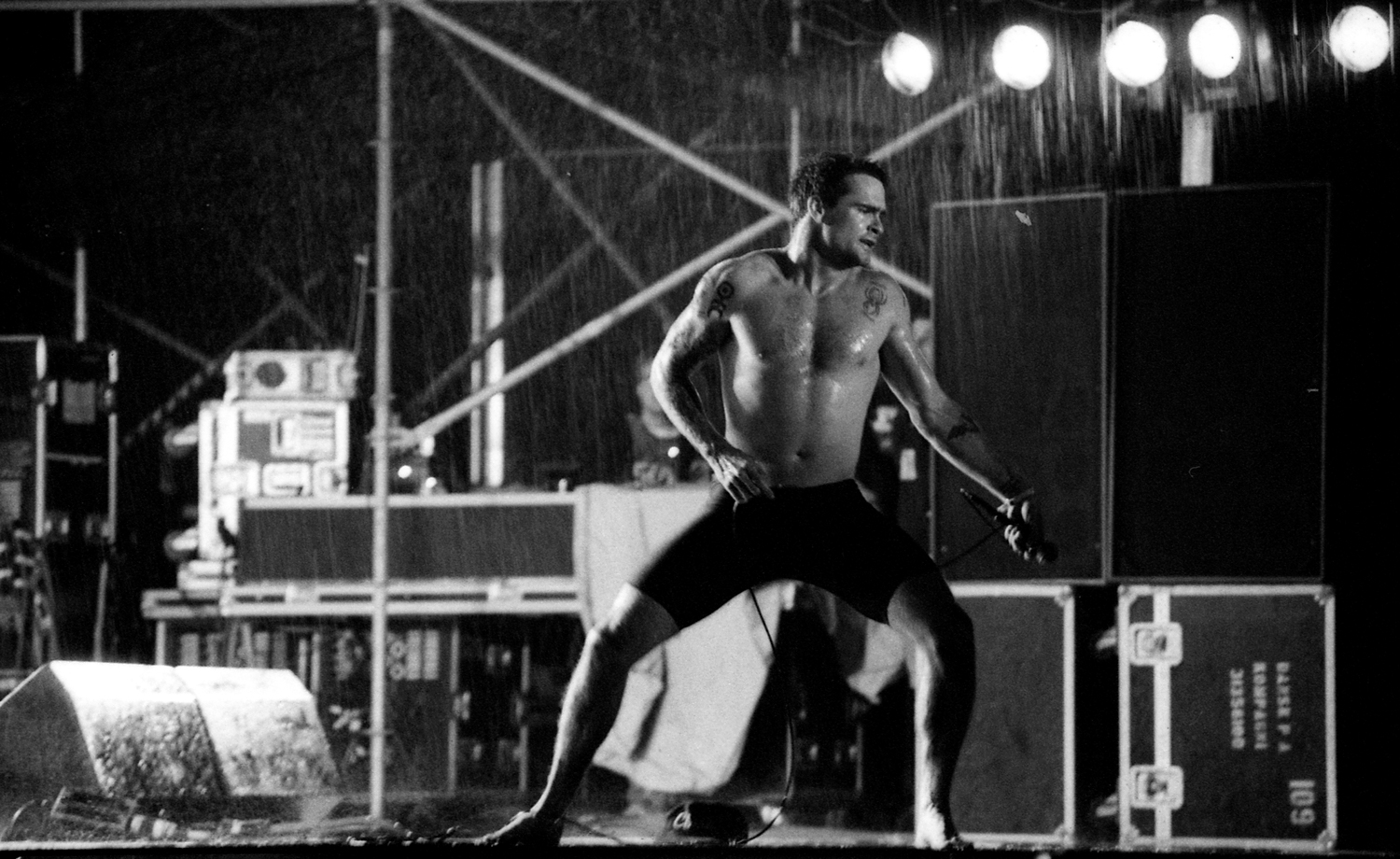

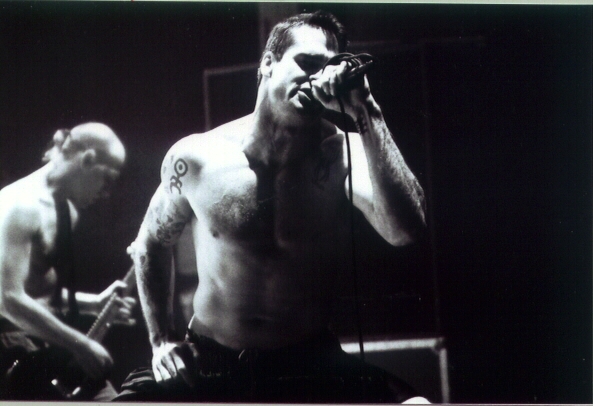

Rollins says his idea of perfect happiness is when “I’m in the middle of something. When I’m in motion. When I am an active verb.” Photography by Pelle Sten

The Bright Stuff

Henry’s Rollins and his music of ascent

Can you remember the last time you were really scared? Henry Rollins shifts in his seat, and his whole body seems to ripple with the answer as if he’s making a threat. “Yeah, I remember the last time I was scared. December 19th, when a guy had a gun to my head. And then two minutes later he shot my friend and blew his face all over my front porch five feet away from me. That was pretty scary.”

In his book, Pissing in the Gene Pool, Henry Rollins calls honesty “the isolation machine.” Spend some time with him and you begin to get that honesty, an honesty so intense, so physically, absolutely there it’s exhausting and ultimately distancing. Henry Rollins prefers his own company to most human beings and despises “cop-outs” like drugs and alcohol. Rollins lives the ecstasies and agonies of solitude, working out on weights or meditating, reading Nietzsche and Hugh Selby Jr and listening to Coltrane or Hendrix. The only other time he’s happy is when he’s on stage with the Rollins Band, a maelstrom he finds joy in because “it’s like a f*cking war zone.”

On most of his books and records he is simply credited as ‘Rollins’ – no Christian name, no soggy, false familiarity, no waste of breath on an unwanted consonant or vowel. Just one word. Rollins. Suggesting something hard and moving from the self-proclaimed “part-animal”, “part-machine.”

The man who lost his face and life was Joe Cole, Rollin’s best friend and working partner. “We were like brothers,” says the ultra-intense Rollins. Cole and Rollins were bailed up on their way home from a grocery store on a vaguely happy night in Venice, LA.

