“Driver, let me tell you a secret.

A secret in the shape of a song”

– The Triffids, ‘Suntrapper’ (1987)

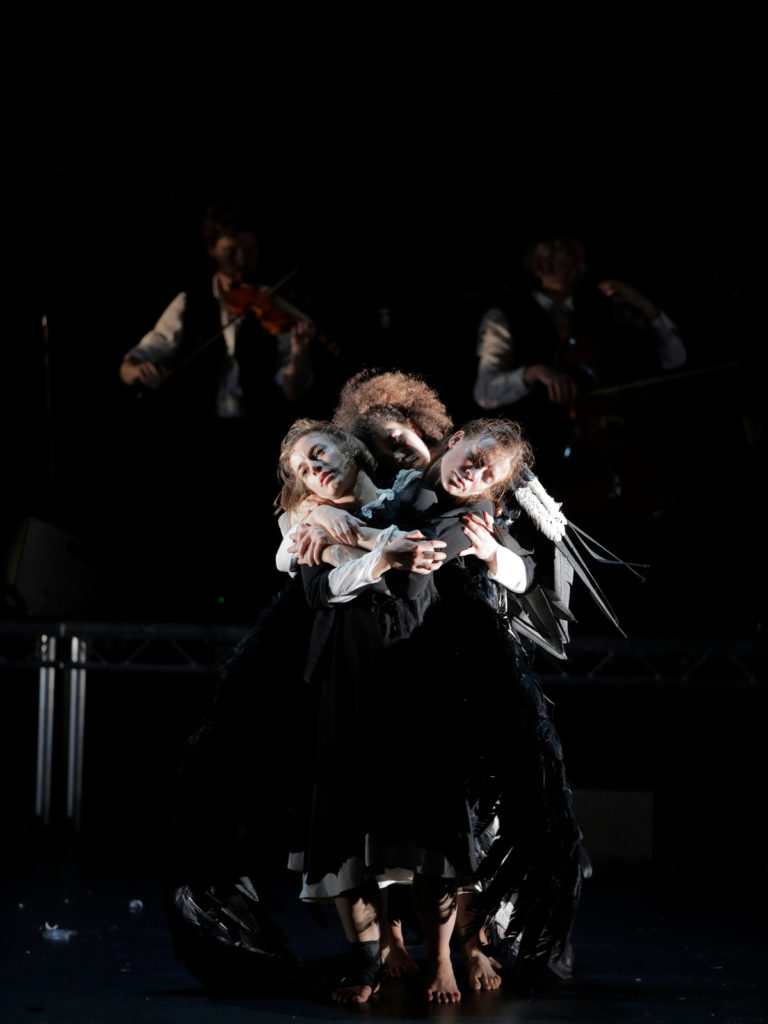

10. Louis Tillett & the Art of Darkness, Factory Theatre Marrickville, Friday 29 September

Louis Tillett returns for an all-too-rare show, touted as a 3-hour extravaganza with a 10-piece band, and with a new website that offers his music direct for whatever you’re prepared to pay. Tillett got his start with punk-inspired garage-rockers The Wet Taxis, though their origins as electronic experimentalists reveal broader interests. His music morphed into a dark blend of jazz, soul and R&B in sideline ventures like Paris Green – a loose improvisational combo that became a Newtown institution – and on his own superlative solo records like Ego Tripping At the Gates of Hell, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this November. Louis’s catalogue has a glowering but lyrical intensity, moving from moody minimal sketches on underrated albums like Midnight Rain to storming brass-fuelled epics like ‘Sailor’s Dream’ and ‘Condemned to Live’. Listen and read lots more on Louis’s site.

Louis Tillett, Linocut portrait. Image credit: Lucy Child.

9. Clan Analogue 25th Anniversary LP, Co-Ordinate: Collaborate Beyond the Algorithm

Starting in Sydney in 1992 but now a national endeavour with global connections, the work of Clan Analogue – Australia’s longest-running electronic music and arts collective – attests to two core values: a truly D.I.Y. spirit, and a forward-looking commitment to innovation, even when cannibalising the past for instruments and materials. For their 25th anniversary and 50th record release, the Clan invited 50 electronic artists to participate in the Co-Ordinate project, each collaborating with someone they’d never met before, in ways that explicitly contradicted their usual creative approach. This connected with the theme of the project, ‘Beyond the Algorithm’, which challenges the data-led herding of social media users with common interests into echo chambers of shared values, ultimately increasing conformity and group-think. The results on Co-Ordinate are hypnotic and eclectic, skipping across genre.

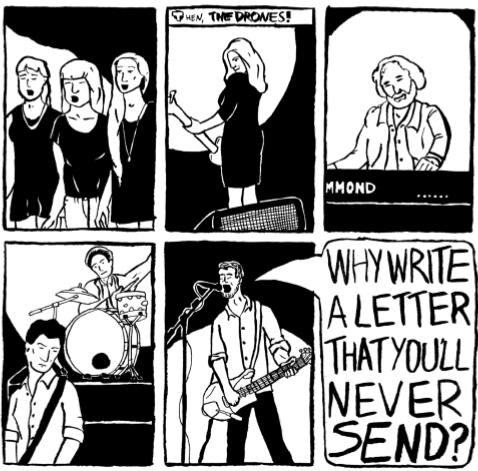

8. Beaches, Second of Spring LP (Chapter Music)

Melbourne’s psych-rock quintet Beaches are back with a remarkable third album to follow up 2013’s stunning She Beats. Second of Spring is a rare beast for this country: a double album of new original material, probably the first from an Australian female-led outfit since 2020 from electronic duo B(if)tek back at the start of the century (a highpoint of Clan Analogue’s discography btw). The stylistic sprawl of the 17 tracks achieves the paradoxical accomplishment of sounding like the best bits of lots of different bands and records without being overly derivative, stale or uninventive. That ‘Arrow’ reminds of Curve, ‘Mutual Decision’ of Fripp & Eno, or that ‘Grey Colours’ could be an outtake from The Cure’s Disintegration makes them no less enjoyable. There’s always been some pop sparkle mixed in with Beaches’ krautrock homages and instrumental wig-outs but they’ve added a large dollop of 4AD-style goth drama and twinkling shoegaze atmospherics to Second of Spring and the outcomes are very persuasive.

Beaches.

7. Chapter Music: Guy Blackman and Ben O’Connor

Beaches’ records are released by Chapter Music, one of the country’s best independent labels, which like Clan Analogue is also celebrating its 25th anniversary this year. Guy Blackman, label founder, and his partner in life and work, Ben O’ Connor, are not just patrons but genuine fans of Australian music; as eager to share the musical treasures they unearth or create as they are to support the efforts of so many others. Guy was invited to make a mixtape of Australian sounds this month for Noise In My Head on 3RRR FM and he responded with a set of rare synth-pop and post-punk, much of it set free from obscure cassettes and private press vinyl. I’d planned to feature Guy’s mixtape in this month’s column, and then I also read Ben’s open letter cogently explaining how the Same Sex Marriage survey is hurting ordinary gay Australians like him and Guy, so I thought that should be here too.

Guy and Ben, now and then.

6. 45th Anniversary of Allison MacCallum, ‘It’s Time’ (RCA, 1972)

Go back 45 years in time and the nation was embroiled in a different but still-divisive political campaign: the 1972 general election. Allison MacCallum was a Sydney singer who’d left a progressive soul band, Freshwater, for a solo career, hitting the top 20 in April 1972 with her debut single, ‘Superman’, written by Vanda & Young. She had a handful more hit singles that same year but the song she’s best remembered for was a complete flop, at least in sales terms. For while her rendition of ‘It’s Time’ – the Labor Party’s election campaign song – can at least partly claim responsibility for helping to elect Gough Whitlam and end 27 years of conservative rule, it didn’t trouble the charts in any state, perhaps because radio staffers or chart compilers didn’t want to support the ALP, or maybe because listeners were able to get their fill of the song from the ALP campaign’s saturation advertising across every channel.

5. Vale Charlie Tolnay (Grong Grong, King Snake Roost, Lubricated Goat)

The passing of guitarist Charlie Tolnay in Adelaide was announced mid-month with scant details, just that he’d had a brief and unexpected illness. Tolnay was a founding member of pioneering garage noise outfits Grong Grong and King Snake Roost, much revered by the likes of Jello Biafra, Jon Spencer and Mudhoney, and later an integral part of outfits like Lubricated Goat and Bushpig. Never as lauded as contemporaries like Rowland S. Howard or Kim Salmon, Tolnay’s technique was an unusual and unrelenting one, combining dirty blues, free jazz, and post-punk to sound like he was strangling multiple guitars at once. Trouser Press called his playing “thug-jazz” which sounds about right. He refused to get naked like his other bandmates during Lubricated Goat’s infamous performance of ‘In The Raw’ on ABC TV’s Blah Blah Blah, so we are forever spared YouTube footage of his “big hairy arse”, as he put it; instead try this incendiary clip of Grong Grong’s first ever gig.

4. The Sand Pebbles Pleasure Maps LP (Kasumuen) & The Woodland Hunters Let’s Fall Apart LP (Bandcamp)

The shared element for both of these bands is guitarist/singer Andrew Tanner, ex-Seven Stories, who you might remember from their 1990 album, Judges and Bagmen. The Sand Pebbles LP, their sixth, came out a few weeks back and is a strong contender for local album of the year, melding electronics and psych-rock with aplomb, revealing more nuances with every play. The vinyl LP is a thing of beauty, but damn it the CD features a stellar cover of ‘Oh Sweet Nuthin’ – decisions, decisions. The Woodland Hunters’ just-released Let’s Fall Apart has a ragged, country rock sound that has more in common with Crazy Horse or the Stones, rather than the Neu or Velvets’ records that inform their sister band. What both have in spades though are memorable songs with a delightful tendency to stretch out over time, with twisting guitar solos and extended instrumental passages that swagger into the stratosphere.

3. 50th Anniversary of Mick Bower leaving The Masters Apprentices

Back in September 1967, while The Masters Apprentices were enjoying another national top 10 hit with their psychedelic pop smash, ‘Living in A Child’s Dream’, the pressures of stardom had begun to take their toll. Mick Bower, guitarist and chief songwriter, had been exhibiting signs of exhaustion, culminating in a full-fledged nervous breakdown on tour in Hobart. After a catatonic performance, unable to move or play his instrument, he was sent home to convalesce. The band had to rethink their direction and go on without him. “We almost called it a day,” singer Jim Keays told me in 2012, “Mick was an amazing songwriter, the only person who was writing stuff like Mick then was Ray Davies.” Half a century on and things have come full circle, with Bower now back playing with some of the original band, paying tribute to the Masters’ songbook and their fallen comrade Keays, who passed in 2014.

2. Fallon Cush – Morning LP and launch at LazyBones, Marrickville on Friday 20 October

This Sydney band have released a handful of discs in the last six years, with 2016’s Bee in Your Bonnet the best of the bunch and the one you could fairly mention in the same breath as influences and precursors like The Jayhawks or Tom Petty. New album Morning is stronger still, and keeps to the point with just nine noteworthy songs in 34 minutes. The guitars ring out like Roger McGuinn in a belltower. The production is crisp but seasoned, with warm layers of keyboards and vocal harmony. Bandleader Steve Smith has a bright open voice with a slightly nasal twang, sounding a bit like George Harrison, if George liked singing You Am I songs in the back of Perry Keyes’ taxi cab. Morning is aptly named because it’s the kind of upbeat and melodic listen that’s easy to digest early in the day. Could it use a bit more piss and vinegar in the brew? Maybe, but then that’d make it a different record entirely.

1. Vale John French

I didn’t know legendary recording engineer and producer John French, who sadly died mid-month aged 75, but there’s a common theme being heard from those who did. You could start a conversation with him about some music, any music, from Australia’s distant pop past and he’d invariably say, “Yes, that’s one of my mine”, before regaling you with personal details of the session. Take a look at his Discogs listing, which while extensive is still riddled with gaps. French was chief engineer at Melbourne’s TCS Studios alongside colleague John Sayers, at a time when many recordings had no producer except the band, so the engineer shouldered more of the load. Let’s end this month’s column with a tribute to John French, a cheeky extra list of 10 crucial Australian LPs he helped bring to life, or at least made sound a hell of a lot better.

10) Not Drowning Waving – Claim (1988)

9) Weddings, Parties, Anything – Scorn of the Women (1987)

8) Billy Green – Stone soundtrack (1974)

7) Aztecs – Live at Sunbury (1972)

6) Coloured Balls – Summer Jam (1973)

5) Madder Lake – Stillpoint (1973)

4) The Dingoes – The Dingoes (1973)

3) Company Caine – Product of a Broken Reality (1971)

2) Various – Morning of the Earth soundtrack (1972)

1) Skyhooks – Living in the Seventies (1975)