Bethlehem, December 2017. Rockets are screaming up into the night sky, exploding with ear-splitting bangs, again and again. The sounds of a battleground. But on the night of December 2, these are only fireworks and the occasion is the annual lighting-up of the giant Christmas tree in Bethlehem’s Manger Square.

A huge crowd of people cluster around, their upturned faces caught in the flickering light of thousands of smartphones held high, chanting a countdown as a light show streaks across the tree, before a canopy of bulbs overhead, and the whole tree itself, flash into gaudy colours and the firework show begins. All to the thumping beat of Arab pop.

It’s an event that might have sent the original ox and ass running for the hills: more Atlantic City than ‘O Little Town’. Across the square, however, in a small arched doorway, another Christmas message has appeared — silently and unnoticed, in the past day or so. Painted on the door in cursive English script, it reads: “Peace on Earth”. There follows an asterisk, in the shape of a Bible-storybook star, and underneath, in much smaller letters: “Terms and conditions apply”.

Just a few days later, the unrest following US president Donald Trump’s official recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital would vividly illustrate those terms and conditions, and this salutation, from the British graffiti artist Banksy, would take on a new irony.

Banksy’s unseen presence in this part of the West Bank has become increasingly powerful. Interviewed over email (the only way to communicate with the famously anonymous artist), he says jokily that when he first came to the region, “I was mainly attracted by the wall: the surface looked like it would take paint very well.”

The wall in question is, of course, the impenetrable 30ft concrete-and-wire barrier, with its guarded watchtowers, that runs alongside and through the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. It carves through Bethlehem in a strange double-U shape, to ensure that the holy site of Rachel’s Tomb remains on the Israeli side.

This serpentine course means that there is an awful lot of wall in Bethlehem, and alongside the Aida refugee camp on its outskirts (home to more than 5,000 Palestinians); and the wall does indeed take paint well. The full length is a riot of graffiti, by a mass of different hands, painted and overpainted again and again — many recent ones are giant cartoons of Trump, including one in which he is hugging and kissing a watchtower.

Banksy has been working here on and off since his first visit in 2003. By that time he was already well known in Britain as a clandestine street artist, first in his native Bristol, then in London and elsewhere. But his move into the commercial big time was yet to come. Techniques for illicitly removing his work from walls were rapidly being perfected, while Banksy’s then gallerist, Steve Lazarides, was a keen legal marketer.

When in 2007 Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie forked out a cool £1m for a Banksy work, other celebrities — among them Christina Aguilera, Damien Hirst and Kate Moss — followed suit. Justin Bieber had Banksy’s famous image of the little girl with a balloon tattooed on his forearm. As Lazarides put it at the time, buyers in this Banksy craze were “rag trade, City boys or celebrities, [usually] under 45”.

In 2008, “Keep It Spotless (Defaced Hirst)” fetched US$1.87m at Sotheby’s; it remains the artist’s auction record. Since then, various houses, shops and even sheds that host Banksy works have come to the market for several times their actual property value. No one knows, though, the prices of the illicit sales of work stolen from walls.

Despite (or perhaps because of) his market success, Banksy gathered his share of detractors. He was accused of copying ideas, especially from French street artist Blek le Rat, and often regarded as a prankster whose hit-and-run visual aphorisms were amusing rather than deep. Yet all the commercial activity and sales of merchandise and new work via Pest Control, the company he set up in 2009 largely to control the flood of fakes, mean that Banksy’s personal wealth is conservatively estimated at some £20m.

Despite the artist’s best efforts, the faking, thieving and destruction of his works continues everywhere in the world. In Bethlehem, too, powerful images have often disappeared surreptitiously, sometimes almost as soon as they have appeared on surfaces around the town or on the wall itself. One 2007 painting that raised hackles locally, of a donkey having its identity papers checked by a heavily armed Israeli soldier, has vanished and is — according to Banksy’s agent Jo Brooks — currently for sale on the international market. What’s more, cowboy gift shops, unashamedly selling Banksy knock-offs and copies, are everywhere. There is even a large one, bearing its slogan “Make hummus, not war”, right up against the wall of Banksy’s hotel.

The Walled Off hotel (pronounced Waldorf) was opened in early 2017, aimed mainly at international visitors, with a range of rooms from the luxurious to a no-frills bunk-bed option at $60 a night. Starting with the over-lifesized plaster chimpanzee dressed as a 1930s bellboy at the front door, the period luggage he is carrying spilling ladies’ undies, the place is packed with Banksy-ish visual jokes, as well as his artwork. It proudly claims to be the hotel “with the worst view in the world” because it stands barely five metres from the looming expanse of the barrier, which at this point runs along what used to be a bustling shopping street, now a semi-deserted, rubble-strewn, potholed lane.