Less than a month later Rollins is in Australia, trying to work off his grief on a national tour of “readings” to promote his recent book, One From None. “Readings” though, hardly accommodates Rollins’ free-raving performances of some 90 minutes or more. In three shows he never repeats a single phrase or tale, while also negating expectations that his monologues might only evoke violent descents into Rollins’ private vision of diseased America.

Instead, Rollins is comical, self-effacing, boyish, a silver-lined cloud. The weight of his stories, from the war veteran father who bullied and disciplined him with anthem singing, flag saluting and racism, to the step brother who sexually assaulted him, remains a submerged force. He wants to be liked. The isolation machine cries out for affection – but it’s deceptive; you’re closer to him in a room of 1000 people than sitting with him over a coffee.

Each Rollins show in Sydney goes deeper into his private history, till the last when he relates, over half an hour, just how Cole was murdered and how it felt, standing with his hands above his head inside the front door of his house, hearing gunshots and entering some eerie suspended place in time where his only thought was “gunshots sound strange in this room. That’s all I kept thinking over and over.” And then he ran. By the story’s end a few people have actually fainted, and many are crying.

At his best, Rollins is a stormtrooper into the American heart of darkness, with a battlemap etched in personal struggles to exist and confess his contempt, compromises and loathing. At his worst, Rollins is a dead end, all sound and fury signifying nothing, whose writing slumps into puerile toilet-wall ranting and that typically American extravagance, the confessional as a form of debased therapy. Ask the 32-year-old Rollins about his family and he’ll tell you. “My mum and dad were divorced right after Kennedy got killed and my dad remarried this horrible woman. She already had a kid from a previous marriage, a really psychotic guy. He sexually assaulted me.” Do you hate him? “No. Don’t even think of him at all. Haven’t seen him since I was about 16. Don’t even know if he’s alive or dead. Couldn’t give a f*ck.”

