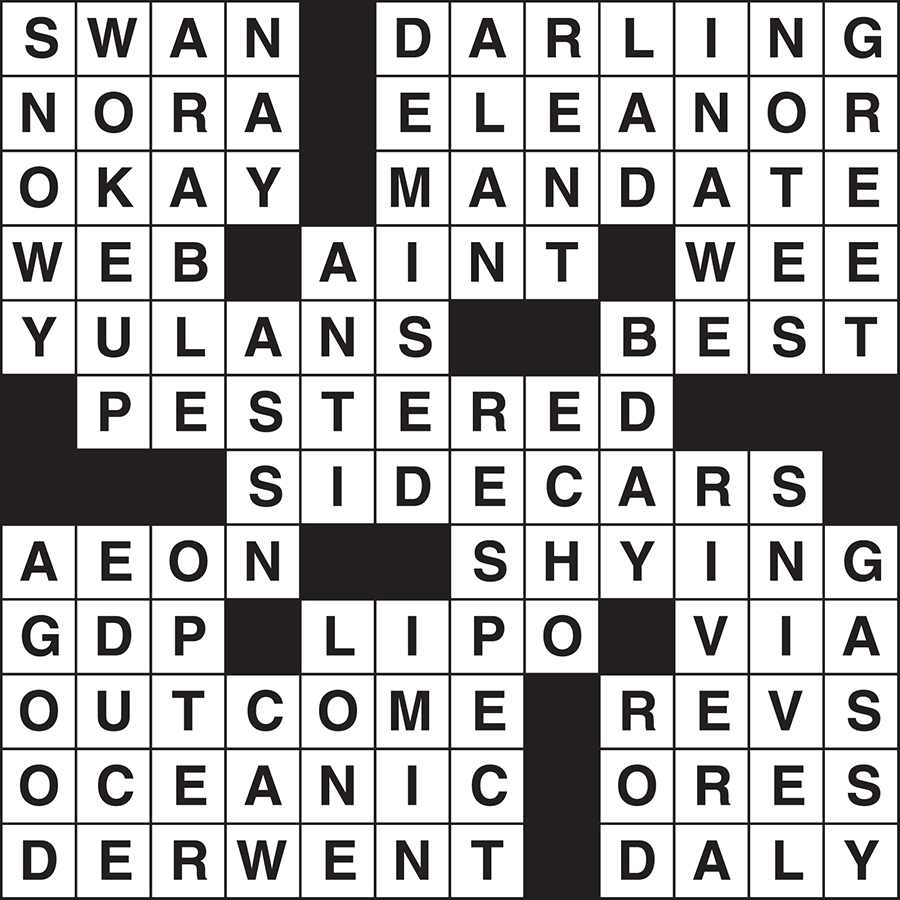

ACROSS: 1. Swan, 5. Darling, 12. Nora, 13. Eleanor, 14. Okay, 15. Mandate, 16. Web, 17. Ain’t, 18. Wee, 19. Yulans, 21. Best, 22. Pestered, 25. Sidecars, 28. Aeon, 31. Shying, 33. GDP, 34. Lipo, 36. Via, 37. Outcome, 39. Revs, 40. Oceanic, 41. Ores, 42. Derwent, 43. Daly.

DOWN: 1. Snowy, 2. Woke up, 3. Arable, 4. Nay, 5. Demised, 6. Alan, 7. Rent, 8. Lad, 9. In awe, 10. Notes, 11. Greet, 17. Anti, 20. Assn, 21. Bday, 23. Respect, 24. Echo, 26. Rivera, 27. Snivel, 28. A good, 29. Educe, 30. Opter, 32. Gassy, 34. Lone, 35. I’m in, 38. Caw, 39. Rod.

The June crossword was set by LR: twitter.com/LRxword

“Although the lights are fantastic and mesmerising, I find that the people are the real attraction. The visceral amazement from the face of a child to the serenity of the aged watching the crowd move by, this occasion is special to all that go.”

