When Steve Wynn, the casino magnate, decided to sell “The Dream,” Picasso’s great, erotic portrait of his mistress Marie-Therese, he called his friend, the hedge-fund mogul, Steve Cohen. He knew Cohen coveted the painting, so the two men came to an arrangement. Cohen would pay Wynn $139 million – at that point the highest price ever paid for a painting – and the painting would be delivered to him.

Just days before the intended handover, Wynn was talking about the sale with some guests at his Las Vegas casino – among them Nora Ephron and Barbara Walters. While he was showing them the painting, Wynn – who suffers from an eye disease that distorts his peripheral vision – gestured with one arm and, in doing so, accidentally put his elbow through the canvas.

There was a brain-curdling ripping sound. Wynn leaned in for a look at what he had done: There was a two-inch tear in Marie-Therese’s left forearm.

The sale to Cohen was temporarily cancelled. At great expense, the painting was painstakingly restored. It was said to be so effective that not even an expert could see that anything untoward had taken place. Seven years later, the world had forgotten the fiasco, and the sale went ahead.

I remembered the story after seeing a show by Kader Attia, a French artist of Algerian origin, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. Attia’s recent work is all about injury and repair. He reminds us that, although in the west we are in thrall to the idea that restoration should return an injured thing to the pristine state it was in before the injury took place, other cultures in other times have treated injuries quite differently.

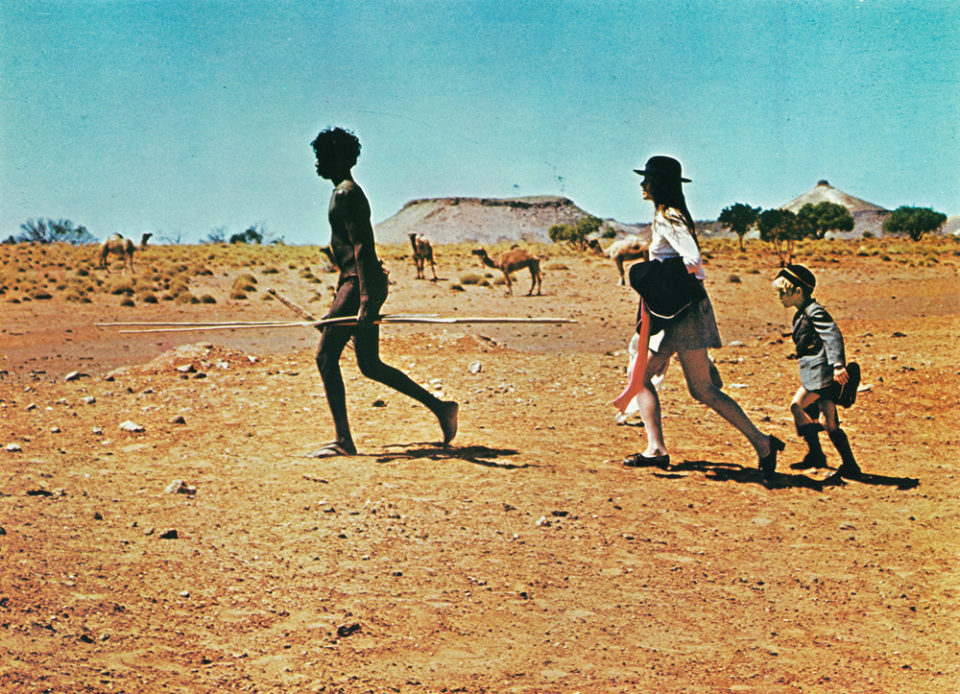

Kader Attia, Untitled (detail), 2014, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 2017. 116 stained glass fragments, metal screw hooks and fluorescent fixtures, image courtesy and © the artist, photograph: Jacquie Manning

I have seen broken Korean ceramics, for instance, painstakingly restored not with invisible putty or glue but with alloys of shining gold, so that every break was emphasized, the shattered work made into something new, the cracks imbuing it with greater nobility and aesthetic truth. It was as if injury were somehow a sign of prestige, and a necessary stage in a process of positive evolution. Religious rites, from circumcision to scarification, have taken a similar approach to the body.

Attia is plainly fascinated by all this. He applies his take on damage and repair to bodies, psyches, and whole cultures. Among his works at the MCA are a lute made from a French colonial army helmet; percussive instruments made from discarded plastic bottles; and an abstract arrangement of stained glass reconstituted from a shattered church window. In each case, the broken or traumatized thing is reconstituted, in ways that make no attempt to conceal the damage, but rather, highlight it.

Born in France but raised both in Paris and Algeria, Attia has a passionately moral take on the world. He was educated in Paris and Barcelona, worked in the 90s in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and has a studio in Berlin. He reveals in interviews both a poetic and philosophical bent. He is best known for several seemingly unrelated works in different media, each one a deftly compressed image that bursts like a firework into a whole set of cascading, interlinked meditations.

“Flying Rats,” which was shown at the Lyon Biennial in 2005, consisted of about two dozen life-size sculptures of children made from mashed-up birdseed. They were placed in a 150-square-feet cage with 150 pigeons for over two months, during which time the hungry pigeons slowly pecked away at the children.