Rollins says his idea of perfect happiness is when “I’m in the middle of something. When I’m in motion. When I am an active verb.” He claims his favourite word is “Destroy. It is total. Powerful. Sexual. Chuck D from Public Enemy had a great quote, ‘When I work, I destroy.’ Wish I’d said that first.” The trait he deplores most in other people? “Weakness.” The trait he deplores in himself? “Weakness.”

Extremity, commitment, intensity… Rollins is a purist who first made his mark singing out-front of the now mythical LA hardcore act, Black Flag. Since their early-80s heyday as the supremely brutal entity on the West Coast punk scene, Rollins has tightened his musical focus, flexing the muscles of anger and subversion with military precision in the Rollins Band.

The last album by the Rollins Band, The End of Silence, marked his first release on the corporately well-connected Imago Records. One From None is out, with another book, Black Coffee Blues, soon to follow on the publishing company he started with Joe Cole, 2.13.61 (Rollins’ birthdate). Writers like Nick Cave (“in the last picture ever taken of Joe Cole alive”), Alan Vega (of Suicide) and Hugh Selby Jr (“easily one of the best friends I have”) are all putting their work out on 2.13.61. Last year’s spoken-word tour was recorded and has now been released on Imago/2.13.61 as The Boxed Life.

“Yeah, things are looking great,” observes Rollins. “It’s been kinda hard in the last month to deal with all that because the facts are I’m getting real popular here and there, I got a great new record and I’ve got money in the bank for the first time in my life. I’m making money. I got my book company happening. I’m writing good stuff. And the only drag is my main inspiration for doing all this stuff is dead. And I’m not trying to be selfish. It’s just that I feel guilty when good things happen now because I lived and my friend died. That’s been a hard thing to get used to.”

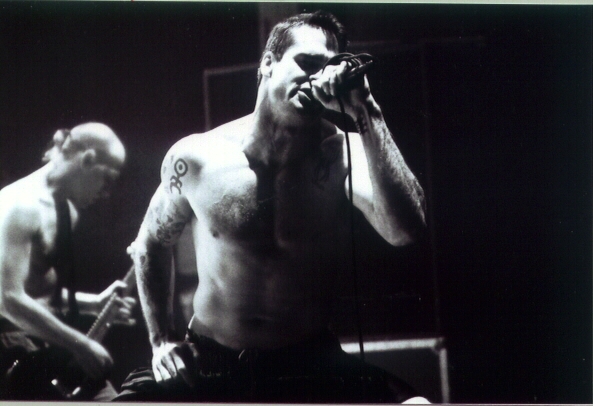

Photography by Jon Iraundegi

The long shadow of Joe Cole looms over everything. No doubt there will be a book dedicated to his memory – just about all Rollin’s books seem to be dedicated to the memory of someone or other. Cole had worked with Rollins ever since he was a roadie for Black Flag. They were on the verge of success. But American dreams don’t shape up that way, least of all in the territories Rollins inhabits, like his now-former home in Venice, LA.

“See, In America,” Rollins explains, “if some guy gives you shit on the street, like ‘Hey man, where the f*ck did you get that haircut?’ you don’t ever go, ‘F*ck you.’ You don’t do that. Because the guy’ll go, ‘Oh yeah…'” Rollins forms his two fingers into the imaginary barrel of a gun, pushes it to his head and says “BOOM!” After the silence has cleared, he continues, “Everyone is cocked and loaded these days. F*cking people get shot in traffic accidents. Our road manager’s girlfriend’s brother got wasted at a stop light. A guy opened up with a f*cking Uzi right in the car next to him.”

“Every once in a while I think of moving, I mean, I moved to California to join Black Flag and I stayed there because I like the fact that I’m not near the town where I was born [Washington DC – America’s murder capital]. And I like that. I don’t want to f*cking live and walk on the streets I grew up on. I don’t want to walk down the street and go, ‘Man I stood here 30 years ago.’ I hate that kind of sh*t! It’s like going backwards. And to leave home and become the person that I became was a lot of pain. Now I’m starting to think that California is just… I don’t want to grow old in that city. I just think it’s for losers. Los Angeles sucks. And California’s f*cked too.