“She’s watching the rush of the faces / She’s getting to know what Sydney looks like in June.”

– Alex the Astronaut, ‘What Sydney Looks Like in June’

When northern Italian acquaintances meet they are physical about it; kisses planted on cheeks are stylish without being perfunctory like their Swiss counterparts across the Alps. They clasp arms and shoulders and pat backs with the contentment that, invariably soon, a carafe of modest but excellent local wine will accompany their flowing conversation.

When my wife and two small children and I crowded into a small restaurant in the town of Santo Stefano Di Belbo last European winter, on the edge of the provinces of Cuneo and Asti in Piedmont, we found a table in what was an empty restaurant with an open fire. Within five minutes the room was filled with blue overall-clad workers kissing and catching up. This was the lunch hour cacophony for the local Asti Spumante bottling plant adjacent to the town in the industrial North.

As Sydney embraces winter, it is nice to turn to a restaurant that is as familiar and reliable as a warm hug. On a crisp late May morning, I meet my luncheon companion, Sydney actor and sculptor Luke Storrier, with an outstretched hand – and am received with two arms around my shoulders.

We’re standing aside ‘table 1’, the small setting for two next to the bar at the Potts Point classic Fratelli Paradiso. The restaurant has become a veritable canteen for local creative industry types, attestable in the smattering of cocktail orders being taken around us. It seems today the only mixed drinks at lunch are ordered by admen and artists (a new form of AA?). I’m with the latter so we ensure a Campari with soda or two are on their way.

I wonder if my fellow diners, looking so naturally ensconced at what are certainly their regular tables, ever need glance at the menu scrawled on the wall. Why would they when I doubt it ever really changes?

I have known Luke Storrier close to a quarter of a century, which sounds less impressive when the first meetings were over Lego. Now a successful sculptor exhibiting with Tim Olsen, Luke is one of the more thoughtful among an impressive milieu of early career artists who have emerged over the last half decade in the city.

I doubt if I’ve ever eaten at Fratelli without a plate of their Calamari Sant’Andrea and so we promptly organise that and some crudo of cured kingfish with fennel and (bizarrely) jalapeno to accompany a couple of glasses of Italian white. The wine list is an unpretentious mix of very decent and not wildly expensive Italian wines – with a splash of off-the-beaten-track Australians. I’ve always believed the key to a local eatery’s longevity is to be found in the ability of their sommelier and owner to contain their greed; Fratelli hits the mark with only one or two ‘investment banker’ priced wines.

The food is delicious but simple enough that none of the waiters fuss over it, allowing us to catch up as the entrees are replaced with our pasta course, a tagliatelle ragu, the texture of which I’d compare favourably to most I’ve had in the Emilia Romagna city that gave its name to the sauce, Bologna.

Food on ‘the pass’ at Fratelli Paradiso. Photography by Lyndal Irons.

This year’s Chelsea Flower Show has just finished in London and I’m curious to hear from Luke what it was like to be part of Charlie Albone’s 2015 presentation at the prestigious London competition. His response is along the lines of “enormous fun, not as lucrative as expected” which is basically the experience of everyone who has ever tried to do business in London.

This gets us to the other competition currently on in Sydney, the Archibald Prize. The ‘face that stops the nation’ has played a big part in our lives: Luke’s father has won it as an artist; my father, as a sitter, was a serial loser. We both intensely love and hate the annual beauty parade. But the role it plays in Australian art history is without question, a barometer to measure trends of the day. Far more often than not, the right painting is chosen by the board of trustees.

We discuss an issue with this year’s broader selection (both of us were happy enough with the winner) that so many of the portraits had the same feeling as one another; that there was a lack of variation in the expression being employed by the brushstrokes or compositions of the various finalists. Is this a by-product of the Instagram age?

Today artists are far too quick to post studio photographs to the world at large, using them as their own approval guide before showing their dealer (how can a dealer complain if there are a thousand likes?) – indeed who needs a dealer? Many artists now sell directly using this medium. It is too early to judge this, and both of us, also users of the platform, can’t blame Silicon Valley if Sydney artists in their late 20s and early 30s all look like mere shadows of each other.

A kilogram of grass-fed black angus T-Bone arrives in front of us. With a good deal to chew over, it is fitting we bitch about the Wynne Prize, supposedly awarded to the best Australian landscape painting (or sculpture). I’ve always thought it’s a bit like an Agricultural Society awarding a ribbon for the best Angus bull (or alpaca) in show. There should be a separate prize for sculpture which would give both it and landscape their due respect.

The mountain of meat we washed down with a pretty excellent bottle of Italian red should have finished us off. But we order a tiramisu – if only to act as table decoration and to make us feel better about the grappas we swig as we face the prospect of going back out into the cold. At least neither of us has to return to an Asti Spumante bottling plant this afternoon. Then I remember the last sculpture of Luke’s I bought was a small construction of a wrapped bottle, and I smile and order us both one more for the road.

Entrées: Calamari Sant’Andrea – $25; Crudo of cured Kingfish, fennel, jalapeño, basil emulsion – $24. Mains: Tagliatelle ragu – $27; Fiorentina O’Connor black angus 1 kg – $94. Sides: Salad – $12; Potato – $10. Drinks: 2 Campari soda – $28; 2 Glasses of Ronchi Di Cialla Friulano – $30; 1 Bottle of Erbaluna Barolo – $Investment Banker.

Photography by Lyndal Irons.

I have had a duck fetish since boyhood. I used to play a role similar to that of a caddie when my father went duck hunting. We lived at Colac in the lakes country of the Western District in Victoria. My father was President of the Gun Club so our years were divided into the various game seasons for quail, ducks and hares. We also shot rabbit and swan as well as other feral animals that were annoying the farmers, like pigs, cats and wild dogs. They were different times.

The prize game however were the first three, all rating equal on the gastronomic charts. The ducks and quail are native to Australia. They fly down from Asia to breed on the fertile volcanic banks of the lakes and in the harvested fields of wheat. The ducks feed on the aquatic micro-fauna and the quail fatten up eating the grain left on the ground after the passage of the harvesting machines on the plains.

But it was the duck shoots that presented the greatest challenge. The ducks could recognise the outline of a shooter and his gun at a glimpse, the flock would be warned and escape from the area with discipline and haste, not to return for hours. This problem was solved by the hunters building hides early in the season and then arriving before sunrise for the morning shoot. The other indispensable aids were a flask of King George IV scotch whisky and a well-trained gun dog to gather the wounded quarry from the lake after it had been shot.

The killed ducks were divided according to need and the hunters returned in triumph to their homes and families smelling of gunpowder and marsh. They cleaned and plucked the birds ready to be cooked (the nasty work was all done by the men!), feeding any unwanted remains to their dogs. The guns would be cleaned and packed away, ready for the next shoot.

Duck became a family luxury to be enjoyed for Sunday lunch or for dinner with valued guests. The favourite dish of ours was ‘Wild Duck Oporto’. A base sauce was prepared from the carcasses. The bones were browned with mirepoix, herbs and spices, including some juniper berries, and a 50/50 mixture of red wine and port to make the lightly thickened sauce. The meat was gently browned in a skillet and then cooked at a slow simmer in the sauce. Wild mushrooms picked on the shoot would be added to the sauce to create a rich dish heavily perfumed with the gamey aromas of the duck. Served with an aged decanted bottle of Penfold’s St Henri, the guests would be blown away.

It is of course illegal for protected species of game, which include wild duck and quail, to be sold. The same is true of ortolans in France. Even so the best gourmets seem to have enjoyed them prepared by their favourite chef. Michel Guérard told me that chefs are not ornithologists and that they may occasionally mistake ortolans for quail, as his sous-chef did with our table one time. The guests, like us, are generally very forgiving and ignore the mistake, even though the ortolans are distinctively smaller and recognisable to those ‘in the know’, commes ils dits!