Graffiti rules here: this must be the only hotel where the guest information sheet includes advice about where to buy paint and hire ladders. From its pleasant terrace, the colourfully graffitied concrete in front of you seems almost jaunty in the bright daylight. At night, though, the wall’s full sinister menace is inescapable.

Banksy is not new to ambitious enterprises: two years ago he set up Dismaland, a temporary “bemusement park” in Weston-super-Mare. Offering a dark twist on Disneyfied family entertainment, it was a place, as its publicity said, “where you can escape from mindless escapism”. Two years before that he announced a “residency” in New York, with plans to create a work somewhere around Manhattan and Brooklyn on each day of his 31-day stay. One of his stunts was to set up a stall beside Central Park, selling authentic signed pieces for $60 each. Only three were sold.

But a hotel? In such a location? Given Banksy’s persona, it’s hardly surprising that some people assumed it was a joke. But this time, it seems, the joker was in earnest. “To be completely honest, I knew very little about the Middle East when I first went there. You know — just a sense from the news that it was a bunch of people habitually killing each other,” he says.

“On my first trip to Palestine I arrived at night and was driven straight behind the wall. So I assumed the poverty, the donkeys, the water shortages, the electricity blackouts were all just facts of life in that part of the world. I was completely astounded when a week later I left through the checkpoint into Israel and 500 yards down the road there were expensively paved shopping centres, roundabouts planted with palm trees, brand new SUVs everywhere. Seeing the disparity between the two sides was shocking, because you could see the inequality was entirely avoidable.”

Over time, though, his involvement with the region has deepened from visiting graffiti artist to investor. The main reason he bought an old pottery works and converted it into a hotel, he says, “was for Wisam, my fixer”. This is Wisam Salsaa, now manager of The Walled Off, and the artist’s local representative — in everything, it seems, since keeping yourself entirely secret requires devoted allies. “I’d become good friends with [Wisam],” Banksy continues. “But the occupation was making him so fed up he was on the verge of leaving Palestine for a job washing dishes at a Belgo’s in Rotterdam. This is a man who runs several businesses, speaks five languages, employed half a dozen people, who was intelligent, brave and funny. I thought — it’s vital people like him don’t leave.” And then, in the inevitable twist, he adds, “Plus I didn’t want him coming to sleep on my couch.”

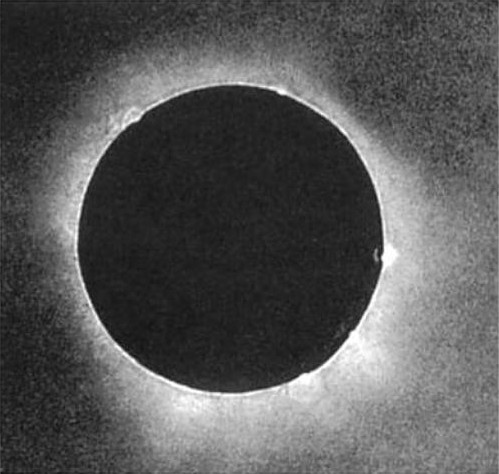

Iconic Banksy street art picturing a white dove with an olive branch in Bethlehem on 1st

April, 2016 in Bethlehem, West Bank. Photography by Sam Mellish/Getty

On the morning after Bethlehem’s tree-lighting party, the acclaimed film director Danny Boyle is standing in the middle of the dusty car park adjoining the hotel. Salsaa is there, organising everything as always, and so is Riham Isaac, Boyle’s Palestinian co-director in this newest Banksy project. There’s a scaffolding stage with a lighting rig, a few rows of plastic chairs, a huge camera boom, a couple of bickering sheep and an elegant white donkey tied up in the shade. It doesn’t look like a place where, in just a few hours, they will produce

The Alternativity, a Christmas play performed by local children.

This morning, too, high on the wall overlooking the car park, a new Banksy piece, in his signature stencilled style, has appeared. It shows two winged cherubs, one holding a crowbar, tugging furiously at a gap between the concrete slabs of the wall, trying to jimmy it open.

Will The Alternativity hold a similarly political message? Apparently not. “I just got an email from Banksy out of the blue,” says Boyle. “I’d never been in touch with him before, though I knew his work of course. I respected what he was doing. And he just asked me to do this, and I said yes.” Boyle was paid £1; the contract describes him as “presenter”.

