Lately, I’ve been thinking about what I believe Bob Dylan called being a musical expeditionist. About the pavers and the lighters of the way forward. About the unsung, the masters that may have slipped through the cracks of popular culture. About being a seeker. And how, it’s all too damn easy for kids today, all the hunting is done for them. And it made me feel kinda sorry for ’em. Because what was once hard to find, obscure, difficult music is found today on a ‘tastemaker’ playlist.

But if it’s all at your fingertips, where’s the thrill of the hunt, the joy of the lucky find, the lifelong indebtedness for the introduction, that weird pride and sense of ownership that accompanies uncovering some mysterious wild magical sounds, known only to the secret few? Let alone the accompanying artwork… the liner notes… the obsessive studying of who played what on what record…

It’s great to see all these mini musical encyclopaedias, 16-year-olds digging on Can or the complete unreleased rehearsal tapes of the Velvet Underground, along with in-depth knowledge of who said what to whom during the recording of the seminal blah blah… but if having easy access to that once difficult-to-find stuff is simply normal, I have to wonder if this stuff loses its secret magic, its untouchable hard sought-after quality.

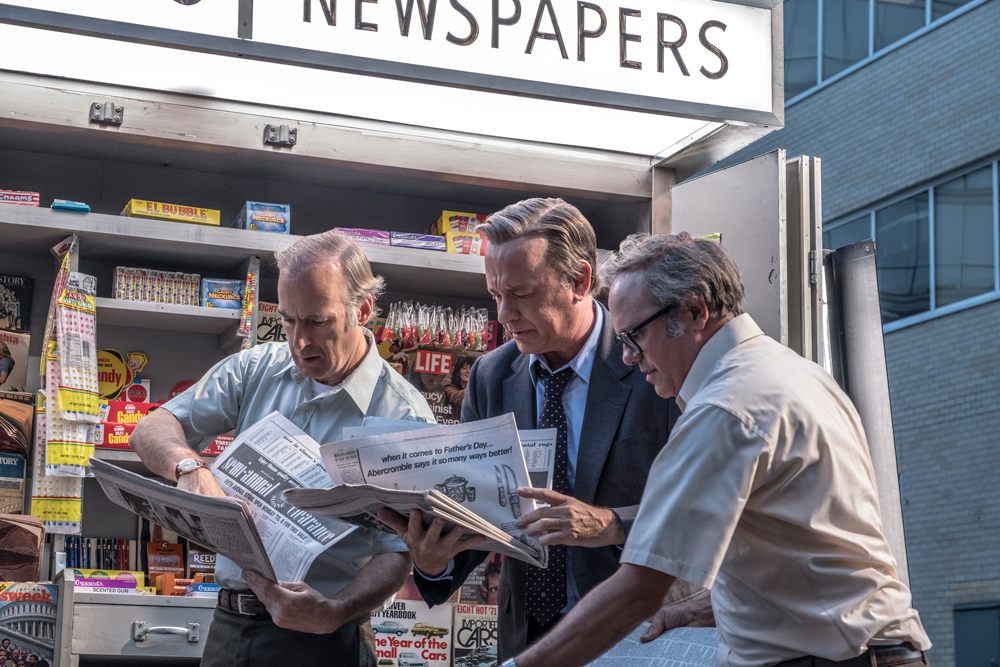

Is there something to be said for dedicating oneself to digging deep? The doco No Direction Home reveals that whilst young Bob Dylan was still in the process of self-creation, he was known for stealing his friends and mentors’ obscurest, most prized records – a theft he believed was necessary for his artistic growth, for his immersion technique. This technique involved listening to the recordings of his chosen masters over and over until they lived inside him, and their knowledge was his.

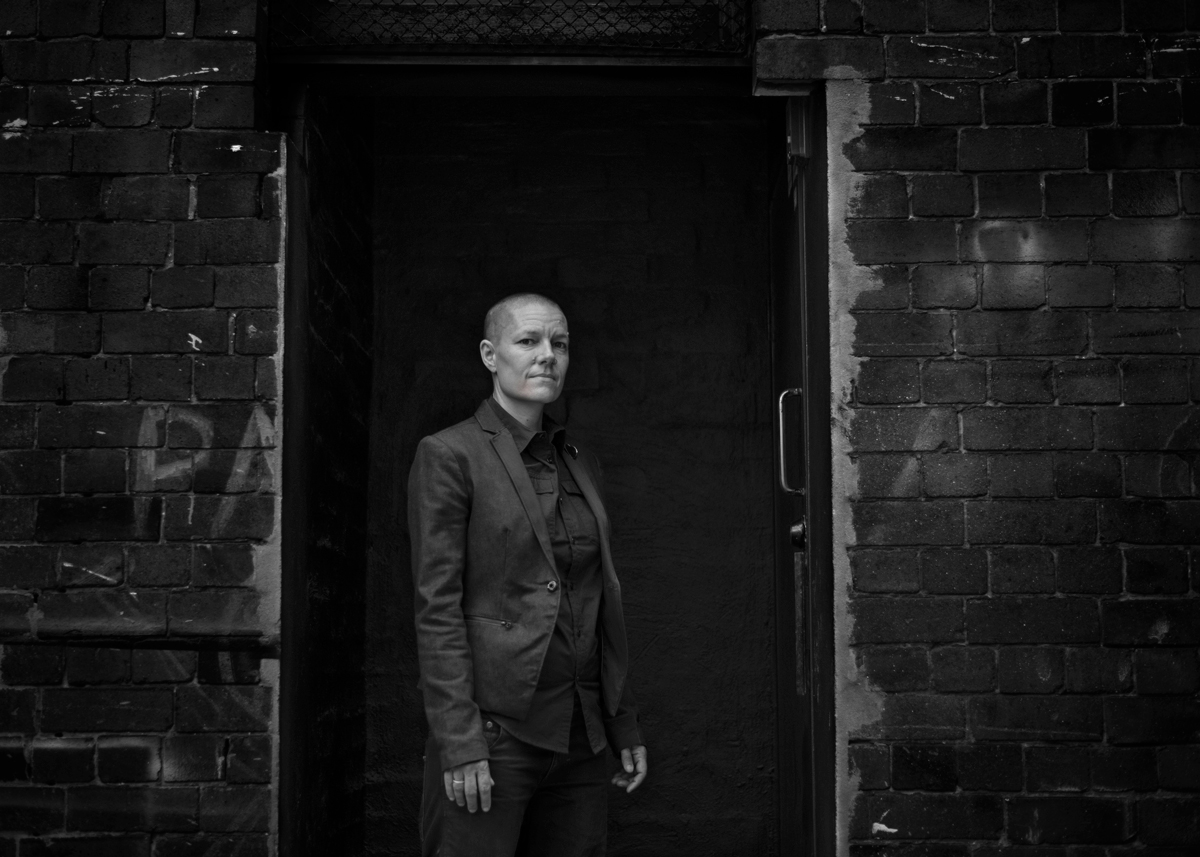

I decided early to dedicate myself to this method of self-education. My chosen masters were artists who offered an invitation into a world of their own making, creators of their own destiny. As the one and only Australian artist Dave Graney so beautifully puts it, I dig the pioneers.

As a young girl I discovered many of the female artists that I’m still inspired by today because they had amazing album covers with fabulous hairdos and long flowy or super short dresses with mismatched boots and clever or evocative titles (like Country Gold, Fist City, Tammy’s Touch), which was always enough to get me in (I’m shallow like that).

Country vinyl was also the cheapest in the bargain bins at the cool record stores, or the markets and the junk shops. And that’s how and why I started building my treasured collection of Dolly, Loretta, Tammy, Tanya, Jeannie C, Wanda, Sammi Smith records – and from liner notes learning more about who was who, watching out for particular songwriters who would appear often (I’m still obsessed with finding out about Lola Jean Dillon – anyone?), about who discovered/mentored who, discovering Conway Twitty and George Jones and Porter Wagoner from their duets with the ladies I loved. All the fascinating info I held in my head came from album covers. I spent hours transcribing lyrics and singing along.

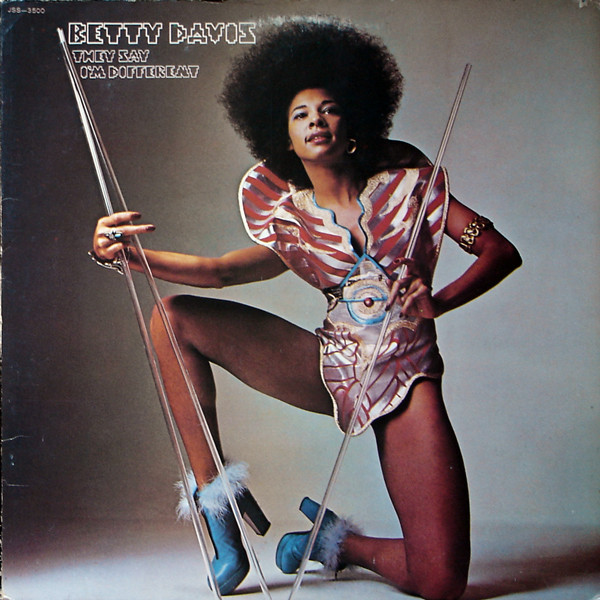

I was fourteen when my disco loving big brother bestowed a copy of Betty Davis’s record They Say I’m Different on me, and it was as though the world suddenly lit up and I knew my own possibilities were endless. Hey Lo, I reckon you’ll really like this record.