The most common wild duck are the Brown and the Muscovy. Jill Wran, wearing her farmer’s hat, breeds Muscovy ducks, with their dark red flesh for which the au porto method works perfectly. But I know of no one who breeds brown ducks. The other ducks that are commercially available are the white Pekin duck from Luv-a-Duck which supplies the major supermarkets. My commercial choice would be the Grimaud Duck available from Game Farm at various farmers’ markets around town.

The Pekin duck is perfectly suitable for most Asian preparations. It is easy to roast (1hr15mins at 170 deg C.) and it will feed a family of four to five easily and cheaply. Remember to save the fat – a sauce made with white wine, a little balsamic vinegar and some black olives or fig will make a splendid dinner with very little trouble.

Duck fat is not only healthy, it is low in triglycerides and has a high burning temperature. You should use only duck fat when sautéing potatoes as they colour up perfectly. The Pekin duck has a lot of fat to meat. This crisps up the skin perfectly for Asian dishes like Pekin Duck, but it is perhaps less suited for braising.

Famous restaurants that specialise in duck include the very grand La Tour D’Argent in the centre of Paris. La Tour roasts Muscovy ducks rare and then uses a silver press, not unlike a small wine press, to extract the blood and juices from the carcass. The sauce is made with the extract and some fine Cognac. The restaurant numbers each carcass individually and presents a card with the number to the guest. They are currently up into the second million of ducks used over the last 100 years!

Beijing has its share of ‘duck’ restaurants including the Sick Duck, the Wall Street Duck and the Quianmen Roast Duck – where the standard meal was ‘Four Ways Duck’ writes Nina Simonds in her book China’s Food. This dish featured cold stuffed duck neck, roasted duck, vegetables cooked in duck fat and a duck soup. Today the menu offers over 200 dishes using every conceivable part of the bird.

The Grimaud duck is the best one for simple roasting and braising. It has a higher ratio of meat to fat and the breast is double the thickness of the Pekin duck and more suited to grilling. A show-off dish is to have the breast grilled medium rare and the leg and wing braised, perhaps in the port sauce. The pink flesh of the breasts contrasts beautifully with the deeply coloured sauce.

The other preparation I would like to mention is preserved duck, Confit de Canard, the great dish of France’s south-west. In this area, most ducks are bred for the fattened liver, the foie gras. The meat is almost a by-product of the foie gras industry. The confit is a way for the farmer to preserve meat for the winter. The leg is heavily seasoned with grey salt, black pepper, thyme, marjoram and bruised garlic cloves. It rests in this mix for two days before being wiped clean and then cooked in duck fat at 80 deg C. for six hours. It is then packed into preserving jars, covered with the melted fat and refrigerated. The confit is simply grilled or included in the classic dish of the area, Cassoulet.

I often view with evil intent families of ducks walking towards the ponds in Centennial Park. I dream of ways to entrap them so I can once again experience those rich, delicious dishes of my childhood.

Portrait of Tony Bilson by John Olsen

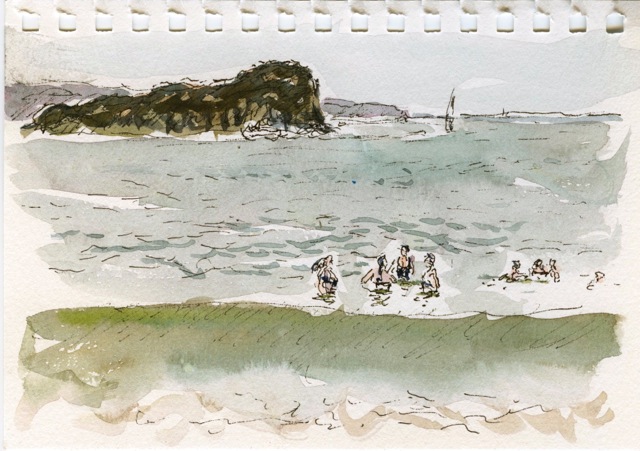

Saving our knees, we stepped cautiously down the track through the casuarinas. The gradient was steepest here – sand and smooth rock covered in a slippery carpet of umber fir needles. The five children had already gone ahead, lithe and confident, racing each other to the bottom. We, the adults, were carrying the picnic food, towels, and swimmers.