“But once you’ve been Americanised you have the stink of America on you. You never come back all the way. Living like I have in the last ten years, there’s a certain amount of paranoia which kinda gets ingrained in you. If you’re a sensitive person, the world gets harder and harder to live in. The climate of the world, in all the cities I’ve been in, is becoming more hostile. I just think that the powers that be are very cruel. They don’t give a f*ck. The rich are rich and the poor are poor. In America the distribution of wealth is obscene. I mean, the poor are really poor, and the rich are like… Bruce Willis! It’s horrible.

“Like the guy who wasted my friend. He’s just as f*cked up as everyone else. He’s just another victim of America. I don’t think the guy who killed Joe is a bad guy. He’s probably just another f*cked up guy filled with rage in a sh*thole. It takes a lot of rage to go out and shoot someone in the street. I’m not saying I want to move in with this guy or buy him lunch. But in a way I can’t hate him and not hate myself too.”

Rollins expresses a furious essence when he says, “I deal with my rage. I was raised with a lot of violence, a lot of intimidation, a lot of humiliation. And I had to reinvent myself. I had to become someone I could respect because I didn’t used to be that kind of person. I would pit myself up against a lot of physical and mental tests, trying to strengthen myself. Now I can live in my skin and stand myself. I wasn’t always able to stand myself.”

That skin is an icon trail through Rollins’ life, a tattoo-covered physique so tensely developed you’d expect to hear his last decade was spent in gaol rather than rock & roll. “LIFE IS PAIN, I WANT TO BE INSANE” is the slogan around two skulls on his biceps, above and below the four solid black bars that served as Black Flag’s logo. There are many others, but the Rollins piece de resistance is a blazing, huge sun across his back with a mutant tarot face at its centre and the words “SEARCH AND DESTROY” carved across his shoulder blades.

Yet in spite of looking like your worst Cape Fear nightmare, people do like to confront Rollins. When asked about this, something crestfallen opens Rollins’ steely gaze. It’s a shock to encounter a handsomeness beneath the hooded looks that is fresh, All-American and not too far from Tom Cruise in its boyish classicism.

“That’s true. People do challenge me. I don’t always understand why because they don’t really know it, but I’m on their side. I’m not doing this to go, ‘I’m better than you.’ I’m not dropping the gauntlet down, not even close. I want to be a friend. Sometimes I feel very ancient. Some of the things I’ve been through… Like if you make your living in front of people for many years, and you have thousands of people who tell you that they love you, that they love what you do… Lots of girls telling you they’re in love with you or obsessed with you or whatever, and you go through a lot of these instances. It’s just…

“I can’t describe what it’s like to be in front of a bunch of adoring people every night for 12 years. After that, it does something to you. It alters your DNA. At this point there’s nothing some women can say to make me fall over backwards. There’s nothing you can say that will scare me. I’m not trying to come on as a tough guy or anything but after what I’ve been through, you can kill me but you can’t scare me. The more you’d try and scare me, the more thick I would become.”

Something in me would like to shake his cage, but I can’t help but feel he is shaking by himself within it. Certainly, he knows “depression. It’s a hard rock to crawl out from under. Sometimes I can, sometimes I can’t. I’ve always had a big problem with depression. That’s why I do what I do. I’m trying to balance out all the things that want to drag me down the drain.”

Don’t you feel your subjects have become a part of your problem? That what you keep looking at keeps on attracting you?

“I’ve thought about that a lot. It makes me think of a line I’ve read out of Nietzsche, and for years I never understood it. And then one morning I got up and had… understanding of it. I’m sure you’ve heard it. ‘He who looks into the abyss, finds the abyss looks into him.’ I have an understanding of it now – you can explore this emptiness and sadness and all of a sudden you are empty and sad. Well, the things I write and talk and sing about, I guess, in one way or another, I’m obsessed with. It’s my life. But I’m always looking to grow, to ascend. I’m not into a backwards, downwards thing. I’m, into a forward and upward thing. I’m getting stronger and brighter as I go.”