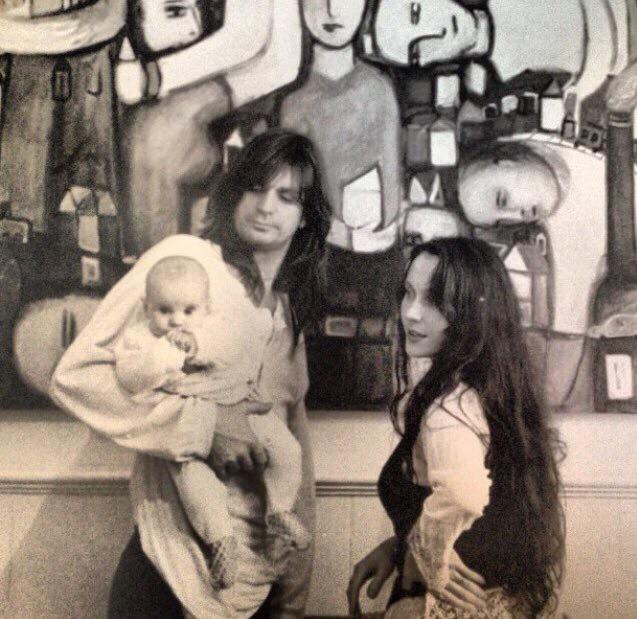

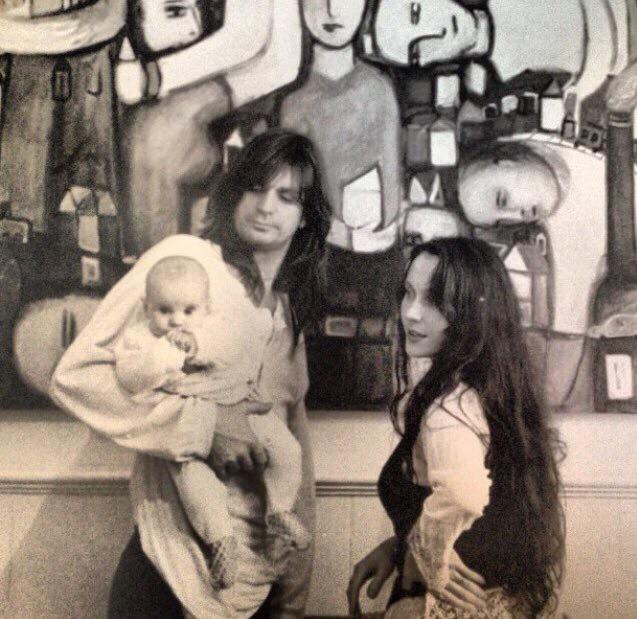

In the photograph, my parents stand opposite each other. I’m tucked into the nook of one of my father’s arms – a tiny bald-headed baby, eyes wide and staring straight ahead at the camera. They are both longhaired. My father is tall in jeans and a billowy shirt; my mother is much shorter, wearing a vest and a lacy Victorian blouse that buttons at her throat and cuffs around her wrists. She has one hand on her hip, one eyebrow slightly raised, lips parted as if about to speak. My parents don’t look at each other or at the camera – both their faces are turned towards me.

Behind them is a large canvas covered in a crowd of painted faces, figures looming over chimneys and cradling tiny houses in their arms. The photo is in black-and-white, but I imagine the colours of the painting are the same rich, earthy tones that characterised my mother’s work during that period: ochre, blood red and brown, blue skies in the background as dark as an oil slick.

Taken by a photographer friend at my parents’ home in Melbourne ahead of an exhibition of my mother’s work at the William Mora galleries sometime in 1990, it is one of the only family portraits I have of the three of us together during the two years after my birth that my parents remained a couple. In most of the photos from my early childhood, I am either alone or with my father, my mother always preferring to be behind the camera rather than in front of it.

My parents separated sometime between my second and my third birthday. I have no memories of them together. Instead, I have artifacts: songs my father wrote about my mother; an angry letter my mother wrote to my father across a primed canvas and later covered over with an oil painting. It now depicts a band of men holding old folk instruments – a drum, a flute, a mandolin – and one man with his head bent over a table, next to a bottle of wine. In the corner, a bare-breasted woman stands in a straw-yellow skirt, holding a red ball. If you look closely, you can still see the outlines of the red-paint letters showing through the dark background. For a long time I was a daughter-historian, trying to excavate my parents’ love and understand the loss of it.

After my parents moved to Sydney – separately – when I was five, I lived predominately with my father until I was 11. During those years, my father was a solid, dependable figure. He had been, among other things, the singer in a visceral, three-piece punk band for roughly ten years on and off by the time he met my mother. A few years after I was born he quit touring so he could sing me to sleep at night and be there when I woke up in the morning. By the time I started school, he had a regular job cutting patterns for stained glass windows and soldering them together with lead. He only played music at home.

My mother remained more elusive. She smoked Marlboro Reds and drove old cars that always broke down. Many of my childhood memories of the weekends I spent with her involve waiting on the side of the road with our dog while she called the NRMA from a payphone to come and tow us home. She wore red lipstick religiously, leaving a kiss print on all the take-away coffee cups left in the cup-holders of her beaten-up cars. She was never on time to pick me up. Her house smelled of cigarettes and turpentine, and I loved her with that special love girls reserve for the women they aspire to be like.

Growing up, I thought my mother was the most beautiful woman in the world and I didn’t understand why she hated having her picture taken. Of her wedding to my father, there were only a few candid photos. My uncle was supposed to be the official wedding photographer, but in his nervousness, he forgot to put film in the camera. Sometimes I think my mother may have been secretly glad – on her wedding day she was 25 and pregnant with me, and she also had the mumps. These factors aside, I’ve never known her to be happy with a photo of herself.

Maybe because they were so rare, the few photos I found of my mother, especially from when she was younger, before she was my mother, held a fascination for me. She’s never organised her photographs into an album – instead, she keeps them in wicker baskets or boxes tucked under the bed or inside her wardrobe. On my weekends at her house, I would shuffle through them, tracing the pictures of her like blueprints for the kind of woman I wanted to be.

‘Girl with crown’, 1997, Amanda Meares.

I also looked to my mother’s paintings for clues. Across her body of work are a collection of recurring images: figures wearing crowns, chimneys, houses with red pointed roofs, the red ball, cars, dogs, bridges, a red balloon, guitars. Intimacy between people in her pictures is rare. Her large oil paintings from the 1990s often depicted crowds of people towering over the surroundings that are supposed to contain them. Smaller canvases or watercolours focus on one figure alone, and there’s an introspective quality to these works I have always related to. One of my favourite pictures of hers is a watercolour I found buried in a set of drawers at her house earlier last year. It is a small work on paper depicting a black-haired girl sitting on top of a house on a hill, holding a dog on a leash, while planes fly overhead against a background of chimneys. “It’s me and it’s you,” she said when I showed it to her.

During the time she painted it, we lived in a Sydney suburb recently built out of an industrial wasteland. Planes flew low above the flat-roofed houses. Our home – one of six historic terrace houses on a street of warehouses – was opposite a plastic bag factory. At the end of the street was Sydney Park, a former brickworks and landfill site framed by major highways, now covered over with grass and a reservoir, smokestacks left behind like a crown for the rolling green hills.

There has always been an emotionally autobiographical element to my mother’s paintings. She’ll point to a work and tell me a story about that time in her life – that’s when your uncle moved out of our home and I lived in the country; this is a painting I did when your dad was on tour and I was lonely; that’s a picture of you and me when you were little.

But her work doesn’t just represent her world; it also transfigures it. The images in my mother’s work – industrial, domestic, symbolic – create their own language. In this way, her art acts like memory; it takes her experiences and collapses the specific details, rearranges them, and moves them into a realm of poetic gesture. Like Joan Didion’s notebooks, my mother’s art is her way of keeping in touch with the people she used to be.

I was ten years old when my younger half-brother was born. Five years later, a second brother followed. Although we were born from the same artist-mother, the weight of her two roles shifted after they were arrived. Evidently, raising two young boys with my stepfather is different than being a young, part-time single mother. For the ten years when my mother had a small child at home, she stopped producing the large-scale oil paintings I’d grown up around. She dyed her hair blonde. She bought a practical car. She went out to school assemblies instead of concerts. During this period, her work also changed. Instead of the large, bold and dark oil paintings, her art became more intricate and illustrative. She worried that fumes from turpentine would affect my younger brothers, so she switched to watercolours, acrylics and drawing. Many of her symbols remained the same, but the palette grew lighter – vibrant blues and rich greens, bright reds. For a few years, I hardly saw her paint at all.

I was a teenager then, living with her full-time after my father moved back to Melbourne. Starting to make my own work for the first time, I was going through a self-important phase, when I believed art was the most important thing of all. I felt frustrated that my mother, whose work I loved and admired, was not pursuing a career as an artist. It took me a long time to understand that she makes art for herself – for the sake of her own self-expression and satisfaction – not for validation. This is something I am still learning.

What I also didn’t realise is that this was also a period of stability for my mother, and her early work was a product of pain, of loneliness. Emotional excess whittled into art – this is something she taught me. Make work, she told me repeatedly at different stages of my life, because then you’ll never be lonely. A woman needs to be able to spend time alone and be okay, because that’s what keeps you from settling for less with men.

It is the women in my family who have always carried the line of visual art. From 1984-1987 my mother studied painting at Victoria College in Prahran, Melbourne. Her stepmother, my grandfather’s second wife, had been the head of the printmaking department there after gaining prominence in the Melbourne abstract art movement in the 1970s for her series of “dot-screen” paintings, compositions that featured bright washes of colour overlaid with a grid of screen-printed dots. These works combined the dual forces of abstraction: expressive gesture and geometric patterning.

My maternal grandmother was also a working artist. She supported her three children, of which my mother is the middle, by making jewellery and teaching out of her home studio as a silversmith. She used soft red wax to mould shapes from the natural world – bees and insects, snails, shells, knots of rope—and cast them into wearable pieces of silver and gold.

For these women in my family, art wasn’t “out there” in the external world – it was created in the domestic space, inseparable from everyday life. This is most true of my mother, who still prefers to work in the middle of the house.

Two years ago, my family moved to a bigger place in the Sydney suburb of Marrickville and my mother took out her paints again. A few years earlier, my grandmother had died, and my mother gathered up all of her tools and started making jewellery. She has her easel in the living room now, overlooking the Cooks River. We once lived on the other side of it, back when it was just the two of us, and we walked our dog around the water on the weekends. It is, and is not, the same river – restoration projects in recent years have cleaned it up. And she is, and is not, the same mother.

She paints by the window, looks out over our chickens and orange trees, the neighbours’ olive tree branches, to the bridge over the river, the lights of Sydney Airport beyond. Our dining room table is covered with paintbrushes, my brothers’ homework, pieces of Lego, laundry, orange peels, unopened mail.

The first time I saw her sitting there and working I almost cried. It was an image from my childhood I’d carried around with me for all these years, a memory before memory of my artist-mother. As a small child, I always had trouble sleeping, but she would let me stay up late with her. We’d sit side-by-side in the living room together, painting. She always left her paints out and let me use her good materials – the little coloured squares of her watercolour palettes, the chalky pastels that stained my fingers and were stored in a wooden box with a gold latch, each in a separate compartment like candies in a chocolate box. The only rule was that I had to wash my brush the way she taught me, swishing it in water and wiping it dry on pieces of newspaper.

‘Seesaw’ painting, 1987, Amanda Meares.

Although I recognise now I have no skill for evoking feeling through visual gesture – it’s like a language I love the sound of but can’t communicate in – childhood was a time I felt free to play without reservation or restriction. I loved to paint back then, in those late hours when we were alone, my mother and me, at work in a kind of serious and introspective play.

I’m sorry I haven’t got dinner ready, she said to me when I came over that day. When I’m working, I forget about food. That’s why it’s hard to paint and have children – you forget to feed them.

I felt exactly the same about the days I spent writing. Though I didn’t inherit my mother’s gift for painting, many people have commented on the kinship between my writing and songs and my mother’s work. Neither of us can figure out exactly what it is, but it seems to carry the same soul.

In recent years, watching my brothers grow up, I’ve started to attribute the creative passions we all share to the way my mother has fostered them. As children, we were never told to put our things away – we were free to pick up and play with anything, at any time. Our house, consequently, was and still is chaos – but it is a creative chaos. I realise now that child-rearing is just another creative act for my mother – that she considers her children as part of her body of work, alongside her paintings, cards, drawings on the backs of envelopes, jewellery hammered by her own hand.

I don’t remember the first time I knew what ‘art’ was, but I do remember my first image of an artist. Art was my mother. It was cigarettes and turpentine and tiny perfume bottles, broken-down cars, paint and ash and pastel, dogs and children and love and loneliness, passion and pain. To this day, the women I admire most are artist-mothers, who are able to create with pleasure and abandon but simultaneously raise children with the selflessness that requires. They live in two worlds, both nurturers and creators.

1990: Steve Lucas and Amanda Meares with baby Madelaine, photo by Tamsin O’Neill.

This story originally appeared in Catapult on 21 June, 2017.