On an earlier visit, Boyle had recruited Isaac, a local theatre director and teacher, to work on the project. She explains that she found and auditioned the children to perform and sing through Facebook. Many of the locals involved are Christian, though there are one or two hijabs under the Santa hats worn by the choir.

A film of the whole project is under way, directed by Jaimie D’Cruz, who worked with Banksy on his 2010 documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop. D’Cruz tells me that, even for Boyle, it was hard to hire equipment here. And although it is happening only a few hundred yards from the nearest checkpoint, three Israeli photographers declined to take pictures for the FT.

Yet it feels peaceful, almost sleepy. Dusk falls quickly in the winter afternoons here, and when several hot dusty hours have passed, during which the two children’s choirs, the dancers and performers, even the donkey, have rehearsed the play, the five o’clock start is in darkness. Strapping security guards in military boots, their bulletproof vests with the strangely cosy slogan “PalSafe” on their backs, stride around as the lights start to glitter and the transformation of the dingy car park is complete. The hideous wall looming just behind us is forgotten.

People arrive, dressed up and excited — families with noisy young children eating ice cream, older people, some local dignitaries who get the few chairs while everyone else mills around. There’s a small number of foreigners. Then it begins: carols and songs, sweetly sung in Arabic and a little English; some slapstick; some dancing; Mary on that donkey, of course; three comic and strident “wise women” instead of the kings; and the Christmas story is told. Despite the magic wand of an internationally famous director and some very expensive touches (a noisy snow machine, for instance), it was a Christmas play like thousands the world over: strangely reassuring, absurdly touching.

The involvement of many dozens of local children and families in The Alternativity was a tribute to weeks of work on Isaac’s part. Banksy reveals a different aspect of the project: “The nativity was conceived as a rather clumsy Christmas stunt,” he says. “But almost as soon as the film crew arrived they reported back saying, ‘We’re going to have to reflect the local unease with the hotel,’ to which I said — unease? It turns out a lot of locals are rather suspicious of the project. In the end the Nativity play was wildly popular and has engaged with lots of children and their families. So the Nativity discovered a problem and then solved it — Merry Christmas.”

Salsaa, it turns out, also had his doubts, though for other reasons. “I didn’t know if anybody would come. I mean, why would anyone bring their children here, under this wall? Why would they want their children to see this?” His own three children, it turns out, didn’t know of the wall’s existence until he opened the hotel. The eldest is 14. “But people came to the play — they didn’t seem to mind so much.”

The Walled Off project throws Banksy’s anonymity into sharp focus. He seems so present — the new works popping up, the casual way people say, after the show, “Oh Banksy really liked the snow machine.” Was he there? Watching from an upstairs window? Mingling with the crowd? Or was someone livestreaming it all for him — and if so, to where? In an age obsessed with fame and name, he is a sort of alternative celebrity; but he is one, sure enough. To break cover now would be to ruin the brand — and here it is very clear to what extent the secret of his identity is in the hands of a few devoted people around him, who make his life and work possible. He obviously inspires a loyalty that runs deep. Even Boyle has not been face-to-face with him. “When I agreed to do the Nativity play, Banksy said, ‘Do you want to meet?’ And I said ‘No!’ We did the entire thing by email.”

The wider question about the whole project is — why? Do Banksy and his supporters believe that his art, or anyone’s art for that matter, can effect meaningful change?

During a visit to Aida, the nearby Palestinian refugee camp, it was noticeable how my guide Marwan Frarjeh spoke about the artist with familiarity and warmth. Establishing the hotel in what was previously a no-go area, he said, had brought some life and hope, not to mention international visitors.

Boyle has definite views about the role of culture amid such difficult political realities. “I worked in Northern Ireland for years,” he says. “To be honest I never thought anything would change there, it seemed impossible. But look, it did.” In Berlin, too, he learnt the hard facts about walls. “And that one came down, in the end.” He is currently working in South Africa, with its still painful apartheid legacies, and while he wouldn’t go so far as to attribute these important political shifts to the power of the arts, he says: “It’s about bringing culture, it’s always important. It’s essential, in fact.”

Banksy himself is modest, in answer to the question about the possible effectiveness of his art, and even if his replies — like the project itself — sometimes seem impossibly naive, he remains optimistic.

“There aren’t many situations where a street artist is much use,” he says. “Most of my politics is for display purposes only. But in Palestine there’s a slim chance the art could have something useful to add — anything that appeals to young people, specifically young Israelis, can only help.”

Reprinted from the Financial Times (originally published 15 December 2017)

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2017. Used under licence from the © 2017 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved.