Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne is not signposted from the street. I catch a lift to the fourth floor where I walk straight in to Bill Henson’s new exhibition, his familiar images hanging on the walls. Like Henson’s previous work at the National Gallery of Victoria, the exhibition is hard to find. I wonder whether this is a conscious decision on the part of the galleries: to protect the artist from scandal or in case of police raid; or to retain the climate of being edgy, the viewer entering a hidden world.

I’m the only person in the gallery, except for a couple walking around with a guide. After a while, they become centre-stage, as I realise they aren’t just looking, they are choosing. One to buy. The guide gives her spiel and as the couple moves, chatting as if deciding what to order on a lunch menu, I get a fierce sense of longing, not for the images themselves, but for this art world that I will never be a part of. I look up the price: $65,000. I imagine the wall for it.

Henson talks a great deal about the reflective space and how he likes to suggest a mood in the gallery by turning the lights down low, creating a dark, lush landscape of stillness and silence. But as I look, the man who is buying does his business wheeling-dealing on the phone in front of me, his loud voice — managing Chinese business relations — filling the centre of the gallery while he paces, his leather shoes squeaking on the floor. The voice of the guide ramps up to do the hard sell to the woman waiting. The guide tells the woman how to feel about the images. Beautiful. Emotional. Vulnerable.

