I see the billboards all over town. They make me dream of something. I guess that’s their purpose: to entice me to see the film. Some dumb Hollywood romance. Why should that appeal? I’m not quite sure. But I am thinking tonight, after taking a walk beneath a nearby railway overpass to photograph one of those billboards, that I saw a glimmer of something else.

I start to think about the nature of what I have been receiving about male identity on social media and alike lately. Which is largely to say that straight white males are, by their very essence, violent, polluted and disgusting beings.

Around me I see and hear parents worrying for their sons – and their daughters – and what this pathological shift in the conversation means. One might hope it cultivates more peace and tolerance for all, but some perverse degradation of boys seems to be growing like a cancer. And with it a future hopelessness when it comes to any reconciliation between, let alone beyond, genders, not to mention a word like ‘love’ mattering.

A Star is Born will hardly change that. Even so, it is already one of the biggest films of the year. And what is popular entertainment if not a distraction from, or an affirmation of the forces within and around us? As a restorative to romance, A Star is Born does bring something special to the table despite its slightness of form. Though ‘restorative’ is the wrong word once you’ve watched the film; perhaps ‘provocation’ is better?

With fortuitous timing, it has something powerful to say about ‘toxic masculinity’, painting an unusually believable portrait of male energy hedged between self-determination and self-destruction. And the ways in which women might suffer in the shadow of that existential struggle, or find their own costly liberation.

Jackson Maine (Bradley Cooper) and Ally Campana (Lady Gaga) make music together in ‘A Star is Born’. 2018.

From the moment the film opened, I sensed a very different beast to the so-bad-it’s-good expectations I had been willing to settle for. Maybe I’d been imagining an earlier version when Beyoncé and Tom Cruise were being mooted for the lead roles. What a brilliant car wreck of egos that might have been!

In a time when Marvel superhero movies dominate the box office, and more sophisticated alternatives slant toward indie cinema, A Star is Born emerges as a genuine oddity: a mainstream entertainment for grown-ups. It does not feature robots, explosions or James Bond; nor does it subject us to purely brutal sojourns or weird, sardonic riffs on pop culture. It is, as advertised, a great big romance with a bunch of great, big songs.

What should have been entirely clichéd, even generically camp, punches above its multiplex weight to leave you surprised and even moved. A Star is Born is a film I will remember for the rest of my life. And that, I really did not expect.

Now, of course, it’s hard to imagine anyone else but Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper as our star-crossed lovers. In this fourth version of the story, Gaga and Cooper inherit a mantle that began with Janet Gaynor and Fredric March (1937) and continued with Judy Garland and James Mason (1954), before reaching a grandiose blowout of sorts in the Laurel Canyon era with Barbra Streisand and her ex-boyfriend Kris Kristofferson (1976).

While every one of those performances is memorable, it’s Garland who towers like some sacrificial goddess over the film’s history, not to mention its histrionic impact.

It might be of interest to note the Streisand-Kristofferson vehicle was co-scripted by the husband-and-wife team of Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, never shy of a drink himself, nor unversed in having to cope with his wife’s rocketing literary reputation and his own second ranking. Streisand and her then husband Jon Peters meanwhile co-produced the 1976 film with a much cooler eye on her career. If we return to Garland’s anxious, erratic brilliance in what was then her pilled-out ‘comeback’ role, or Streisand’s excessively patronised control over all her life and work (manifest in critical attacks on her for everything from her singing to her perm and her nose), we see how A Star is Born has always functioned as an autobiographical echo chamber for whoever gets involved with it.

All these versions run with the same basic narrative themes. A fading male superstar discovers a budding female superstar. Will the tensions of their rising-and-falling career arcs destroy their love? Or will their love for one another compromise their artistry? Or is it inevitable that one must survive, even thrive at the expense of the other?