On the last fifty metres of descent, where the sickle-shaped beach finally comes into view, our son Felix came running back up to us, breathless.

“There’s a big lizard down near the water, with a tin of cat food stuck on its head!”

We followed him, going left along the rocky shoreline of Broken Bay, to where four children stood around a large goanna, which was almost camouflaged on a flat slab of pocked grey sandstone. There was a yellow and black tin can sitting on its head – Black & Gold Seafood Platter Cat Food. The label was still bright, so it couldn’t have been in the sea for long.

Our muscly friend Geoffrey crept up quietly from behind and threw a big beach towel over the goanna’s body. Before it could shake itself free, he lay gently but firmly on top. From the other side, I took hold of the jerking head and held it still. Somehow the lizard remained calm; in the dark, being manhandled by unknowns.

Looking closely, I saw that the metal of the can had been cut with one of those claw-shaped openers, making a circle of jagged triangles. Someone on a cruiser or houseboat must have opened it for their waterborne cat and tossed it into the Hawkesbury. There were specks of blood next to each sharp point. My first tentative tug at the tin sent the lizard’s legs into a spasm and Geoffrey had to hang on like a rodeo rider. I tried again, gently, and after five anxious minutes, by pressing my fingers against the flesh near the sharp bits of tin, managed to prise the can free.

I jumped back, thinking that the goanna might snap at my hand, but it stood there motionless, blinking at the sunlit water. At last, it came to life and scrambled into the dry mulch under the casuarinas. I picked up the tin and put it in my bag.

Excited by this event, the children ran off down the beach to where low tide had revealed the crown of a rusted engine block, from a wrecked fishing boat. They spent an hour trying to dig it out, before they got hungry.

2013: Bathers, Flint and Steel, watercolour and pigment on paper. Artwork by Tom Carment.

There must be something about West Head that encourages such Sisyphus-like activity. In 1959 two park rangers heard someone digging, off the main road. It was Kevin Simmonds, the famous prison escapee, excavating a hole to secrete a stolen caravan. He tied the unsuspecting men to a tree, apologised, and stole their ute, continuing his flight from a force of armed pursuers. Simmonds was a handsome and charismatic young man who attracted a lot of public support as he evaded capture for nearly a month. He was caught in the bush near Kurri Kurri and, six years later, was found hanged in his cell at Goulburn Gaol.

The idea of burying a caravan in the bush of West Head to hide from pursuers captured my boyish imagination. I imagined it with a periscope. These days, knowing how hard and rocky that country is, the idea of digging a caravan-sized hole out there seems absurd.

Apart from a few settlements on its southeast shore, at Mackerel, Currawong and Coasters Retreat, accessible only by water, the West Head peninsula was saved from housing and development. It had strategic military importance – a big gun at its eastern end protected northern Sydney from naval attack.

There was once a single house with a tennis court at the western end of Flint and Steel, demolished in the late 1960s; and I met a woman on the track ten years ago who told me that as a child she’d lived in a cave halfway down, above the casuarinas, with her father. She showed it to me: a three-sided space, its dry sandy floor covered in lizard prints.

West Head was a place of great significance to the Guringai people, who created galleries of engravings on many of its smooth sandstone rock platforms – figures, shields, animals and fish. The making of these would have required incredible patience and labour – millions of small chips, rock on rock, an incremental linear progress, following a design best seen from three metres above the rock.