Good God! The young woman who adorned the cover wielding perspex rods on her knees in a funkadelic space suit simply blew my mind. And I wasn’t the only one – young Betty not only married Miles Davis in the late 1960s but was responsible for introducing him to her up-and-coming guitarist buddy Jimi Hendrix, which lit the fire under Miles’s ass that inspired him to head down a whole new direction with Bitches Brew – thus inventing jazz fusion. Thanks Betty!

But much more importantly to me, she wrote and produced her own albums – three of ’em – albums that sounded like nothing had ever sounded before. A rare feat indeed. She was an auteur of song. She was the sole proprietress of her own foxy, down and dirty sound, with incredibly groundbreaking songs like ‘He Was A Big Freak’, ‘If I’m In Luck I Just Might Get Picked Up’ and ‘Anti Love Song’. Miles Davis said in his autobiography “If Betty were singing today she would be something like Madonna, something like Prince…”

Betty was truly a musical expeditionist and you could hear it pay off in the genre-defying sounds she created. In ‘They Say I’m Different’ Betty sings about discovering Chuck Berry when she was sweet 16. About Lightning Hopkins, Bo Diddley, Big Mama Thornton, Leadbelly – about how her heritage is what made her who she is and that’s why she’s different, why she’s strange.

This moved me. I was hooked. I discovered that young Betty Mabry was a hit songwriter for acts such as the Chamber Brothers and The Commodores, a top model, a nightclub entrepreneur. That Jimi wrote ‘Foxy Lady’ for her. That apparently not a single minute of video footage of this remarkable performer exists, despite her few live concerts being described as outrageous, incendiary events, half the time getting closed down by religious groups protesting her ‘obscene’ lyrics. That Betty made her own stage costumes.That Betty finally decided the world wasn’t ready for her, after three albums that didn’t sell, and simply retired, leaving a tiny but ever growing legion of helpless, obsessive devotees in her wake, waiting breathlessly for a whispered-about mythical lost album to emerge.

‘They Say I’m Different’ is Betty Davis’s second studio album, written and produced by herself.

This patchwork of facts, the deliciously torturously slow gleaning of snippets of information was gathered over years from various unreliable sources, with each new fragment of information accompanied by a flicker of excitement. The lack of available information made me hungry for it. My Betty records were my prized possessions, and gazing at those album covers provided a portal into another world. If I ever happened across someone else who knew who she was, it was like we were instant soulmates, bonded by a love of the Queen of Foxiness. I called my first album Born Funky Born Free, which I recorded in my bedroom, as some kind of homage to Betty, and wrote a song from her imagined point of view called ‘My Friends Call Me Foxy’. Performing that song always makes me stand up a little straighter.

That lost album, Is It Love Or Desire?, has since been found, and it is, of course, amazing. Columbia have also put out a collection of unreleased tracks, and a Betty documentary should be hitting screens soon. I am still waiting with bated breath. I still get tingles when I get a new insight to who she was – via a snippet of studio dialogue on these new recordings that have finally seen the light of day in the digital era, or from the extensive, lovingly researched liner notes.

My brother’s gift of Betty Davis really encouraged me to search out the unknown, the pioneers, those that ran their own race, often without anyone cheering them on from the sidelines. It reassured me that those that flew their own freak flag were often those with the greatest gifts to offer the world, that popularity has never been a measure of talent and that as an artist it’s important to create whatever you damn well want and try not to let it break your heart if it takes an audience thirty years to hear you. Music has to be its own reward.

Digging deep to create one’s own musical journey rather than being spoon-fed what’s ‘cool’, what’s ‘underground’, who’s ‘influential’, is what serves as a true propulsion to musical invention and appreciation. In this bowerbird era of homogenized idolatry it can be hard to determine the genuine from the contrived. Regurgitation from reinvention. Today’s foxiness sometimes seems mere pastiche, learned, perfected, smoothed out. It does not move me the same way.

The endemic hypocritical nature of youth culture that can sport images of Che Guevara on T-shirts – yet live in an era that is terrified of terrorism is blatantly apparent. Revolution is now called terrorism. Doesn’t have quite the same ring to it. Music should shake you to your core, slay you somehow. It should fill the holes in your soul. It should take you places you never imagined and then take you higher – and then hold your hand in the dark when no one else will.

Seek your own masters and let ’em kill you…

Lo Carmen is a musician and actor. Her latest album is Lovers Dreamers Fighters. Below is a playlist Lo prepared to accompany this feature.