Attia may have been driving, as I have read, at the idea that childhood innocence is elusive, a mirage. But the installation crackled with life, and was too disturbing, too combustible, to be limited to a single interpretation.

The same goes for “Oil and Sugar #2,” a short video which is one of the highlights of the MCA show. In the yard outside his studio in Paris, Attia built a solid box out of white sugar cubes. He then poured crude oil over the structure, which slowly turned black and then collapsed in an unforgettable image of slow-motion deliquescence.

What does it mean? You tell me. Sugar helped drive the slave trade and Europe’s rush to colonization. Oil plays a crucial role in 20th century power dynamics, overwhelming an earlier status quo. That might be one lens through which to see the work. Another would be to think of it in terms of religion, and specifically, Attia’s interest in the spiritual tension between presence and absence. The blackened cube might allude to the holy Ka’aba in Mecca. The black liquid could be seen as a spiritual force, transforming substance into nothingness, subsuming identity into an annihilating loss of self. Either way, as a poetic image, the work – so rudimentary in material and execution – is unassailable.

“Ghost,” an arresting installation in a neighbouring gallery, consists of several dozen life-sized figures made from aluminium foil. Lined up in rows, they appear to kneel and pray, like chador-wearing Muslims in a mosque. Attia has long been interested in spaces regarded as sacred by the followers of different religions. When filled with praying adherents these spaces brim over with spiritual presence. When prayer is over they seem, by contrast, emphatically empty. For Attia, these states of presence and absence are intertwined.

Those earlier works concerned with spirituality and community have been supplanted by Attia’s deepening interest in injury and repair. There is a link, he believes, between the Western idea of repair, obsessed as it is with erasing all evidence of the injury (as in Wynn’s Picasso, “The Dream”), and our current era of political amnesia.

It is vital, he insists, that we remember – perhaps even ritualize – injury and trauma, rather than conceal it or kid ourselves it never happened.

When French colonial powers took control of parts of Africa, they were appalled by traditional scarification practices, seeing them as barbaric. They banned them, failing to see that scarifications, as Attia argued in a recent essay on his website, “are the physical manifestations of the symbols that represent an individual’s immunity from psychological issues, and one’s safeguard from exile inside his own community.”

Where these African traditions celebrated injury as a stage in the evolution of the psyche and the community, the “modern era,” writes Attia, “through colonization, erased the past.” Its “dogma of disappearance” maintained that “the repaired injury must be devoid of any scars.”

Attia’s recent work is all about this dogma of disappearance, this amnesia. Recent traumas to the body-politic in France have everything to do, he believes, with a failure to get to grips with past trauma. The debate over illegal immigration, for instance, ignores not only the extended injury – an excruciating slow-motion tear – perpetrated by French colonization in North Africa, but the debt owed by France to the thousands of colonized people who fought and sacrificed for France during the two world wars.

In his slide show, “The Debt,” Attia juxtaposes images of the soldiers recruited in France’s African colonies with more recent images of the undocumented immigrants who are, in a sense, the grandsons and granddaughters of those soldiers. One image shows an undocumented immigrant demonstrating in front of Paris’s Palais de la Porte Doree, which was inaugurated in 1931 as a Museum of the Colonies. (Later, ironically, the same building became a museum of immigration.) He holds a sign saying: “Our ancestors died for France in 1914-18 and 1939-45. Did they have documentation?”

We evolve, believes Attia, only by admitting our injuries, keeping our scars visible. It is fruitless, for instance, trying to think through the present crisis of Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism without reckoning with the systematic, generations-old thwarting of hopes and dreams of young Islamic people, first through colonization and war, and then through economic and cultural marginalization.

Attia makes this point with a room-size installation called “Culture of Fear: An Invention of Evil.” On tall, prefabricated shelves, it sets 19th century illustrations of North African “barbarism” – public torture, brutally humiliating conquests, displays of the decapitated heads of Europeans on the gates outside Arabian cities – beside magazine covers and books addressing current fears: “ISIS: The State of Terror,” “Al-Qaeda: The True Story of Radical Islam,” and so on. (One typical magazine cover shows a woman in a black burkha about to cover Botticelli’s Venus with a cloth.) The work fails as art, but Attia’s salutary point is clear.

“The lack of direction given to today’s youth gives them little choice but to look to the Internet and social media to learn history,” he writes. “There, the injuries of the past are stigmatised through vindictive, xenophobic, and above all, violent discourses, from which the politic of fear coincides with the longing many adolescents feel to belong to a powerful and feared group.”

That longing, as we know all too well, too often ends in tragic self-sabotage, far more dire in its consequences than putting an elbow through a $149 million painting. Let the scar heal, Attia seems to be telling us, but let the scar tissue remain. Don’t let anyone deny the injury’s existence. And yet I came away from the MCA with the sense that, even as Attia’s intellectual range is widening and his political engagement deepening, his ability to find corresponding images and artistic forms is not keeping pace – as if the wounds he reveals and the tissue of artistic reflection can no longer be merged.

Kader Attia’s exhibition will be at the MCA in Sydney until July 30.