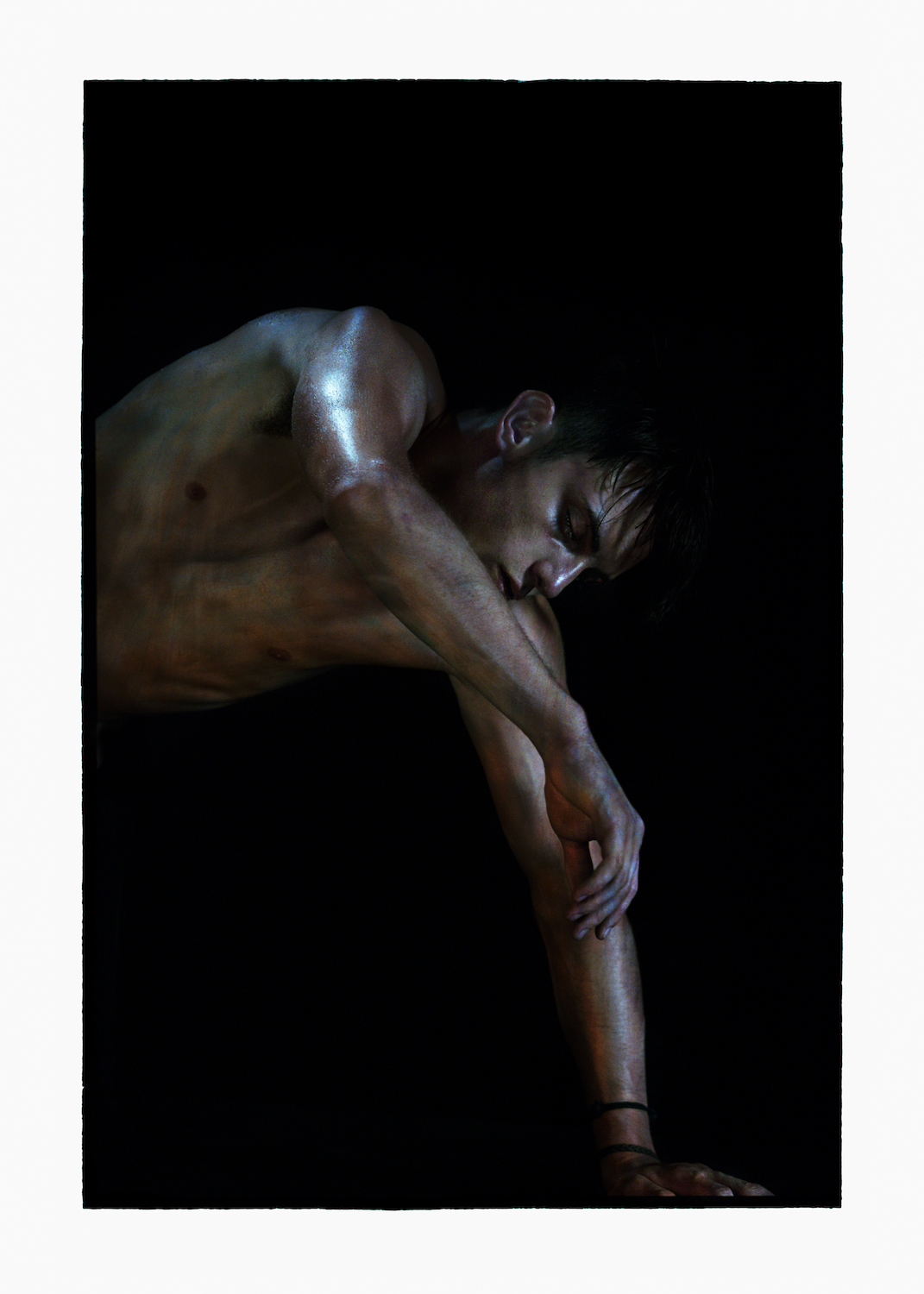

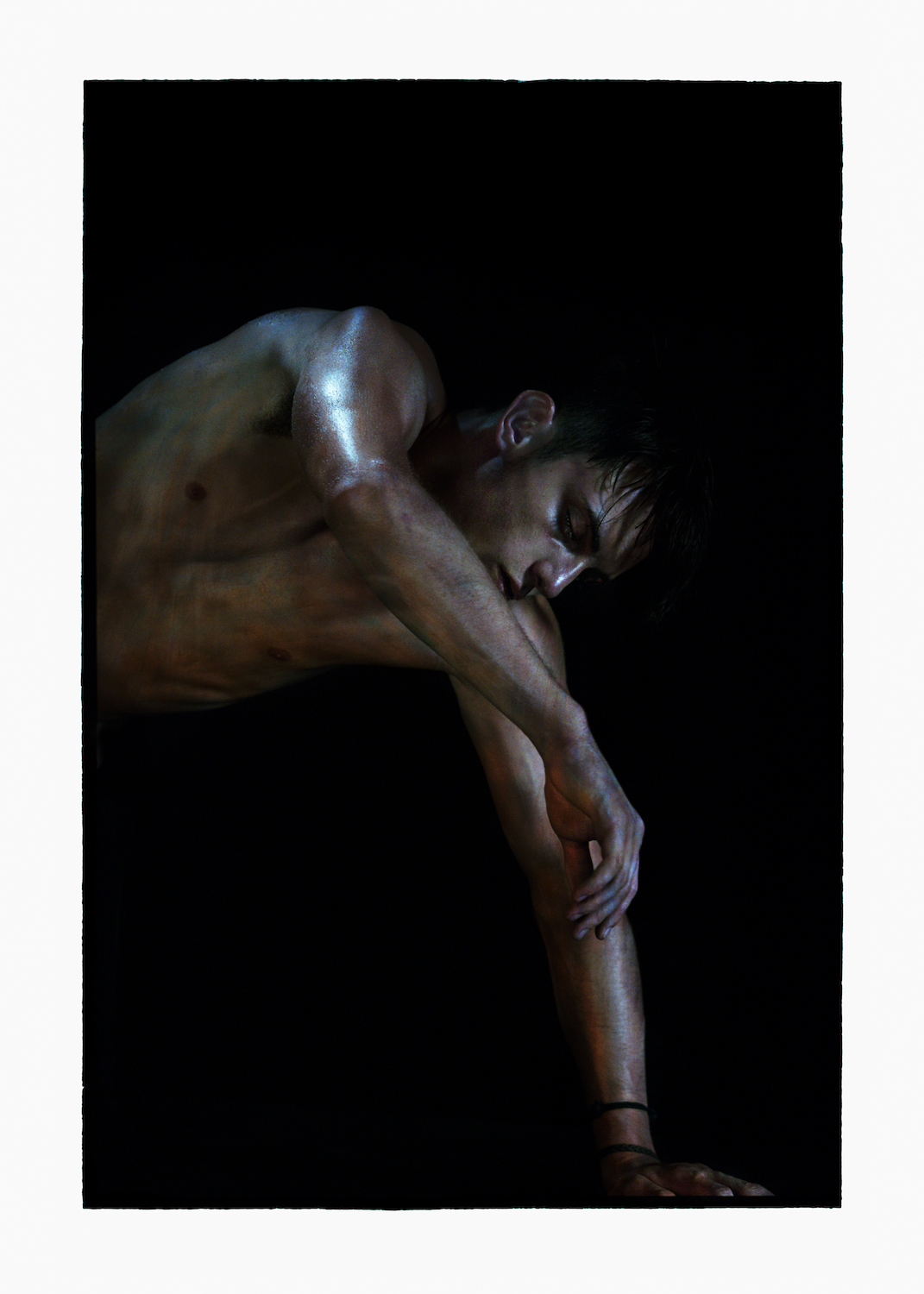

The exhibition is small. Fourteen images, displayed above a black shiny floor, a dark lake that reflects the photographs above so that the viewer, standing back, can see them mirror-imaged. Henson’s preoccupations of the past 30 years, in particular the ‘junkie ballroom’ series from the 1980s, are still here: a juxtaposition of beauty and decay. Young bodies strike classical poses – boys, tender and oiled up, wet and cold, goosebumped and on the cusp – mixed with architectural ruins.

The space between dusk and dark remains. The young men are marbled, statuesque, interior. There is little expression in their faces and their bodies are choreographed to achieve sculptural effects rather than bridging distance with the viewer. Like a Caravaggio or Rembrandt, their bodies and faces are luminous out of the dark space they inhabit. With the rough white framing, though, the exhibition feels uncharacteristically rushed. There is no material available on the images, and the gallery worker informs me that the sheets are just being printed now, that they only received the photographs half an hour ago. The heady, strong smell of ink radiates from the walls.

In the week the exhibition opens, Henson gives a talk at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art on The Wilderness Within: The Body as the Last Frontier. The talk is sponsored by a gin company and as I arrive I’m handed a bespoke cocktail, a mix of gin, rose, pomegranate, rhubarb, with a large sprig of thyme to stir it. I try to drink it as Henson lays out his favourite things.

Working on the “scatter cushion” approach, he starts with A Ghost Story, a film he recently watched three times in a row on a plane to London. Used to Henson’s obscure references to cultural moments I don’t know, my ears prick up at pop culture — “Ben Affleck or the other Affleck in a sheet as a ghost” — and later that night, watching the film, I can understand Henson’s obsession. A ghost of one of the characters (Casey) stands in a house and watches events unfold after his death. The film is still to the point of real-time, the sense of absence marked by the focus on a character who we access only through movement of the body rather than the face; a white sheet and dark pools of holes where the eyes should be, like a child’s vision. This ghost is stuck between two worlds and he longs to inhabit both and never can. In the film, we experience, as Henson puts it, “the interplay between the subconscious and everything else … where the skin ends … a body so expressive and yet so completely anonymous at the same time.”

Henson at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

Henson’s work returns often to a fixation on beauty, believing that “the universe runs on attraction.” Along with the marbled boys, the buildings too are elegant and in shadow, the tunnel in a bridge a gateway to the unknown, echoing the circular frame of a boy and accentuating the notion of peepshow, of Henson’s desire to make you feel like a voyeur, even though he steps back from it – “the absence carefully modulated … It’s there but perhaps it’s not there.”

He plays with horizons as with other boundaries, the line between sky and water as sublime and serene as a Rothko. The reflected dark floor of the gallery echoes the water under the old bridge and I wish for the images on dark, rather than white, walls. If the walls were black, the photographs would bleed into the floor, extending Henson’s fascination with “where you end and the painting begins”.

At the ACCA talk, Henson often goes down a dark alleyway and seems to get stuck in a cul-de-sac. Speaking of Austrian conductor Carlos Kleiber, Henson mentions in passing Kleiber’s alleged sexual assault – the conductor randomly ran from an orchestra rehearsal to a woman in the street and passionately kissed her – and then leads in to the #metoo movement. Henson then explains that geniuses are “in a parallel universe sometimes, they’re not connected to things in the way that they should be” and quotes a comment that one of Kleiber’s musicians made about the great conductor, that “people expect artists to conjure the most incredible things from their imaginations and then to go home and be a nice neighbour and perfect husband.”

As Henson comically uses a German accent here, perhaps to deflect the statement from himself, he looks surprised for a moment that’s he’s told this anecdote at all – and I wonder too why it’s bubbled up to the surface. Like the bespoke cocktail, his talk is a muddled mix of sweet and savoury and sour, elements lovely in their own right, but combined unpalatable and difficult to swallow.

Henson has a mantra that he repeats at every talk he gives, that “meaning comes from feeling, not the other way round”, and this idea is what has always attracted me to writing about his images, that initial bodily response, and where it might lead – the potential for speculative work. But in the latest exhibition, there is no journey, no dark road leading into forest. Henson’s images lack the strength and allure of earlier photographs in the same space. Rather than his stated aim to “forget the boundaries, forget where the parameters are”, his boys, his columns, have become tasteful statues and structures.

As an artist, Henson seems stuck in a groove, in a moment that he can’t get out of. Beyond beautiful objects, his work used to demand more. Approaching a Henson image was about confronting desire and longing, both yours and his and the model’s, filling in those shadows, those things absent from the scene, with your own imagination and feelings: walking that blurry line between the acceptable and forbidden, innocence and knowing.

Henson likes to quote others in the genius mode and settles on Einstein’s idea that “the most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious”. But now, with these latest images, there is no mysterious threshold. The works have well and truly stayed on this side of that blurry line. They have attained the status of exquisite objects. As the man says when he gets off the phone, “We’d like to purchase this one.” The man points to the only image that I’ve lingered in front of, a boy draped, hanging between thought and feeling, caught between two worlds.

“The boy. He’s beautiful, isn’t he? Don’t worry, I’m sure we can make room on the wall for it.”

Bill Henson’s current exhibition at Tolarno Galleries, Level 4, 104 Exhibition St, Melbourne, runs until 2 June. Phone: +61 3 9654 6000.

Kirsten Krauth is a writer and editor based in Castlemaine. Her first novel was just_a_girl and her second-in-progress is set around the twilight worlds of Bill Henson and Nick Cave in 1980s Melbourne.