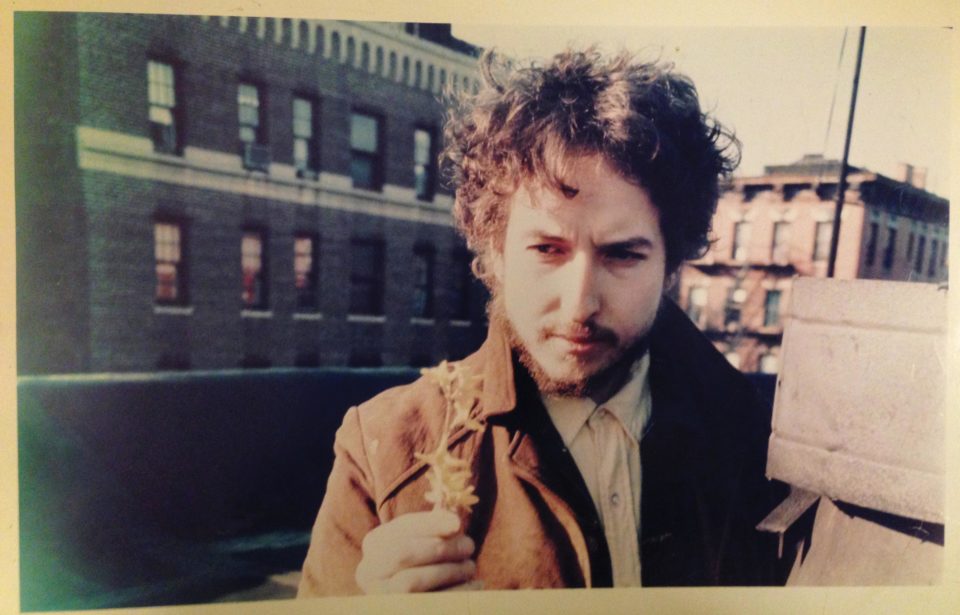

Bradley Cooper as Jackson Maine in ‘A Star is Born’. 2018.

In keeping with its romantic outlines, A Star is Born hits the box office in numerous ways: as a date movie; a generation-bridging remake you can take your mum to; a proto-feminist fable; and a bastion of gay culture and its obsession with musicals and anything with a smidge of melodrama. Promoted as a vehicle for the 32-year-old Lady Gaga in her feature debut as an actress, the film underlines her major pitch for a place in the gay pantheon beside Garland and Streisand. It also pays off her obvious debts to Madonna – and takes Lady Gaga to a planet her cultural precursor never reached. While I don’t think Gaga will get an Oscar for her role, she might well gain a nomination and enjoy a very good evening at the Golden Globes along the way.

Pastiche can seem like a very limited art. It owes more than it gives, even steals. But now and again the recycling can bring you to something wonderful. A Star is Born works in this way, taking the best of the previous films and throwing away what doesn’t work. It’s all the better for doing that job sincerely. There’s no winking at the audience; no sly ironies or glittering brashness. The whole thing is executed as if this were Romeo and Juliet – in ecstasy, then struggling to the death for their love.

Bradley Cooper both stars in and directs the film. A breath-taking achievement. He was mentored in some vaguely inspirational way, perhaps, by Clint Eastwood, who invited a then reluctant Cooper to be the film’s lead almost eight years ago. Eastwood was slated to direct, but the project languished in ‘development’ and the granite fox of Hollywood moved on. Whispers of this director and that star continued as the whole thing tilted away. Cooper dealt with his father dying, became a major star (best known for his leads in Silver Linings Playbook, American Hustle and American Sniper) and felt ready for a role he’d formerly believed he was too young to pull off. It wasn’t long before Cooper took over completely to make it happen. It’s now the first step in what will clearly be a very important directorial career for the 43-year-old star.

During filming, Cooper would become a father himself; Lady Gaga would lose one of her best friends to a long-running battle with cancer, rushing to her death bed on the day she was slated to perform the very last song of the movie. Her friend died only minutes before she reached the hospital. Gaga was encouraged by her friend’s husband to return to the set of A Star is Born and sing ‘I’ll Never Love Again’. As a closing performance, it is a grieving stunner, a double goodbye – to her beloved in the film and her beloved beyond it.

Ally (Lady Gaga) takes the stage in ‘A Star is Born’. 2018.

A Star is Born begins with country rock star Jackson Maine (Bradley Cooper) throwing down pills and a tumbler of bourbon before he strides on stage to feedback and launches himself into a swaying, heavy song he calls ‘Black Eyes’: “Black eyes open wide / It’s time to testify/ There’s no room for life / And everyone’s waiting for you… By the wayside / By the wayside.”

The energy of the music, the knockdown lyrics and the cinematography could be out of some imaginary documentary for Neil Young’s Crazy Horse. I’d almost have been happy to watch this play out as an entire concert on screen. Hearing the soundtrack album later it’s enjoyable, yes, but I’m surprised at how much more urgent the film made everything seem. As Jackson Maine, Cooper made me feel like everything was right on the line. And the lyrics for ‘Black Eyes’, well… they’re suicide ideation in spades.

Let’s face it, with a few exceptions (David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth; Ewan McGregor in Velvet Goldmine or Joaquin Phoenix in Walk the Line), the territorial cross-over between musicians and actors has usually been embarrassing. Required to act, most singers are stiff as cardboard, boxed-in by a narcissism they can only release live on stage; as pretend musicians, actors come off like ballet dancers trying to be boxers, no force behind their poses.

A Star is Born transcends those dilemmas. Cooper has stated he tried to draw inspiration from Pearl Jam’s Eddy Vedder for his on-stage performances as Jackson Maine. He’s done okay by his musical hero. The actor spent two years taking vocal lessons, reckoning his voice deepened by almost an octave to meet the demands of filming.

His newly minted baritone was about more than just the singing too. When he arranged a meeting with fellow actor Sam Elliott, Cooper played him a tape to try and persuade him to take part in the film. “This is going to sound weird,” Cooper told him. What Elliott heard when Cooper pressed ‘PLAY’ was someone who’d spent the last six months with a dialect coach trying to sound very much like him. Elliott was flattered and impressed. He accepted the role of Bobby, Jackson’s manager and older brother, a failed musician who had brought Jackson up on the road and taught him everything he knows.

The acrimony and frustration that almost drowns out their brotherly love is one of the finest depictions of repressed male empathy I’ve seen on film; saying too little, yet communicating so much. When Jackson finally confesses to Bobby that it’s not their father he admired, it’s him, there’s a deluge of feelings in Sam Elliott’s red-rimmed eyes and panicked turn of a wheel as he reverses away from the conversation in his car. It is simply too much pain and love in one damaged lifetime to absorb.

Jackson Maine (Bradley Cooper) and his brother Bobby (Sam Elliott) in ‘A Star is Born’. 2018.

Not un-coincidentally, the band Jackson plays with in A Star is Born is Lukas Nelson and The Promise of the Real. Nelson is Willie Nelson’s son, though his group is more lately known for being Neil Young’s backing band, a job description Pearl Jam have likewise filled in the past. All the concert scenes are 100% as they happened, live performances filmed as a warm-up act for Willie Nelson and various other rock ‘n’ roll connections, among them Kris Kristofferson, who gave the band four minutes of his own set time at Glastonbury to do their thing for the cameras. This level of musical authenticity pays off. The band smells of the road, with a shot glass full of Cooper’s genuine stage fright for added edge. In the meanwhile, Lady Gaga insisted all vocal performances be live-to-film, not lip-synced. She could do it, could they? The whole thing comes alive as a result.

It’s also clear Cooper owes a lot to Kris Kristofferson’s fragmenting take on rock stardom in the 1976 version of A Star is Born, and even more to Jeff Bridges’ Oscar-winning turn as Otis ‘Bad’ Blake, the booze-ruined country singer in Crazy Heart (2009). Putting those roles beside Cooper-as-Jackson now, Kristofferson could be his older brother and Bridges his father in some mash-up on YouTube.

When Jackson staggers into a corner bar, desperate for yet more to drink after the hyper-charged ‘Black Eyes’ stadium show (a song written by Cooper/Jackson and performed by him before a very large audience for the first time) it turns out to be a nightclub hangout for drag queens. Among the film’s early reliefs is us not having to deal with the cliché of a straight guy who can’t cope with a gay scene, especially when that guy is an alcoholic, drug-fucked rock star. One of life’s natural born explorers, Jackson’s delighted to have a glass in his hand and enter another world.

As the waiting-to-be-discovered nightclub singer Ally Campana, Lady Gaga is, of course, the main attraction of the drag show. She’s the only girl they’d let do that, something she later explains is “an honour” for her. As Ally, she struts through the crowd and lounges across the bar in front of Jackson, cycling her legs in the air and generally rejoicing in Edith Piaf’s ‘La Vie En Rose’ as well as sporting Liza Minelli’s eyebrows, a tribute of sorts to Garland. It was a performance of this song as Lady Gaga at a charity benefit two years previous that convinced Cooper to cast the singer as his leading lady. Art imitates life imitates art…

Jackson is inevitably besotted by this unknown talent, though Cooper-as-Jackson does lay on his starry-eyed beguilement a little thick. As you might expect, Gaga feels similarly unsteady in these early scenes, overdoing things or stumbling in a way that seems less like ‘acting awkward’ and more like ‘I’m-just-not-sure-what-to-do-here’. But whenever things do threaten to get a little hammy or clumsy with either actor, there’s a feeling of voyeurism that jostles your reservations. It’s as if we’ve been dropped in a little too close for comfort to something hyper-real – and are seeing the way we tend to act in self-made movies about ourselves whenever we get caught up in romance. It’s that most wonderful of movies: up all night talking, falling in love. Even the late-night Super ‘A’ Foods store is magical, its car park like some neon stage set for Ally to perform acapella, a bag of frozen peas strapped to her bruised fist for extra perfection.

Lady Gaga in girl-next-door mode as Ally Campana in ‘A Star is Born’. 2018.

Cinematographer Matthew Libatique takes this intimate reality further by keeping the screen focus very tightly on the actors throughout. Best known for working regularly with Darren Aronofsky (Black Swan and Mother among others) he brings the same intense closeness and physical presence to this much more mainstream Hollywood fable. When Cooper is playing drunk you can almost smell the alcohol sweat; touch his matted hair. Lady Gaga sans make-up is given no room to escape; it’s bold of her to reveal herself so; and she grows mightily in girl-next-door charm and presence across the film. When she does drop into her more theatricalized pop style you’re confused as to which aspect of her you prefer. The ‘real’ Gaga being her girl-next-door self, or the ‘artificial’ Ally that is becoming a total performer? The truth is Ally, like Gaga, has roots in drag shows and relates to Piaf and pop music as much as any of Jackson’s ‘authentic’ alt-country dreams for her.

A viewing of the recent Lady Gaga documentary, Five Feet Two (2017), which went behind the scenes for the creation of her album Joanne, only adds to the echo-chamber effect. With Joanne, Gaga took on a more countrified style, all pink Stetson hat and attitude, her mission on the album being to reveal the real Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta. In other words, Gaga had decided to perform herself. A Star is Born continues this ‘real’ direction for her, which only makes feminist critiques of the film seem misplaced when they attack Jackson’s dreams for Ally being authentic as some patriarchal imposition from Cooper the director. In fact, what we see is Ally learning to act the star and control the degree of her performance, in terms of both its authentic and synthetic nature, a division of understanding Jackson could never make. A star is born, alright – in a hall of mirrors.

For the first half of the film Ally will embrace Jackson’s rootsier world. Her bedroom will show a Carole King poster; as her confidence grows you’ll maybe get a glimpse of Stevie Nicks and Rickie Lee Jones in her heart as well. She’ll confide in Jackson about her inability to get breaks in music because of her nose and how ugly she was made to feel whenever industry interest had circled around her. Creating songs with Ally, dueting with her at his shows, Jackson shoots her straight into the spotlight with him. Then Rez Gavron (Rafi Gavron) turns up with all the smoothness of a shark in the water, an English producer and star-maker who sees her potential rising “way beyond” where she and Jackson are at. Ally will ultimately determine her own direction.

