“[Jack] took another job, which promised more money, but it didn’t last long and he found himself out of work. This didn’t bother him at all. He still had money in the bank, and anyhow it was easy to borrow from friends. His indifference was the consequence not of lassitude or despair but rather of an excess of hope.” – ‘Torch Song’, John Cheever.

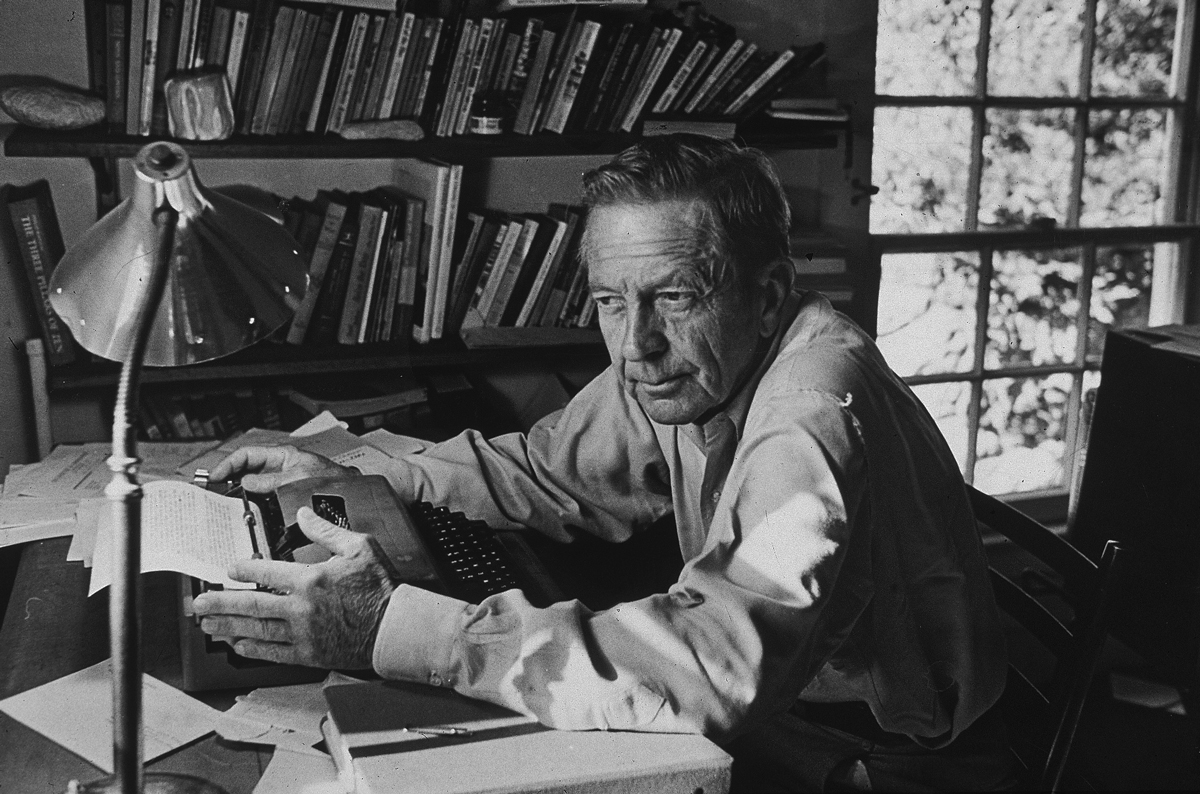

It was early 1977, and although John Cheever was not yet bowed by cancer, it wouldn’t be too long before he was. Within five years, he would be a cadaver lying in a bed, naked save for a white, hard plaster cast cocooned around his right leg. He would take his last breath surrounded by family, and then, when he breathed no more, his son Benjamin would leap up and try vainly to resuscitate him, his lips forming a seal around the dead man’s mouth.

After Cheever’s passing would come the sorting of his papers, and Benjamin would then discover the extent of his father’s homosexuality. The numerous affairs would be detailed in secret correspondence, and the rest would be filled in by Cheever’s friends and lovers.

The composer Ned Rorem would tell Benjamin that for Cheever, orgasms were always “accompanied by a vision of sunshine, or flowers”, and though Benjamin would first be surprised – troubled, even – by the stories of his father’s sexual habits, he would eventually come to write of them in the kind of cool, clean prose Cheever himself would have been proud of.

But that was still five years off. It was ’77, and John Cheever was, for the first time in a long time, a name worth dropping; an author to be mentioned in casual conversation by first year literature students keen for attention, his name swilling around their mouths like a rich gulp of red wine. The “Ovid of Ossining” the critics had once called him, and now they were calling him it again.

His books, having long before dropped out of print, were suddenly resuscitated. The press circled like sharks, and his craggy, serious face appeared on the front cover of Newsweek. “A great American novel,” intoned the yellow letters of the headline beside his head, and the placement of the typography and the stern look on Cheever’s face made it seem like he were the novel in question; as though he were a leather-bound American classic, ready to be pored over.

It was Falconer that had done it. The novel, Cheever’s fourth, was a runaway success. It spent three weeks on top of the New York Times bestseller list, and sparked enough renewed interest in Cheever’s work to warrant the publication of a collection of his short stories, which too were rapturously received, and which, within a few years, won him the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

After years of alcohol abuse, and poor sales, and cruel critical notices, John Cheever was suddenly as successful as any American writer of that era could hope to be. He had, to his quite genuine surprise, been blessed by the universe with that most mysterious, most desirable of currencies: happiness. And then, midway through 1977, while teaching at Utah university, Cheever met a young creative writing student named Max Zimmer, and his life changed again.

Falconer by John Cheever

The first time was in a motel room. They were laying on a bed together, when Cheever, always the aggressive flirt, guided Zimmer’s hand towards his own crotch. Zimmer pulled away. Like many of the others on the receiving end of Cheever’s affections, the young man later tried to pretend nothing had happened, but privately reeled with what he called a kind of “confusion and revulsion.”

It was complicated for Cheever too. Embracing Zimmer in the motel doorway, Cheever breathing in the young man’s ear, the author felt both “a stirring of love” and a hot, familiar pang of self-hatred. Making a secret of his desires was not new to him – for 60 years he had kept his bisexuality a firmly guarded secret – but the tender age of his love interest was. “Love is to instruct, to show our beloved what we know of the sources of light, and this may be the declaration of a crafty and lecherous old man,” he later wrote. “I only hope not.”

But although things might have never got easier for Zimmer – a relapsed Mormon and now a married family man, Zimmer has only ever spoken of Cheever with a complicated mix of anger and great, resolutely fettered love – they did for Cheever. They were friends, Cheever told Max, that was all: friends who were occasionally more than friends; who, from time to time, talked about things that friends did not talk about; who called each other up to describe their own soft naked bodies, and to breathe heavy down the phone.

Sometimes Cheever took Max to parties, and the somewhat dazed young writer met luminaries like Saul Bellow while guiltily wondering if everyone knew what was going on between him and Cheever. And at other times, Cheever tried and failed to distance himself from Max.

Cheever was at a crossroads, and he knew it. He lingered there anxiously for as long as he could, hoping life would make the decision for him. He certainly could not do it himself; could not decide if he should finally embrace the image of the warm-smiling heterosexual family man that had never before sat well with him, or if he should throw it all away at 68 and become a single, swinging gay man, living by himself at an apartment in the city and taking lovers like Max.

But though he was tormented by indecision, Cheever could never stay away from Max for long. He wrote him letters; he called him up on the phone; he crawled, panting, across his body. “I love you,” he wrote in one note, with all the icy frailty of one of his own doomed, nobly misguided heroes, his narrow handwriting arcing across the page.

There are almost no metaphors in Cheever’s writing. Things are like other things, but that is as complicated as it gets. There is a neatness to a novel like

It is the same way in his correspondence, particularly those letters from the last few years of his life. Slowly dying in a hospital he hated, he jotted missives to friends, colleagues, his family. “I have been attacked by a nuisance of a cancer,” he wrote in one. “I am as bald as an egg. However I still get around and am mean to cats.”

He got to die at home at 4pm on June 18, 1982. A few days later, Max Zimmer was standing in his own apartment and banging his head desperately against a wall. He was, for the first time in what felt like a very long time, alone; without direction. His girlfriend had never known about Zimmer’s affair with Cheever – now, red-eyed and crying, he told her. He thought she’d leave him. Instead, she put an arm on his shoulder, and they got down to the business of living the rest of their lives.

Maybe there are no such things as happy endings. It is true they are rare in Cheever’s fiction. His stories end with embarrassed men lying face down in the dirt; with destitute couples forced to move on to the next town; with bleak-eyed children staring their fathers full in the face. And if Zimmer is ever going to be entirely at peace with Cheever and with what Cheever did to him, such peace has not settled over him yet.

Zimmer did not know Cheever’s family, had never met them, and so had no reason to suspect they would know about his relationship with the older man. Nor, when he turned up to Cheever’s funeral, nervous and hot in his smart suit, did he have any reason to suspect there’d be room up the front for him to sit. He was ready to hover somewhere near the back; to float about with the old work colleagues, and the mutual acquaintances, and the long-lost friends. So it was to his surprise when he walked into the church and there, at the end of the two crammed pews of Cheevers right near the front, was a little spot, saved just for him. And where there could have been scowls and downcast eyes, there was instead Cheever’s children, Benjamin and Susan, smiling up warmly at him.

So no. Maybe there are no such things as happy endings. But maybe instead there is something else; maybe there is the warm, uncomplicated glow that comes over us when, after so much time and so much hurt, things are finally just about okay.

Falconer, selected by Time Magazine as one of the hundred greatest novels of all time, is available here.