In my search for good painting spots I have several times stumbled across engravings of fish, small and large, and I have often found myself on the shoreline, sitting down beside shell middens.

I have wondered if the whole of Sydney was once equally covered in engravings and middens, and whether this peninsula is just a last untouched remnant of the whole.

Since 1975 I have walked all of the tracks on West Head but Flint and Steel remains my favourite. It starts from a grove of banksias near the eastern end of the West Head Road and winds down through one and a half kilometres of rocky bush to the water. There are angophoras near the top, and, at about halfway, a patch of palms in a small cleft of semi-tropical rainforest. All the way down you see jigsaw-shaped patches of water through the trees and beyond the rocks. I’ve seen this track burnt out by fires, damaged by storms, pink with wildflowers, and, more recently, invaded by tobacco weed.

On weekends when I’d ask our children, “Would you like to go for a bushwalk?” they’d always reply, in hopeful tones, “Flint and Steel, Dad?”

I guess it was a walk with a proper destination; a protected beach where you could swim, piles of driftwood to make shelters out of, creek water that snakes across the sand, perfect for earthworks and dams. There are circles of dried rock salt to sprinkle on your boiled eggs, and, when it rains, small caves in which to take shelter.

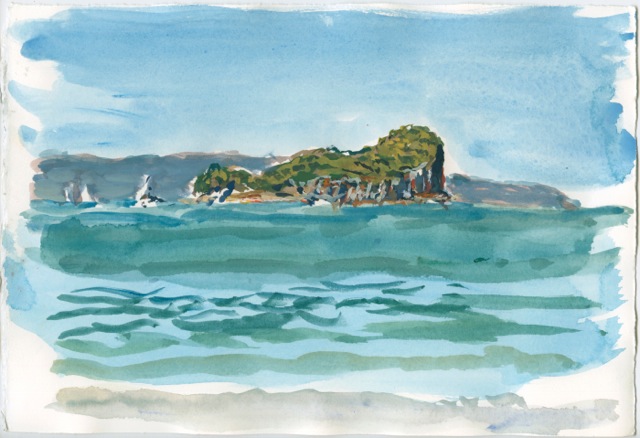

If my oldest son just wanted to lie in the shade of a banksia to read his fantasy novel for hours, no one would hassle him. Sunscreen and a swim were almost the only compulsory things. And the view out is wonderful – Lion Island, sitting in that large body of water, which moves from river to sea.

2017: Lion Island, gouache on paper. Artwork by Tom Carment.

Flint and Steel has a constant supply of fresh water too; a spring-fed creek, in a small cove three hundred metres along the rocks to the east. There’s a channel carved in the sandstone, long ago, by seafarers I assume, to ease the filling of barrels. These days, for fear of Giardia and other microbes, I zap the water I collect there with my battery-powered SteriPEN – easier than boiling it. No matter how dry the weather, there’s always fresh water trickling across that rock.

At breakfast one morning, my daughter Matilda, seven years old then, requested a day off school: “I want to go to Flint and Steel to paint with you.” It was nearly the end of the school year when they were mainly watching videos, so I said, “OK, sure.”

Two hours later we were sitting in the morning sun on the sloping rock above Broken Bay, side by side, painting pictures of Lion Island. After an hour or so we packed up our paper and paints, went for a swim and ate our salad packs and vegemite sandwiches under a banksia at the edge of the sand. On the drive home we bought a Christmas tree. Matilda said it was a perfect day.

In the casuarinas, on our way down to the water, an echidna had slowly crossed the track in front of us, like a good omen.

Tom’s favourite things for a bushwalk: Hat, Camelbak water bottles, woollen socks, SteriPEN, strips of old bicycle tube (for tying things on), contact cement (for when your boot sole peels off), a bag of pitted dates, Schmincke watercolours, small sheets of good watercolour paper, two sable brushes, a pigment ink pen, a small notebook and a pencil (for good ideas you get when walking).