The red storm that threatened Sydney has passed, leaving only a tightness of breath, a fine veneer of dust over everything, and a vague taste of dirt on the tongue and in the back of your throat. Micro-particles swept off the drought-stricken surface of the Murray Darling Basin and carried citywards over the Blue Mountains by dry powerful winds; nature’s own dose of toxicity reminding us it is always there to be felt. All blown away for now, it seems, leaving us with a perfect Sunday afternoon, the kind of sunny day where nothing can go wrong.

I guess the internet is a little like that, the communication static like so much dust in our minds and hearts. There are illusions of intimacy when we get ‘social’ online, but the truth is we don’t get close till we meet. Suddenly there’s a reminder in a backyard party that we’re still a part of a community and its history. You breathe a little better that night when you go to sleep.

Samantha and I walk in and Robert Forster has already begun. It’s only 4.30pm and as expected I’ve struggled to get here, sorting my kids out till I can return in a few hours’ time and make dinner. We stand at the back, in the entrance to the kitchen, leaning against wooden cupboards. Forster is neatly framed by a large doorway opening out into a rectangular yard, a grey sheet and a blue-and-red sheet hung from a clothes line behind him to give off the mood of a makeshift stage, something akin to Forster playing from the back of a circus or rodeo truck.

Artwork: Robert Forster, The Best of the Solo Recordings.

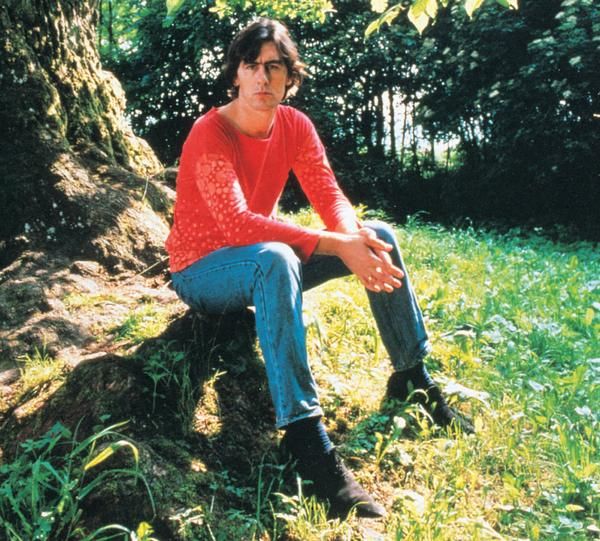

As one of The Go-Betweens’ principal songwriters and one of the country’s finest music critics, Forster is something of an icon in the landscape. Tall, effete, strangely wide-eyed – as if something humorous has happened that we can’t quite see – Forster writes similarly strange, effete, wide-eyed songs about loneliness and life, celebrating it with ease in songs like ‘Spring Rain’ or darkening his lens in ‘The Clarke Sisters’, one of his many portraits of female struggle and empathy that make him rather unique as a male songwriter in this country.

Samantha bumps into an old friend she used to share a house with in Surry Hills thirty years ago. Samantha’s mother has died only a few weeks back and the friend is one of the very few people in Sydney who met and knew her; a crossed wire of fate that allows for a little commiseration today. I meanwhile look down and see Shelley sitting on a lounge, laughing. Our kids used to play together when I lived out at Millthorpe, working on my first book. She takes a selfie of us and sends it to Frannie in Millthorpe, beautiful Frannie who lost her brother so painfully to drugs decades ago, and in whose garden I’d lived, making coffee on a pot-bellied stove and watching country mists envelope it in winter, the trees all spare as bones.

Already it is clear the afternoon will be one of acquaintances and surprises, of old familiar faces coming back into view. Its takes at least one song before Samantha and I can focus on what Robert Forster is doing. Hear him inside ourselves rather than just with our ears. That settling of self into the sound; or the sound settling into you.

The first song that makes an impression is an amusing one, ‘I Love Myself (And I Always Have)’. Forster preambles it by saying it’s one some people really relate to. There’s a great line in the song about how, “I look into the mirror – and I smile.” It’s a very Forster type of trick, the second half of the line dropping in after a marked pause. It’s funny, like a punchline left hanging in space. As if the pause itself might be the joke. There’s a sly, paradoxical element of encouragement in it. You can love yourself, if you so wish.

After it’s over, someone calls out and asks who the song is about. “You know what,” Forster says, “I will tell you.” