Working in commercial hospitality is hard. There’s a lot of bullshit about how wonderful seasonal produce is, how creative the plates are, and how inviting the atmosphere is. What lies beneath those aesthetic concerns is immense amounts of labour, often done by people who will never own the means of production.

The vast majority of chefs, waiters, kitchen hands and sommeliers will only ever have their labour to sell to others higher up the food chain. The industry depends on an endless stream of people who need the work, but couldn’t imagine anything worse than a career at the stove or on the floor.

Hospitality is defined by host/guest relations. It’s also a practice that occurs in the private and social domains, which accounts for why so many punters get weird at cafés, restaurants and hotels. There’s something primal, something about how Mum and Dad did it, which unconsciously spills into the commercial domain. Much of the romance of food is generated by people with idealised versions of what their childhood meant in relation to their present. Their little version of the hospitality industry becomes Rosebud; a paid-for nostalgic rendering of what unconditional hospitality looks, tastes and smells like.

As children, if we’re lucky, we get served. It’s pretty much a one-way deal. Our parents (or carers) cook, clean, serve, nurture and encourage our bodies and self through our early years. They do so in the hope of hosting a person sufficiently able to care for themselves as adults. Sometimes, things don’t work out that way, and the adult-child stays home because it’s hard out there, and what makes it hard is doing the labour necessary to provision hospitality for oneself, let alone provide for a family.

Ironically, there are many people in hospitality who come from broken, dysfunctional homes. There is not so much nostalgia as resentment – and a yearning to forget. Churning out beautiful plates of food in an environment designed for pleasure becomes a consolation; a ‘this is how it should be done’ statement that seeks redress for the lack of nourishment they received as children.

If we don’t eat we die. Our bodies need energy to feed what biologists call the life-force – the force that ensures we never stop aging for a moment of our existence. That driving force, which compels our bodies through a quantum of lived experience requires energy to fuel it, and we fuel it by eating and drinking. Nutritionists settled on 8,700 kilojoules per day as the amount of energy our ceaselessly aging bodies require to go about our business. The kilojoule count is negotiable, which is lucky, but not by much if we aim to do anything other than obsess about how thin we are. Thankfully, we need less as we get older because life becomes more about decay than growth.

Reducing food intake to kilojoules and hospitality to host/guest relations is unromantic. Understanding the lawful minimum wage in Australia equates to $18.29 an hour (before tax) is hard-boiled fact, as is the reality that many restaurants and cafés don’t pay their workers penalty rates despite a surcharge for weekend and public holiday trading. When multinational companies like KFC have the front to tell the recent Senate Committee they haven’t paid weekend penalty rates for years and don’t aim to despite the law, it’s easy to understand why your local squat and gobble doesn’t either.

Valorising the production and consumption of food and hospitality practices has seen Australia develop a sophisticated, world-class hospitality industry. That’s a wonderful thing and worth celebrating. But the Victorian-era upstairs-downstairs relationship between workers and guests lingers in ways that should disrupt just a fraction of the multiple pleasures the industry provides us with.

So, next time you’re at your local, don’t be a weirdo, and spare a thought for the human beings on minimum wage, playing host.

Curious things, words. Most pass unremarked. Like spores in the wind they slip from the lips to shrivel and die on barren ground. Or spawn stunted slogans, the thistles of rhetoric, weeds of cliché. It wasn’t always so.

In times gone by there were whole forests spreading out and covering these plains, supporting an amazing diversity of word life. You’d walk through these massive book shelves into great thickets of poems, stories, essays and songs; a profusion of styles, a teeming, tangled riot of language – bawdy, comical, beautiful, wrenching and at times inflammatory, sparking raging fires of debate.

But the most impressive things in these forests were the old-growth novels. Towering tomes, chapters thick, they dripped with a rich and strange array of ideas. My Grandfather told me of this one – Russian, I think – soaring up from the forest floor above a canopy of pamphlets and novellas, its pages laden with lovely old words like numinosity and serendipity. But the real magic lay in the way the words wove together. There were moments of ravenous joy and molten rage; massive metaphors that snaked out, slippery and sinuous, like great root systems.

So vast was this novel that at times it seemed to contain almost all there was worth knowing in life. And close up it could be hard to appreciate. Some couldn’t see the words for the chapters. But given the perspective of time and distance it revealed itself, coming together, piece by piece – a magnificent jigsaw, resonating in the memory and becoming a small part of the beholder.

For generations people came from all over to view this novel, to refresh and stimulate themselves in its shady pages. And though not all understood, agreed with, or admired its every part, they couldn’t help but marvel at its achievement and wonder at the wisdom and patience of the person who nurtured that first seedling sentence all those years ago.

Of course it went. It took days to get through but they finally cut it down, razed and slashed and burned along with the rest of the forest. Not viable, said the word rationalists, who re-planted the land with language of a more practical nature. If in their richness and diversity the old-growth novels were akin to Oak, Birch, Beech and Cedar all growing together in the one forest, then the new plantations are like Poplars – vast tracts of Poplar novels and nothing but.

It’s argued they’re a hardy species that provide good dollar-value to the acreage. They can be quickly produced, cut down and pulped to make way for the next crop. And true, there are sub-species within the Poplar Novel. Some grow into Thrillers and Romances; there are Gothic revamps, full of rutting vampires; acres of New-Age, Self-Help and great thickets of celebrity biographies. All accessible, yes. But lacking any real sense of transcendence and wonder.

Meanwhile, words deemed rogue or redundant are culled by Linguicide Squads – a brutal breed of bonsai topiarists who savagely prune and hack what grows, to yield stunted little tracts. Conversely, The Department of Communicant Functionaries engineers bewildering briars of Franken-language, with words like Visioning and Incentivate, to mollify the concerns of ‘key stakeholders’.

And Dr Seuss wept.

I know life’s simpler now that we all speak the same language. Still – and I know what I’m about to suggest is highly criminal – why not plant a word in secret. Nurture and admire it, see what grows.

You’re a teenager and your mother is dead. Your father marries a narcissist who hates you for your beauty…

… She sends an assassin to kill you; he can’t see it through and cuts you loose. You run deep into the woods where it is damp and dark, you who have grown up with servants and glowing fireplaces. You meet seven strange little men who want you to be their maid, and you agree, princess though you are, and they let you get on with it without even making a pass at you. Your stepmother comes after you – want something done right – and twice tries to kill you. The little men stop her. You are stuck in the small house where you clean and wait. The third attempt on your life comes and you are poisoned. Your heart freezes. The little men lay you out in a glass coffin and mourn, though you don’t see this. You see nothing but darkness until a prince wakes you with a kiss you didn’t ask for and whisks you away to be his bride. You are still sleepy. At the wedding, your stepmother appears and rants at the guests. Your prince has her captured and forced into a pair of red-hot iron shoes, which make her dance until she dies on her feet. Through this, you stand back and watch and say nothing. You wonder where he got the shoes.

Snow White is a strange story. A German fairy tale published by the Brothers Grimm in 1812, it is full of dark twists and turns, sorcery, loaded symbols. Why, then, do we come back to it over and over and again?

Angelin Preljocaj is speaking to me from Aix-en-Provence, where his world-renowned contemporary ballet company is based. French, but of Albanian origin, Preljocaj is softly-spoken and deferential, apologising repeatedly for his (excellent) English. His radical retelling of Snow White will be performed over one week at the Opera House this June. To him, the story has never been more relevant.

“Actually, I think it’s very modern. With the progress of the medicine, of surgery esthétique, things have changed in the last hundred years. A woman of 50 is now very young and well-preserved. Because of that, we can see this woman walking with a daughter of 18 – and they are both very beautiful, full of beauty.”

Preljocaj is fascinated by the symbolism and psychological complexity of Snow White. Does he think, then, that modern mothers want to kill their daughters?

“There is the desire unconscient – perhaps not physically to kill, but to avoid the daughter because she is like an enemy. These days women all want to be not just a mother, but all other things. Impassioned by work. Still to be in love. When you are a mother, it is not that everything stops. In many ways, this is normal and good, but it can be bad. That’s why I think Snow White is so interesting.”

Photography by Jean-Claude Carbonne

The stepmother is the burning heart of Preljocaj’s Snow White. Fiercely sexual, couture-clad, manipulative. At the same time, she is a tragic figure because what she seeks – youth, beauty, romantic love – must inevitably retreat from her. She is doomed. The final scene sees her forced to dance to her death, in punishment for her cruelty to the innocent stepdaughter. It is brutal. Does she deserve this?

No, says Preljocaj – nothing is so simple. “She is a woman who wants to stay alive: in society, in the world, in love. She is psychologically complex.”

Did he consider, then, softening this sharp edge of the Grimm’s telling? Almost abashed, Preljocaj admits that he could not turn away from the stepmother’s final, frenzied dance. “The brothers created something very seductive for a choreographer when they wrote this ending.”

While Snow White seems less potent in Preljocaj’s imagination, the relationship between the two women is more significant.

“There is the scene with the apple. This is bizarre – it is like an inverse love story. The dynamic between the two women is both tragical and sensual in this moment.” At the end of the scene, there is no compromise; stepmother dominates and forces the apple down Snow White’s throat.

Preljocaj is a collaborative artist by nature, and his ballet is a triumph of shared inspiration. Costumes are designed by Jean Paul Gaultier and are not for the faint-hearted, giving us a Snow White both infantile and alluring, and a stepmother who is pure dominatrix in stilettos and leather. Ten years after they began work together on the project, Preljocaj sounds like he still can’t believe his luck. “Jean Paul was incredible, prolific. We had the first meeting, I explained my idea and he was very excited. After just one week, he sent me 200 drawings. And most of the production was already there in these drawings – we just had to choose.”

Photography by Jean-Claude Carbonne

The production set is designed to shift almost instantly, without breaking the rhythm of the story. It features a mountainside wall from which the miner dwarves emerge from holes, leaping and arcing like enchanted abseilers.

When he speaks of his dancers, Preljocaj’s soft voice softens further. “I’m not looking for a dancer; I’m looking for a person who dances very well. It is very particular. I’m looking for the person first.”

“My idea is that each company is like a bouquet – a flower composition. Sometimes it is just a huge composition of roses. But my company is roses, peonies, even some wild flowers.” It is intensity and precision that characterise these dancers and this, alongside Preljocaj’s intelligent use of abstract movement, lifts the work from pantomime to art.

Preljocaj’s Snow White is not for children. It is a story about grown-ups, for grown-ups, told by performers who speak with their bodies. In its strangeness, the story captures us. In its exploration of the dark traps of desire, it holds a mirror to all our human parts: white as snow, red as blood, black as ebony.

Ballet Preljocaj’s Snow White is at the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House, Wednesday 6 June to Sunday 19 June 2018. Tickets $59 + booking fee.

“I’m 20 years old, I don’t want to fight. I don’t want to walk towards death with my own two feet.”

Ibrahim is one of more than a million Syrians holed up in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley. He is a refugee from a war that has engulfed his homeland since he was 13 years old. Like so many Syrians, he’s enduring a life in limbo, consigned to a tent settlement about 30 minutes from the Syrian border. But home might as well be a world away.

As the Syrian war enters its eighth year, Ibrahim is at his workplace, a building site next to the camp where he lives. It’s a ribcage of what will become a modern apartment building rising from the ground. He’s painting the ground level a mustard yellow.

Over 5 million people have been forced to flee the country. Half of them children. Ibrahim is just one of them in a war so long he has grown up in refugee camps. With so much distress and disruption at home, UNICEF estimates there are 8.4 million Syrian children in need of humanitarian aid – across the country and in places like this.

The refugee camps are safer than being back home, but there are still dangers. “It’s really only Syrian civilians that are dying,” Ibrahim says. “Foreign countries are joining in the fighting. The Syrian people are suffering the most. The children, women and the girls.”

According to Ibrahim, most Syrians in Lebanon would like to move to Europe but the cost of getting there is huge. And then there is a risk of drowning and death.

“I’m working and saving up so I can save rent for a tent,” he says. “The tent owner comes and demands his money. You don’t even get a chance to rest. No day off to relax or to recover. We keep working. Here there’s nothing. It’s just working and sleeping. And sometimes there’s no work. Today we’ve eaten but we can’t be sure we will find food tomorrow.”

A few days earlier, a security briefing takes place in a small basement room of the World Vision office on the outskirts of Beirut. With me are Afghanistan-based photographer Andrew Quilty, a Lebanese filmmaker, and a VICE Australia journalist. A map of Lebanon is tacked to the wall. The security officer is using the aerial on his two-way radio as a pointer, jabbing it at the map to indicate places where we can and can’t go. A mosaic of risk, unrest and tension.

Lebanon is bordered by the Mediterranean to the west and Israel to the south. To the north and east is Syria. We are heading to the Beqaa Valley, which runs the length of the eastern border, and which over one million Syrian refugees now call home.

On the drive to Beqaa, tourist signs for vineyards — and even a chateau — mingle with road signs for Syria and military checkpoints. The region once known for its tourism is now a synonym for war.

The first refugee camp we visit is in the Beqaa Valley, and from the moment we arrive at the camp I gain a mate. His name is Khaled, a 15-year-old Syrian from Daraa. A refugee from the town where the war began.

In March 2011, as the ‘Arab Spring’ toppled leaders in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen, 15 youths from Khaled’s home town were arrested for allegedly spraying graffiti critical of the Assad government on a high school wall. When the arrests sparked demonstrations, Government troops shot dead three of the protestors; a fracas now considered the point at which the civil war erupted in Syria.

At the camp, Quilty is taking photos of teenage refugees outside their tents, focusing on children who have turned 18 in the refugee camp. Many of them have spent their entire childhood in the Beqaa Valley.

There is a faint buzzing in the sky, and a white glint of sunlight from a drone high above. The drone, the size of a small plane, circles before steering east down the Syrian border; war follows refugees wherever they go.

On our second day in Beqaa we return to the camp. We’ve lost our translator to illness; my Arabic is worse than Khaled’s English and we have exhausted our few words of mutual French. So, soccer it is, and after one kick we’re joined by a throng of eager children.

After the game, Khaled re-adjusts a Band-Aid on his foot. It’s covering a nasty cut which on closer inspection is deep, swollen, and badly infected. I fish out a basic first aid kit from my bag and clean and dress the wound. He clearly needs stitches. Only later do I learn that a glass plate had fallen on his foot. I hand Khaled the kit and urge him to clean the wound each day.

He’s just one in a camp of hundreds of people, amongst thousands of camps.

Photography by Andrew Quilty

In April, living rooms around the world were again flooded with images of children and adults gasping for breath after being exposed to deadly nerve agents. The total number of gas attacks in Syria is unclear – the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic puts the number at 34, while the American ambassador to the U.N. accused the Syrian government of “at least 50” attacks. Human Rights Watch has reported 85.

Only weeks after the latest gas attack, the Syrian government introduced Law Number 10, a property law which requires citizens to prove ownership of their homes in person in a matter of weeks – else their homes and land will be sold off to property developers at auction. Under this new law the displacement of millions of Syrians could become permanent.

Yet amidst this crisis, developed countries like Australia continue to reduce aid budgets: $11 billion has been cut from the aid budget in the last five years. The unpredictability of funding throws up challenges for the humanitarian workers and the refugees escaping the conflict. Declining aid budgets put more pressure on bordering ‘host’ countries which can then act as a push factor for refugees to travel further afield, further compounding the tragedy of displacement.

There’s no way to know when or if the social fabric of Syria will be rewoven. Wynn Flaten, Director of World Vision’s Global Syrian Crisis Response, says the devastation of Syria’s displacement will be generational.

“When you look at children in the right environment, they have hope, they have dreams,” he says. “Even in the worst circumstances one wants to be a doctor, another one wants to be a teacher, another one wants to be an engineer.”

“Yet when you look at youth, who have lost out on education, they have lost out on the opportunity to learn practical skills, and they say, ‘what kind of job can I do?’”

Photography by Andrew Quilty

Evana is Khaled’s mum. Back in Syria Evana was a farmworker, the family’s breadwinner. Her brother, Khaled’s uncle, was slaughtered in the war. The family had to flee their farm on the outskirts of Daraa in fear that they would be next.

Since then, their home in the Beqaa Valley has been a tent made of canvas and an old billboard held up by a frame of recycled wood; their hallway floor black plastic, muddy with footprints. “If we go back to Syria my son will have to join the army. People are being forced into the army. It scares me,” Evana says.

The tent has two rooms — the main room at the front and a smaller one out the back. A woven rug and pillows fill the larger room. It’s both lounge room and sleeping quarters.

“We went over the mountains to get to Lebanon,” Evana tells me. It was a difficult and dangerous journey. They dodged soldiers, snipers and indiscriminate bombings. A mistaken identity can be deadly. “It was hard for us, it was risky, because we didn’t have papers. We went into the mountains at night, which made climbing them difficult.”

It’s not just bullets and bombs that Evana and her family fear. It’s hard to count the ways war has of inflicting cruelty on women and children.

“We had the chance to travel outside of Lebanon, but my husband would not allow me to travel, so we stayed here.” They are now separated, but he recently paid a man to try to steal Khaled away from the camp. Evana’s neighbours heard her screams.

“The men gathered around and stood with me. They stood by my side. He is too scared to come back here again.”

Khaled and Evana. Photography by Andrew Quilty

According to Wynn Flaten, the biggest challenge facing aid workers in a generation is the constant shrinking of the humanitarian space where agencies like World Vision can safely deliver assistance to those suffering or displaced by a crisis.

“Humanitarian workers no longer have access to all areas where a crisis is occurring,” Flaten tells me.

Historically, humanitarian workers were shielded in a conflict. Principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence were largely revered. This is no longer the case. In a cynical world with cynical wars, they are now as much a target as anyone.

In January 2018, gunmen stormed the Save the Children office in Kabul, killing five and injuring many more. In March 2018, the International Committee of the Red Cross aid convoy was forced to turn around on the way to East Ghouta after a ceasefire was breached by heavy shelling.

“Places of refuge which you would think would be immune from attack, like medical facilities, or schools or humanitarian convoys, those are also targeted,” Flaten says. “For humanitarian access and the humanitarian workers, it has become much more dangerous and problematic.”

On our last day in Beqaa, Ibrahim is at the building site. He seems like he will earn enough for his tent. Cap on backwards and covered in paint, he smiles and thanks us. But how much longer can he last here? He’d already said, “If the war doesn’t end in Syria, we can’t go back. I’d be facing conscription [now I’m of age].”

I visit Evana to enquire about the infected wound on Khaled’s foot. “Back in Syria, healthcare was free, here we are suffering with nothing,” she says.

When he’s well, Khaled works in a garden for a local property owner. He is paid about AUD$3.00 a day. “I won’t allow him to go to work until it gets better,” she tells me.

Evana can’t afford to take Khaled to hospital — so she applies ointment and dresses the wound herself. “In Lebanon, everything is expensive. I work really hard in case someone gets sick or needs medicine, but we have to pay rent for the tent.”

Photography by Andrew Quilty

Back in Beirut, we try to get a doctor to visit the camp but we’re told none are available. It’s hard to know how we can help Khaled get treatment. World Vision’s role is to provide clean water, hygiene and sanitation, early childhood education, child protection, and livelihoods. Other non-governmental organisations are responsible for healthcare, and each organisation sticks to its role in the camps. The boundaries must be clear and respected so that we can all work together effectively. There are a million people with a million issues. A Lebanese filmmaker, Mark Karam, who is making a documentary, offers to help me coordinate a doctor’s visit for him once I return to Australia.

Flaten says sometimes he feels like the work he’s doing at World Vision is adding drops to a bucket of water. In the scheme of the human misery he confronts, it isn’t much. But it’s something.

Years ago, he realised that if anybody wanted to make a living trying to alleviate the misery of others, they’d need to be fully committed to what they did. “This isn’t just a job, there is an ethical and a moral imperative to do as well as we can and never be satisfied with what we are doing.

“No matter the level of effort, it just never seems enough. At least we try. I think the biggest failure would be to not try at all. So, we do our best, and then we try to do better.”

Photography by Andrew Quilty

Angus Smith is a freelance journalist and Public Affairs Officer at World Vision Australia. He encourages you to donate to the Syria crisis here.

Ibrahim’s full interview is captured in a mini-documentary produced by VICE, World Vision Australia and World Vision Lebanon.

About 40 people are scattered around the Hawkesbury Helping Hands van, sitting at picnic tables waiting for food to be served. Most are men, just a few women. All are gaunt and middle-aged or older, dressed in an assortment of op-shop discards. It’s unseasonably hot for this time of year, but thunder is threatening to the west. Tough weather to live in without benefit of air con or a roof. Soon enough, winter will create a whole new set of challenges.

Linda Strickland has about five conversations on the go as she bustles about. Hawkesbury Helping Hands is the service she set up to deal with a rising tide of homelessness in the Windsor and the Hawkesbury region. She seems to know everyone here by name and receives two marriage proposals tonight, once the burgers and salad are served.

The Hawkesbury and Nepean Rivers virtually encircle Sydney. City-dwellers associating homelessness with CBD street sleepers might only know these rivers from weekend house-boating or fishing trips. But anecdotally there are thousands of homeless people living in secluded enclaves from Windsor through Ebenezer and on to Wisemans Ferry, down south to Penrith.

“It’s impossible to figure out how many people are sleeping rough, d’yaknowotimean?” Linda says. “You can never get the true count because the Hawkesbury is so big and there’s so many places where they’re hidden away.”

She points out subtle distinctions amongst the diners: “Rough sleepers over there, car dwellers over here. On that other bench, by the river bank, that’s our long term campers. On a weekend that’d be full of kids. A car is one step up from a rough sleeper, although a lot of the people living in cars would say it was bad… Depending on the weather, it’s brutal.

“Those people there with the shopping trolley full of stuff are newcomers,” Linda says. The newcomers – a ravaged, skinny blonde woman, a short, confused-looking man with a withered arm, and another older man – sit apart from everyone, smoking.

“We set them up last night with a tent and they slept in the park.”

I sit down with two other men as they finish eating. Dave’s about 40, but he seems weary, older. Kimbo looks ancient, with a pale bushranger’s beard discoloured by tobacco and the elements. Dave starts talking to me about his hidden campsite by the river when Kimbo hands me a small note pad. On it he’s written:

LIVED ON THE RIVER FOR 18 YEARS.

WE WAS KNOWN AS THE SUNSHINE CLUB.

That’s when I notice the hole in Kimbo’s throat and realise he can’t talk.

We’re interrupted by another river-dweller, Wendy, an anxious, barefoot woman eager to help. She asks Dave, “Can we have a chat about these new people? We’re thinking about putting them in Steve’s old camp.” Dave nods thoughtfully.

Kimbo passes me another note.

WE DOIN A FUNDRAISER BBQ FOR LINDA NEXT WEEK.

That’s an interesting wrinkle. The homeless helping their helper.

I’m hoping for more information but Kimbo vanishes – and Dave and Wendy are engaged in the more pressing business of getting the newcomers a campsite.

Linda bustles over to me. “Those three new people, they’re not in a very good way. I’ve asked Dave and Kimbo to look for a good camping spot but first we’ve got to transport their gear.”

Dumped and burnt, Hawkesbury River 2018. Photography by Dean Sewell.

Linda started her vocation seven years ago. She had a shop in Windsor selling the hundred pairs of cowboy boots she’d collected while living in Texas.

“One night the dogs went crazy and we looked out the window. There was a guy going through our garbage bin. I went outside and asked him ‘do you want a sandwich?’ but he ran away. That was my first in-your-face experience of homelessness, because they’re mostly hidden around here.”

Linda and her daughter began volunteering at a local soup kitchen. “It was closed on weekends so we said to everybody, ‘Meet us in the park on Saturday.’ The first Saturday we had seven people, now we have up to 80, sometimes 100.”

Mother and daughter had been at it for four months before a local journalist asked what they were called. Linda improvised the name – Hawkesbury Helping Hands. It stuck. “We had no idea in those days – we’re a tiny grassroots organisation but our community is huge, the largest area of Sydney.”

Their first year was tough. They were feeding people with their own money and donations from the local community.

“From mid-December to mid-January, nearly every service shuts down on the Hawkesbury but us, so we’re up to 10-15 hampers a day and amongst all that we do a free Christmas Day lunch. So till mid-January it’s a lot of work and little sleep. We run a breakfast club for kids and take lunches to the local high school five days a week.”

Over the past two years, Linda’s noticed a steep increase in people coming to meal services. “A lot of people can’t afford to have electricity on. How are they supposed to cook or have a shower? The rents are absolute murder. A one bedroom flat is $250 a week. If you’re a single mum it doesn’t matter how many kids you’ve got, you’re still gonna find it tough.”

As the lunchers start to disperse, Linda begins packing her van, still talking to people, asking pointed questions about living conditions, handing out brochures for specialist services.

“I would say 25 per cent of the people that come here are the working poor,” she tells me. “Living paycheck-to-paycheck. Once they’ve paid rent and bills, they’ve got nothing. We have a lot of single mothers. People think they’re all uneducated. But I’ve had women solicitors living in their cars coming to meal services, single women sleeping in cars in my backyard.

“Food is our priority. We’re not funded so we can’t do accommodation, but one thing we can do is make sure they have food, toilets and a safe place to be and if they have nothing we can give them a tent or a swag.”

Photographer Dean Sewell has been co-opted to drive the three new arrivals across the river to the unofficial camping grounds. Linda offers me a lift to meet them.

Her van is overflowing with boxes of food. I’m balancing trays of pavlova on my knee as we pull up in a car park alongside the wide, brown river.

“There’s been people living on the river bank here forever,” says Linda. “Aboriginal people, convicts. There’s caves up in the mountains where I’ve heard people have been camping for years.”

Linda takes off, late for a meeting.

It’s sweltering as I walk across the grassy river flats. Orchards are shimmering to the west, storm clouds leaning testily on the mountains. I can see Dean’s ute, people gathered round another vehicle. Beyond them a jungle of weeds, willows and wattle.

Kimbo’s brought a ride-on mower, on a trailer hauled by his battered Statesman sedan. Dave’s underneath the mower, trying to release the drive belt to start the machine. Finally he climbs out, shaking his head.

“The whole frame’s cracked,” Dave says.

Kimbo’s leaning on the trailer. A hoarse rattle issues from his throat. I see him wiping blood from the hole.

The three newcomers are standing by Dean’s car, looking warily at the thick bushland. Later it’s explained to me that DK has a form of cerebral palsy, a withered arm and a speech impediment. The older man is deaf. Preteena smokes cigarettes intently, as if she’s fighting rising panic. They all look as if they’ve endured some unspeakable trauma.

Dave and Kimbo show them one potential campsite, but DK looks unconvinced. The grass is very thick and there’s debris left by a previous camper – old tents and household rubbish. It’s a snake’s paradise.

Preteena and Dave bathe in the Hawkesbury River. Photography by Dean Sewell.

A burly bloke with few teeth and a loud voice strolls up. He’s carrying a golf buggy. He lives further along the river in an enclave of campers that’s been described as ‘rough’.

I ask if anyone swims in the river on hot days. The burly bloke chuckles through a mouth devoid of teeth.

“Some people do. I wouldn’t swim in it myself. All that crap coming off the turf farms and orange orchards and everywhere else.”

He points back towards some thick scrub. “Somewhere over there would be good for a camp,” he says, pointing into the thick scrub where we came from. “You don’t want to bring ‘em any further up here. Steve might get a bit funny if they get too close to his camp and he has a few beers.”

Meanwhile, Wendy arrives, barefoot again, and invites everyone to her place for a drink of cordial, but nobody responds. Her husband Robert suffers from dementia. Robert is able to drive their car but can’t engage in conversation. The couple sleep in the car with their small one-eyed dog, Winky.

Dean and I end up visiting Wendy and Robert’s nearby camp. It’s a sprawling mess, dominated by an old caravan. Stacks of hoarded materials, many shrouded in tarpaulins. Sagging tents are full with Wendy’s damaged and weather-worn goods.

Living without toilets or showers in those strangely crowded conditions cannot be pleasant. But Wendy puts a brave face on it. She fishes out tarps, ropes, cups and plates and says she’ll take them over to the newcomers.

Robert, Wendy and Winky at their camp. Photography by Dean Sewell.

Dave selects a site deep inside the forest. It’s all burrs, wasps, flies and heat, abated somewhat by the sweet smell of fennel, which grows in abundance. Kimbo is despatched into town to fetch a new mower.

A qualified chef, a landscaper and welder, Dave describes himself as “an outdoors person”, which is handy as he lives on the river-bank with a cockatiel parrot.

“I’m from New Zealand, but I’d been living here for 16 years when I had my divorce,” he says. “When we split up she got everything, I got the bills. I had nowhere to go, so I came up and got a job concreting in Windsor. I saved up ten grand and bought a boat in Rose Bay. I was living in it till it sunk on Australia Day, so the second time round I came back here and got some welding work for a while.

“I was doing ok, paying child support for two kids, then the work closed down. I was due to get a tax return of five grand, then there was a child support over-assessment, so now I owe them eight grand. I’m only getting $375 a fortnight and I owe $20,000 from my marriage. I gave up my dodgy caravan, I was paying $220 a week for that. I lost my passport and had my wallet stolen, so now I’ve got no ID. Then every day was a nightmare looking for somewhere to live. In the end I just gave up and slept in the park.

“Being on benefits is not the bludge it’s made out to be. If you miss a job provider appointment you get suspended. If you don’t have money for an Opal card how do you get there? It’s catch 22. You’ve gotta jump through hoops just to get paid, it’s kind of a job on its own.

“I used to see homeless people and think well, get a job, now I see it’s not that easy.”

Dave doesn’t smile much, but he says living on the river isn’t too bad.

“Everything’s close by. It’s a lot quieter than the city, cheaper living, but it’s hard to find a job. It does get cold in the winter, but you’ve got the library to sit in. There are people living in abandoned places, those that are on the streets never sleep.”

When Kimbo returns with a functional mower, they start carving a pathway into the long grass. It’s hot work. Dave’s pushing the machine while Kimbo peers over the steering wheel, dodging tree stumps and old tyres.

Finally they iron out a flat spot with some shade. They’re followed tentatively by DK, Preteena and the older fellow – I never discovered his name – clutching their bags and the tents that Linda gave them from Hawkesbury Helping Hands.

“The snakes aren’t so bad,” says Dave. “I see one every now and then but I don’t mind ‘em. As long as they don’t get my bird.”

Thunder is rattling and a cool wind washes in through the trees. It commences to rain.

Kimbo on his lawnmower. Photography by Dean Sewell.

A week later, at the fundraising BBQ in Richmond’s industrial suburb, Dave, Kimbo and Preteena are sitting in a large jury-rigged marquee in the stifling heat, waiting for customers. Preteena looks more relaxed, but her thin, pinched face speaks of more than one improvised exodus from hard times.

This lot, full of old machinery and a shipping container is the headquarters of Kimbo’s lawn-mowing business. It’s across the road from a dance academy where young girls in tutus are giggling. The RAAF base is up the road and Caribous occasionally roar overhead.

Kimbo’s proudly showing off his mowers in various states of repair. He reckons he has seven ride-ons and 30-40 push mowers. Dean and I buy rissoles on a roll for $3.50, cans of cold drink for $2. Dave starts cooking on one of three large commercial BBQs.

Kimbo passes me another of his notes:

I HELD A SHIT CART EVENT TO RAISE MONEYS.

TROTTING SPIDER WITH W/C CAN ERECTED ON IT. STIPULATION 2 HAD PUSH 2 PULL

He’s got several notepads bought in bulk. He claims to have started a radio station in Windsor, presumably before he had throat cancer. It’s not clear where Kimbo lives, but he reckons he’s got plenty of mowing work.

After we’ve eaten a silence descends on the BBQ. Dave’s scraping fat off the hot plate. He shows phone pictures of his campsite and the tiki bar effect he’s created, complete with flower arrangements and posters.

“I wanna build a little cordwood house just on the turf,” he muses. “No foundations in the ground. Council wouldn’t like that. I’d like to open my own business, but I’ve got so much debt from my marriage I can’t get a loan. What do you do?

“Homelessness is not about sitting around all day drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes. It’s stressful and it’s hard to get out of. It’s a vicious circle. You think you’re getting ahead and something happens and you fall back again, and you say to yourself, why bother? Why do I try?”

No customers show up to the barbeque.

When photographer Dean and I return a few weeks later things have changed dramatically. No-one’s home but the newcomer’s camp is well established with tents and tarps, a leveled floor, gardens and trenches to mitigate the recent heavy rains. The kitchen has a table, benches and shelves made from pallets. Cacti and basil planted in the garden.

There’s even a rickety gate. I recognise Dave’s handiwork. Having moved in to this camp, he and Preteena are in a relationship.

There’s a well-worn track to Wendy’s camp. Her hoardings have grown. Two more gazebos are pitched out the front of the old caravan, amid growing piles of damp paraphernalia. She’s been texting Dean with increasing desperation, asking him to come and help her out as she’s become isolated from the group. She blames Preteena.

As we’re waiting in the hot sun their car pulls up. Wendy emerges in a faded dress. “Oh thank goodness you’ve come. I’m just exhausted. I desperately need help.”

She’s looks tired, close to tears. There are scratches on her arms and legs. She’s clutching Winky like a life preserver. We say hello to Robert and he looks like he’s going to say something, but nothing comes out.

The recent heavy rains have exploded the undergrowth. Weeds and acacias hide jeering choruses of crickets, cicadas and frogs. Most of Wendy’s hoardings are covered in tarps, like a Christo exhibit.

“I know it must look scary from the outside,” she says. “But it’s all stuff I want to have in my house. I still envisage having a life one day.”

Wendy says she owns a house in town but had to leave it because Robert, increasingly ragged with dementia, kept locking them out. They have a daughter with autism who seems to have made a life elsewhere. She wants to sell the house, but it too is overflowing with compulsively acquired material. As are her three industrial containers on the edge of the common, visible from this campsite.

Wendy asks us to help her empty water out of roof bulges in one of the gazebos, propped above what seems to be the A grade rubbish. She demonstrates how to adjust the plastic jerrycans of water the guy ropes are tied to, in order to tension them. Then we’re shifting boxes of things around on a makeshift platform of pallets. Toys, chairs, prams, mouldy books, boxes full of empty boxes. Fishing rods, mattresses, rusted tins of food, a complete aluminum camping set of pots and pans.

She knows the provenance of every item. Her rambling commentary finds a laser focus if anything catches our attention. “That’s a vintage motorised fridge. The motor’s missing and of course it would need power.” She points out some rolls of dirty material in between tumbledown pallets. “That’s top quality commercial vinyl and carpet tiles I’m going to put on the pallets. I want to make a nice space for Robert to sit in out of the sun.”

Anything we do is purely cosmetic and makes no difference to the overwhelming mountains of junk, but our labours seem to make Wendy happy.

Robert watches silently, scratching his head.

Winky is scrabbling through the weeds. A rustle in the long grass announces what could be a snake. I wonder how long this little one-eyed dog will survive this jungle.

The newcomer camp. Dave considers home improvements. Photography by Dean Sewell.

We tell Wendy we’ll come back in the morning to put up a new gazebo and walk back through the bush to the other camp. Dave’s sitting on a couch smoking. His bird is sitting too quietly in its cage.

“There’s something wrong with her [the parrot],” he says. “She’s usually singing and dancing about.”

Preteena phones him. She and DK are on the train to Windsor from Blacktown. Dean agrees to go pick them up. Dave talks about one of his business ventures. He used to weld sculptures out of steel tubing and sell them till his ex-wife threw them, and him, out.

He talks about ‘booting’, a computing term for kicking someone out of a chat room. I find it difficult to equate Dave’s CV as a welder and concreter with a secret life as a hacker, but he seems to be describing coding protocols that require a lot of expert knowledge.

“I used to build websites. If someone didn’t pay in the time agreed I had my own back door code to get in and disable the website. Only had to use it twice.”

He’s enthusiastic about pooling his money with Preteena and DK to rent a house. “Then I can get a job and get my shit together.”

Later, Dean, Preteena and DK arrive back loaded down with groceries. They’ve got lots of food from various charities and a stack of plastic cups from a Scientologist’s stall near Blacktown station. Preteena greets me warmly, like I’m an old friend.

DK gives a guarded look and ignores me.

One of DK’s occupations is begging in town. It’s a practice known as ‘coal-picking’. He’s been involved (unromantically) with Preteena a long time. From what I can gather he took the responsibility for some crime they’d both been involved in and he did jail time.

Seeing Preteena take up with Dave had prompted a competitive spirit in DK and he’d asked her to marry him. She rejected him.

Preteena tells me she’s suffering from both schizophrenia and cancer. She’s certainly had a hard life. She was kicked out of home by an abusive father in a small Queensland country town at age 14. She’s been raped several times and suffered other unspecified abuses.

But Preteena’s tough, a survivor. She’s raised six children and is very proud that the father of some of them is an Aboriginal man. She takes a kind of fierce, malignant joy out of living against the grain of a judgemental system.

“I’m a chef like Dave. He’s not the only one who can cook,” she claims, in a bellicose squawk. Turns out she’s been a shearer’s cook, working big sheds in Queensland. But she’s not cooking tonight. Tonight she wants to party.

She sits at the other end of the couch from Dave. They’re both drinking cask wine out of sports drink bottles. He keeps bringing the talk around to houses he’s seen in the paper, real estate agents he’s talked to. Preteena isn’t interested.

