Out in the Camperdown sun I’m sitting with Michael Mohammed Ahmad, drinking peppermint tea and long blacks and talking about his latest novel The Lebs. Earlier I had listened in as he wriggled through a particularly scrutinising interview in which the interviewer demanded he explain why he wrote a book that unashamedly represents misogynistic, sexist, racist, violent behaviours.

The interviewer told him, “I certainly couldn’t put it down, but I can’t say I enjoyed it. I found it very, very confronting.”

I put this word to Mohammed again – confronting – and asked him why he believes this has been one of the primary reactions to his book.

He fixes his cap so it’s on backwards, and runs fingers through tidy facial hair. “The problem is some people think the dumb Leb in the book is the dumb Leb who wrote it.”

He finds it ironic that Tim Winton’s new book The Shepherd’s Hut, a story about Australia’s culture of toxic masculinity, is a number one bestseller while he is beating off flak for the content in The Lebs. “It’s funny,” Mohammed says, “because isn’t my book essentially doing the same thing?”

Mohammed speaks swiftly, as though he’s catching up with his brain, which is jammed with cultural theory, literary references, and economic cutthroat slices of wisdom. “If you’re born as an Arab in the world today you’re brought up in an environment that is antagonistic and confrontational and constructs you in a particular way. For people to be offended or freaked out or confronted by the work – well, stuff it, that’s my day-to-day reality.

“You can’t learn about me from Peter Dutton,” Mohammed says. “My book is the real entry point, a self-determined act by a Leb. I don’t sugar coat. I’m not ashamed to talk about the homophobia, misogyny, sexism, patriarchy and the violence that arose from my community.”

The Lebs tells the story of Bani Adam, a Lebanese-Australian Muslim boy and wannabe writer growing up in Western Sydney in the lead up to – and the aftermath of – 9/11. Think of it like Charles Bukowski’s Ham On Rye set in Punchbowl.

Readers were first introduced to Bani as a seven-year-old boy in Mohammed’s debut novel The Tribe (2014). But it’s really in this book, his second to be published, that his ruminations on cultural identity have bloomed.

Apart from being Mohammed’s fictional alter ego, Bani is an egotistical romantic who feels at odds with the other boys at Punchbowl High. All their lives centre on the claustrophobic school, barricaded with “nine-foot fences with barbed wires and fences”, imprisoning them and functioning as a very easy-to-pick-up microcosm for Aussie society today.

“If you look at the micro-lens of this novel, then it’s about the Lebs,” Mohammed says. “But if you read outside the book, it’s about the broader Australian context that creates the Leb identity.” Using the power of absence as literary device, by having white Australia physically, spiritually, and ideologically absent in the novel, he asks the reader to consider how the forces that try to govern these communities have any legitimacy when they are seldom present within them.

Bani’s disaffected classmates resort to violence, exaggerated macho-ness, and sexual conquests rather than pursuing any sincere interest in their studies: “There are no questions about Tupac in the HSC.”

Michael Mohammed Ahmad at a Sweatshop event. Photography by Chris Woe. Image courtesy of Michael Mohammed Ahmed.

There are so many sequences of juvenile behaviour written in Mohammed’s ceaseless prose that the reader witnesses what becomes a monotony of stabbings, punch-ups, racial slurs, and all-round nihilistic arseholery. A Pacific Islander stabs a Lebo for stealing his Nokia; the students insult the teachers (“Maybe your ancestors came from apes but ours didn’t”); and so-called ‘mates’ steal each other’s girlfriends and dispose of them without an inkling of emotional attachment.

“This is an autobiographical work,” Mohammed says. “It’s fiction, yes, but I’ve based it on my real-life experiences, and I can’t apologise for that. If you think reading the book is confronting, then try being a Leb – try being a 14-year-old male Leb during September 11, when the gang rapes were taking place and splattered across newspaper front pages, and we had become the main threat in Australia.”

The novel is told retrospectively by an older Bani who looks back on his schoolboy years as though he’s reliving them all over again. It proceeds like an inner monologue, an unfiltered glimpse into Bani’s world. But by anyone’s standards, Bani is freakishly well-read, quoting from William Faulkner, Vladimir Nabokov, and James Joyce. He wants “to be a great novelist like Tolstoy and Chekhov, and shape reality through my own words . . . not a Lebo – I am above it.”

Mohammed himself is now a young writer in his thirties, a new father and, interestingly, married to a white Australian woman. “My son’s mum is whiter than Pauline Hanson.” Looking at his writing in The Lebs, he says, “I’m ironically performing a kind of stereotypical trope to scare racists and orientalists… I get off on that,” he says. “But of course ‘irony’ only works if you don’t have to explain it.”

Separated into three acts – ‘Drug Dealers & Drive-Bys’, ‘Gang Rape’ and ‘War on Terror’– the novel deconstructs the obvious stereotyping of the titles. The first act by directly addressing the violence of the schoolboys. The second by portraying the naïve sexual pursuits of horny Muslim male youth who collect blowjobs like Tazos. And finally the third act, which deals with Bani reconciling his “underprivileged, marginalised working class community with the white left arts community that enacts crazy, racist, hypocritical white supremacist nonsense that they don’t even know they’re enacting.”

Yes, there are a lot of nasty views and personalities in the book. But hell, your local all-boys Catholic private school is a sexist, homophobic, misogynistic breeding ground, too. According to Mohammed, any assumption these vices are symptoms of a particular cultural demographic is essentially a “very clever way that powerful white men pigeonhole and scapegoat [others] to hide their own misogyny. Just look at what’s going on in Hollywood: it’s these rich white men behaving like the fucking dumb Lebs from Bankstown.”

He nonetheless confesses he’s “only as smart as his reader”, and that much of what should be taken away from this novel lies beneath its chaotic surface. “If people are going to snub [the book], saying it perpetuates Arab stereotypes, that it’s misogynistic and homophobic and offensive and ‘I’m offended’ – if that’s your surface reading of it, then I’ll be reduced to an idiot.”

He breaks off our conversation to fix his cap again and take a sip of water.

“Wait, which cup’s mine?” he asks.

“I don’t even know,” I say.

“Have you…?”

“Yeah, I drank from one of them.” We both look between two even layers of water.

“Oh man,” he says, putting cup to lip. “Now it’s like we’re kissing.”

Mohammed is sharp and funny, taking-the-piss when you least expect it. He thinks white Australia often misunderstands and dehumanises his community. For example, when a bunch of kids pose for a newspaper, throwing out gang signs and the middle finger – they’re usually just joking around. Unfortunately our society knocks the joke back onto them, simply because it’s not in on it.

Starved of a creative community growing up, of a way to either articulate or make sense of their reality, Mohammed and fellow author Peter Polites founded a Western Sydney literacy movement in 2006 that became known as the ‘Sweatshop’ collective. Supported by Westwords and Western Sydney University, it’s responsible for some of Australia’s most exciting emerging voices. In The Lebs, Polites appears as Bucky, a writer comfortable in his own skin. It’s Bucky who helps inspire Bani’s own self-discovery. Anyone intrigued by Mohammed’s writing should also read Down the Hume by Peter Polities; the novels echo each other.

Maybe one of the most important ideas to take away from Mohammed’s book is found in its subtext, not the metastructure of the novel. “What I’m arguing in my book is [that] the term ‘Leb’ is a brand new hybrid Australian cultural identity. There are Indonesian, Palestinian, Jordanian kids identifying as Lebs,” Mohammed says. “It’s our new metonymy of looking at the new ‘other’.”

“The basketball court becomes the closest landscape to an Arabian desert the Lebs of Punchbowl Boys have ever known,” Bani observes in the book. “Don’t mistake the Lebs for ‘people from Lebanon’.”

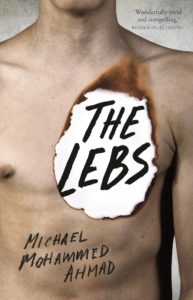

‘The Lebs’ by Michael Mohammed Ahmad (Hachette)