Dear Nutri-lame,

One day my kid came home and chugged a litre of milk. Then he made an omelette. Six eggs. Then he went back to the milk. “What the hell are you doing?” I asked. “Bulking,” he said. “Trying to get SWOL.” “What the hell is SWOL?” “Ripped,” he said. Then he asked if we had any Nutri-grain. “Nutri-grain is rubbish.” I said. “Nutri-grain. More like Nutri-lame!” “You’re such a loser,” my kid said. “Takes one to know one,” I replied. He walked out of the room.

But that afternoon on the way to the shops my kid couldn’t stop talking about it. He told me about Kevin and how Kevin was all muscly now. Before he’d been all normal and skinny but now he was huge. “… and Kevin eats Nutri-grain EVERY DAY.”

So we got the cereal. We returned home. My kid sat at the kitchen table and began shovelling the cereal into his mouth. He shovelled one bowl. Then he shovelled another. told me he wanted to be big like Kevin was big. He wanted to be an Ironman like the ones he saw on the TV. “So do some push ups,” I said. He told me he had. He said he’d been doing them every night before bed. And sit ups too. And during the day, at lunch, he’d been running around the oval. “I fucking hate, Kevin,” he said. And then he told me it wasn’t fair. “Why can’t you just be cool like Kevin’s dad is cool?” Kevin’s dad sounds like a bozo, I told him, and then I opened the ashtray that I’d converted into a swear jar and told him to put another dollar into it.

We walked through the supermarket. “Okay let’s make a deal,” my kid said. “If Nutri-grain has a 4 star health rating, we get the cereal.” I laughed. “Nutri-lame is basically junk food. You got no chance.” “Do we have a deal?” “Wait,” I said. “What if I win?” “I don’t know. What do you want?”

I thought about it. Then I told him I wanted a son who thought independently and spent less time on the Internet. “Deal,” my kid said, grinning, immediately pulling out his smart phone and Googling: Nutri-grain health star rating. “Four stars, motherfucker” he said, showing me the screen. Then he started waving four fingers in my face. “Smell that?” Jesus, I thought. Was he going to – “Smells like victory.”

“Let me see that,” I said, snatching the phone from his hand. It seemed impossible, but, no, there it was. Four stars. He was right. We say, “Mother trucker,” I said, opening the swear tray again.

So we got the cereal. We returned home. My kid sat at the kitchen table and began shovelling the cereal into his mouth. He shovelled one bowl. Then he shovelled another. “I’m going to start calling you ‘The Shoveler’,” I said, but he wasn’t listening. Too busy shovelling. That’s how you do it, I thought. Just keep shovelling. Life: a constant shovel towards something, and then death. Just joking!

Except what happened next is no joke at all. My kid started complaining. He said his stomach hurt. “Harden up, legend,” I said. But he wouldn’t harden up at all. So there’s my kid groan-sleeping on the kitchen tiles when one of your Nutri-grain commercials came on. You probably know the one. It’s the one where the music sounds like robots are fucking, then murdering one another. Then an athletic male starts, for no reason, running and flipping and spinning on the side of a GIANT CEREAL BOWL, eventually scaling a GIANT NUTRI-GRAIN BOX. And then he summits the box and raises his hands above his head, screaming as if coming down from the sugar high induced by your cereal, or meth.

As you’ve probably gathered, I’m a chill guy. On a good day my kid would even tell you I’m a cool dad. Well, he’d say, “My dad’s a fuckwit”, and I’d say, “My kid was adopted” and he’d say, “Knew you didn’t have it in you” attempting to punch me in the testicles, and I’d say, “Losersaywhat?” and he’d say, “What?” and then I’d make a circle with my pointer and thumb and hold it beneath my waist, and when he looked he’d say, “fuck nugget” and then I’d sock him in the arm, reminding him afterwards that he owed two more dollars to the swear tray.

What I’m saying is that we understand each other. But you know what I don’t understand? Why my kid was reeling on our kitchen tiles after consuming several bowls of your four-star cereal.

Now a normal family would say: Interesting… very interesting result from the cereal. Perhaps we should limit the food’s intake – and I use the term “food” loosely – thereby avoiding similar outcomes in the future, but as I mentioned before I am a cool dad. I let my kids make their own mistakes. Besides, I figured if my kid wanted to get ripped and become an Ironman then who was I to discourage him? After all, your cereal is, and I quote, “ONE OF THE HIGHEST PROTEIN CEREALS”.

But over the next month something strange started to happen. My kid got bigger. But it wasn’t the big he was after. Now, he was just fat. “I’m fat!” my kid cried out one morning, staring into the mirror. I heard him from the kitchen.

“What’s that, SWOL LORD?” But this made him cry out even louder. “I feel like a sack of shit,” he said. “And look at my face.” So I did. And it was true. His face looked terrible. Once it had been smooth, but now it was blotchy and rough, as if several fault lines had cracked deep within to produce volcanos, and those volcanos liked to party. Then my kid looked at me and said, “I hate this. I feel so bad” and he put his arms around me and began to cry. He cried and he cried and I patted his back and told him it was okay. I told him to let it out. Then I strung together a confused metaphor that turned out not to be a metaphor about how you couldn’t use sugar as a cleaning product, unless it was Coke and you were cleaning a stainless steel bar. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said, between tears. “I just wanted to be strong.”

Now let me ask you this: where do you get off? Can you hear my beautiful boy crying? Can you hear him whisper-crying, “I just wanted to be strong”? My kid was in training. He wanted to be an Ironman. He wanted to be unstoppable like the extremely hot-athletic people found in your advertisements. But if he continues like this I fear he may become something else: a diabetic. Because your cereal is full of sugar! Sure, a big deal was made when you reduced the sugar content a few years ago, but it’s still plenty sweet. 26.7g per 100g to be exact. Four stars?! Yeah right. Food for barge-arses! For bozos!

For this, I place a curse on you, Nutri-Lame. You have now been cursed. May it bring rain. May it bring sheets of fat into your dreams and into the dreams of those you love.

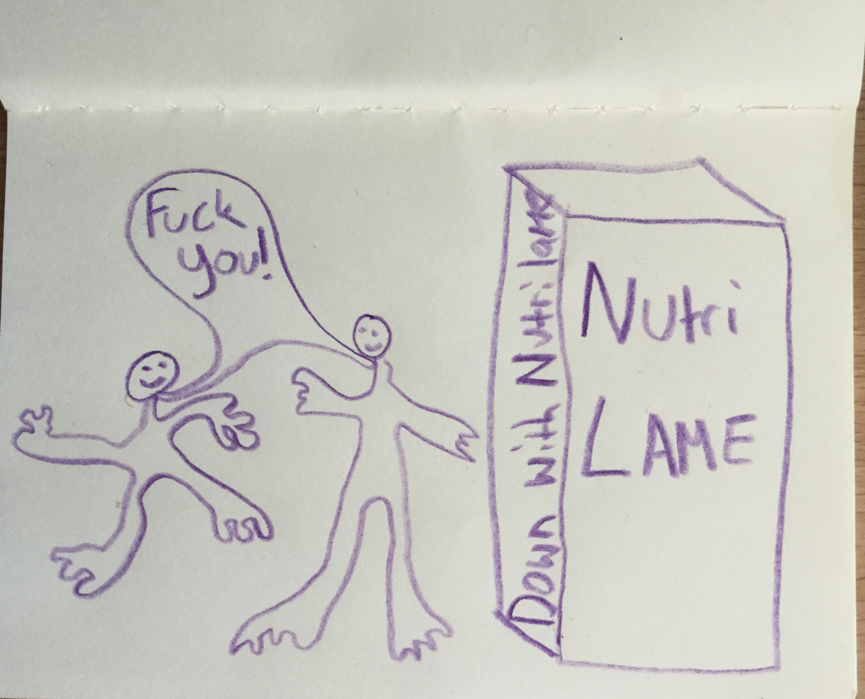

Oh, but like all great literature, this tale has a twist, a silver lining if you will. Have you seen that movie Silver Linings Playbook? Don’t bother. It’s rubbish. Instead, view the drawing below as your very own silver lining playbook. For in these times of great suffering my son and I have banded together. We have become strong. We have grown. Instead of testicle punches, we hug. We talk. We have ‘feelings Tuesday’ and we talk about our dreams on that day. We jog. We go to art class. And then we draw. Please find, enclosed, an original collaboration we’ve titled Thank You. Hang it on your wall, Nutri-lamers, and your curse will be lifted. Hang it on your wall and set yourself free!

‘Dear Nutri-lame’. Artwork by Oliver Mol and family.