Jack (Bradley Cooper) and Ally (Lady Gaga) on tour in ‘A Star is Born’. 2018.

Strange echoes lap at the edges of the story: Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love; Michael Hutchence and Paula Yates; Keith Urban and Nicole Kidman… A Star is Born seems to reside in between the darkest and most powerful of rock ‘n’ roll myths and showbiz rehab clichés. Yet these legends and celebrities reemerge in your mind as human beings with real pains and aches as you watch the film. The gods are people too, after all. It sounds trite, but it’s easy to forget.

We will learn that Jackson’s 18-year-old mother died in childbirth. And that his father was a talented musician and self-annihilating alcoholic who drank himself to death while Jackson was in his early teens. A devastating account of a suicide attempt as a 12-year-old, told quite comically, and thereby very realistically, explains a lot about the suffering Jackson still carries inside him. He begins to take on the energy of a lion breaking down. The steady decline of Jackson’s hearing as his tinnitus worsens only adds to the feeling of a man losing his grip on everything that matters. He can’t even hear his own guitar playing any more. Cooper does a great job of presenting Jackson post-rehab, stripped of his carapace of alcohol and braggadocio, nothing but bright nerves and mortal shame for his behaviour. In the growing sense of the film those early scenes depicting Jackson’s worship of Ally start to make a lot more sense retrospectively. He’s a lost boy looking for an angel. And he believes he has found one in her.

By contrast, Ally was raised by a loving, even adoring Italian father (Andrew Dice Clay) who has overcome his own alcohol problems, though not his affable illusions of having been a singer who was once “as good as Sinatra”. She also has a fleet of flawed, but amusingly decent male role models around her due to the fact her father works as a professional driver and chauffer. It’s hazy where her mother might have gone, but the role play is clear: Ally’s a carer, a proxy mother to her boy-father.

The nice thing about A Star is Born is it does not overplay these character set-ups to the point of hysterical messaging. Any archetypal forces are influences, not jail terms defining identity. Ally’s father is also trying to dream her free of him to make her fulfil her talent; she’s let the industry dent her confidence and hangs on to where she feels needed most. Transposing her attention from her father to Jackson is one way she can cross that bridge. But there’s a lot of strength in Ally, a lot of ambition nonetheless. Conversely, when Jackson smears a cream pie in her face, jealous of her advancing stardom and changes in her music, Ally laughs it off as a funny reminder of her artistic vanity (later they will use the same gesture at their wedding rather more lovingly). Yet you sense her laughter is a skilled defusal of something darker and more malicious in Jackson’s injured male pride. There’s never a clarification of that. Time and again, as the director, Cooper leaves the audience to interpret a scene rather than be confirmed one way or another in its meaning. The truth, of course, is that many things can be true at once. And some things are never clear.

Along with Andrew Dice Clay, Cooper has cast another comedian against type in a vital dramatic role – Dave Chappelle as an old friend and ex-muso called Noodles who hauls Jackson’s drunken body from the kerbside flowerbed out front of his family home. It has the feeling of this-has-happened-before. Chappelle is a revelation – subtle, amused, non-judgemental, but also firm, the guy who has your back and tells you little truths quietly. He tries to explain to Jackson how his own domestic bliss has come from staying put and coming to recognize how happy that has made him. Noodles has stopped running from himself and found his dream was altogether humbler and closer than he ever realized. He just had to grow into it. Inspired by Noodles, Jackson loops a steel guitar string into a wedding ring and proposes to Ally when she flies to be with him.

It can’t last. Jackson can’t get to that full wisdom that Noodles has tried to impart and Ally offers. He is too caught up in alcohol – and the agonies of his upbringing. He remains, forever, his drunken father’s injured son. A lost boy undeserving of love. To Jackson’s way of thinking a sacrifice is needed. And she will be the one who shines on without him.

Billboard, ‘A Star is Born’, Sydney. 2018. Photography by Mark Mordue.