Everything’s too expensive.

Preteena. Photography by Dean Sewell.

She’d rather talk about who she’s seen in town. Her stepson, “a real bad-boy”, made an appearance briefly, before being recognised by the police and scarpering. Somehow she’d spent $700 today. The blame for this is increasingly, it seems, being laid at DK’s feet, though Dave, inadvertently, is responsible too.

“You cunts owe me money!” she growls. “Yers have both been sayin’ ‘lend me money, I’ll pay ya back’.”

“I get paid tomorrow Preteena. Give us another cone,” DK demands.

“You fucken better. I’ve only got twenty dollars left out of seven hundred.”

Wendy can be heard, howling and sobbing in her camp. To drown out the noise DK has a radio tuned, loudly, to a local radio station playing ’80s hits. It inspires Preteena to reminisce on a recent triumph.

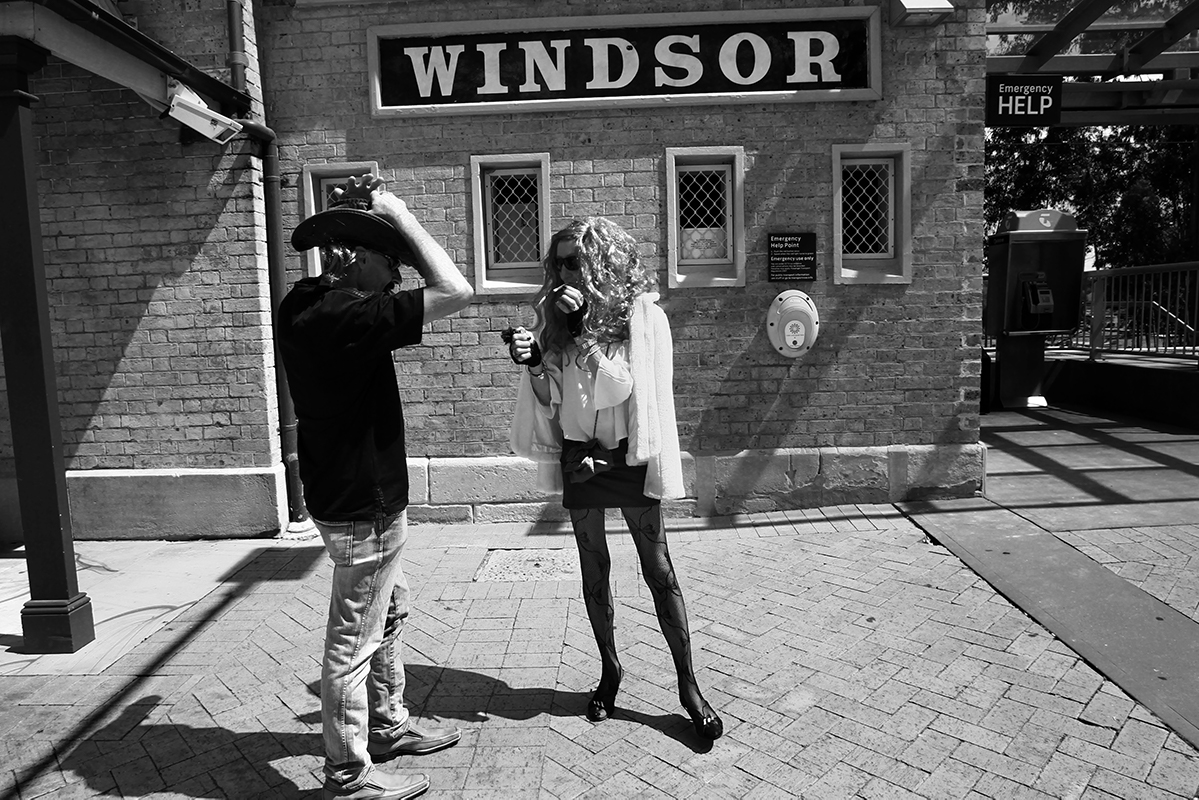

“Did you see the photos Dean took of me before the Mardi Gras? Gawd, I’ve never had my photos taken like that before. He got me to face this way and turn that way, get the best light an’ that. I was all dressed up in me stockings and mini skirt.”

They’d taken the train to Strathfield, but that’s as far as they got. Dave bought a bottle of whisky and Preteena had her own Mardi Gras, commuters gawking as she prowled the platform, giving a raunchy exhibition in her sheer stockings, g-string and short skirt.

“I wasn’t afraid. I had my boys with me.”

During the night the camp has two other visitors, both men in their 60s. They work and sleep rough further along the river. Both comment on the noise coming from Wendy’s camp. Preteena’s personality changes remarkably, becoming effusive. She makes them cups of coffee and butters bread for a snack. It’d be easy to believe she was a stabilising influence in this camp, but for the relapse into character the minute they’re gone.

We can still hear Wendy caterwauling. Occasionally Preteena hollers “shutup ya mad bitch!” As it’s getting dark Wendy comes down the path, arm-in-arm with the tottering Robert. Preteena goes to her in a show of solidarity. Wendy recoils. She demands to know why she’s being reviled and ignored. DK is at the gate telling Wendy to go.

Eventually Wendy alludes to Preteena’s ailments. “She hasn’t got cancer,” she says. “She’s just smokes too much pot.”

Dave loses his temper at that.

“Fuck off!” he bellows.

Wendy retreats howling, dragging Robert with her.

Dave and Preteena at Windsor Station on Mardi Gras day, 2018. Photography by Dean Sewell.

With the night seeming to slow down, Dean and I stretch out on swags. But we can hear Preteena getting drunker and more argumentative. “I want my fucken money. You cunts owe me 700 dollars!”

DK goes to his tent, still playing the radio; ‘Africa’ by Toto to drown out Preteena’s profane croaking. Dave has words with him and Preteena starts screaming. Wendy, too has started howling again in the distance. This sets the tone for the next several hours.

Eventually Preteena concludes that DK stole the money.

“I’m callin’ the cops!” she screams.

Soon the policeman on the other end of her phone call is trying to get a fix on her position, but her explanation is crazed, incomprehensible. She hangs up.

“See? You better run DK, or you’re goin’ back to jail.”

“That’s it, I’m goin’ to my mum’s,” shouts DK.

He makes it to the gate, the first of many times. But DK is psychologically tethered by a trauma bond so elastic that he constantly ricochets back to the camp, for more rounds of incoherent recriminations.

The night dissolves into an endless cycle of bickering. About 3am I crawl off into Dean’s truck. At dawn he wakes me and we walk about 500 metres to the river.

“The other morning I got talking to a woman exercising her horse,” says Dean. “I told her what I was doing and she had no idea homeless people were even camped here.”

Back in the scrub at the other camp, Wendy and Robert are up. They have no working stove to make a cup of tea. Wendy has barely slept and is incoherent, her long rambling stories going nowhere.

Dean starts moving boxes off a platform in a vague effort to help out. I pull a tarp from a basket to reveal a sodden mess of old clothes.

“That’s washing,” Wendy exclaims. “I haven’t got to that yet.”

“Every day is exhausting looking after Robert,” she confides. “He’s very difficult because he has these inertia traits, so everything you try to do he refuses to help and he’ll be wandering around behind me telling me that I can’t do it either.”

We can still hear screaming and shouting coming from Preteena’s camp.

“It never stops,” Wendy sobs, collapsing hysterically in the long grass. Roberts stands expressionless above her, staring into the white noise of crickets and cicadas. Pulling herself together, Wendy hands us a box of parts to erect another gazebo. When we come to the last pole in the roofing section, it’s not there.

“Where did you buy this Wendy?” asks Dean.

“I got it secondhand from Gumtree. All the pieces are there.”

She sorts through them carefully. Finally she’s forced to admit that the gazebo can’t be built, till she’s found the missing piece.

That’s it. We have to go. As we’re leaving Wendy leans into the car, crying.

“I don’t know what to do,” she cries. “Those people are crazy. I’m afraid. Robert can’t do anything to protect me. He used to be a rehab counselor. He was very good at his job, very empathic. Now he can’t even give me a hug with any oomph in it.

“I was a trauma counsellor too. Our plan was to run our own counseling service from here. Robert used to have a poem above his desk, by a Christian missionary called CT Studd.”

She recites from it from memory:

“Some want to live within the sound

Of church or chapel bell;

I want to run a rescue shop,

Within a yard of hell.”

We leave Wendy tearfully waving goodbye from her fortress of junk. We can still hear Dave, Preetena and DK from the other camp, screaming at each other. Only Dave’s bird has been silent, all night long.

Welcome to the Sunshine Club.

A tent is a home. Photography by Dean Sewell.

ABS stats released in March this year show a 37 per cent increase in homelessness in NSW in the five years leading up to 2018. As homeless people are by definition unlikely to have received a census form, the figure of 57 homeless people given for Windsor seems hopeful at best.

In the camps around the Hawkesbury that photographer Dean Sewell and I visited we met many vulnerable, damaged people, going under from mental illness and society’s inexorably high cost of living. They’re not starving, but they’re bereft of the security and hope most people of this privileged nation take for granted. There are more of them every day.

The first appropriate weekday in May is traditional for British elections, and a whole swathe of local councils were up for election this week, including London’s.

It was the first remotely bearable day after the last flick of winter’s tail – temperatures the previous weekend had dropped to eight degrees. Preposterous! Not that the warmer weather brought out the brave and democratic citizenry; because it remains an axiom of politics that applies across all time, space and cultural difference: follow the money if you want to understand where the power lies. And in Britain, local services are managed by local councils – but they have scarcely any tax-raising powers, while the vast bulk of their financing comes courtesy of the world’s most tedious and self-involved metonym: Whitehall.

You might’ve imagined that those of the Brexit persuasion would’ve been engaging these past two years in a vigorous campaign to reinvigorate local democracy, starting with a major increase in local taxation, but if so, you’d’ve thought wrong. No, local democracy remains an oxymoron in London – one comparable to ‘light well’ or ‘military intelligence’.

The evidence of this was to be seen at my local polling station in the Lansdowne Community Centre, where, when I arrived to vote, there wasn’t a soul to be seen apart from a couple of returning officers, while a few psychic tumbleweeds rolled around on the scuffed linoleum floor.

The ballot paper was a long strip of irrelevance: honest burghers for the most part trying to mitigate the harsh reality of inner-city London, which is that civic space is carved up and meted out according to the dictates of capital returns on the global market, rather than the needs of local people. The polling station is in the very shadow of the new tall building cluster at Vauxhall Cross, and a mere mile as the developer drives from Whitehall itself. Yet there I was idly considering whether there was any point in putting a cross next to the names of the Trade Union and Socialist Coalition, whose electoral slogan – quixotically – was ‘Against All the Cuts’.

Democratic duty done I cycled lazily up to Kwality Café on Brixton Hill for a cup of tea with my mate, Munez-the-Algerian. Munez divides his time between the café, the pub on the corner, and the betting shop a few doors down. Over the years I’ve come to the conclusion he isn’t that observant a Muslim. Munez hadn’t bothered to vote – and neither had his mates Amir and Aziz, who sat in the café chortling and flicking their worry beads. Why? Because they aren’t eligible to, not being British citizens.

The three of them were having a good old cackle about this – because while they hold Algerian passports, they’ve been stamped with the bluish but potent charm: INDEFINITE LEAVE TO REMAIN. Or, as Munez put it: “The Queen has signed my passport, now I can travel anywhere I want, come back whenever I want – rent a flat, get a job, whatever…”

Of course, Munez hasn’t taken a British citizenship test – but he’d certainly pass with flying colours, given his mastery of one of the British’s most compelling characteristics: their schadenfreude. The last month has seen political uproar, and finally the decollation of the Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, over so the so-called ‘Windrush Affair’, whereby it’s emerged that African-Caribbean Britons, who came here in the 1950s and 60s as children but never had their status regularised, have been persecuted by the Government, and in some cases even deported, because they couldn’t prove their citizenship.

The pain of these black Britons is keenly felt in this neck of the woods – given many of them came and settled in south London, and worked at the bus garage which hums 24/7 across the road from my own flat. Much has been made of Rudd’s replacement by Sajid Javid, the first BAME politician to hold this senior government position – especially since he himself is the son of a bus driver, but frankly this is just public relations, not politics – let alone real democracy.

No, if we want the right resources allocated locally we have to make sure national politicians truly understand local issues. Perhaps all former cabinet ministers should have to do penance by working as local councilors for a few years, before they can worm their way back into Westminster. I like the idea of Amber Rudd hanging out with Munez-the-Algerian – it’d give him another opportunity to exercise his very British capacity for schadenfreude.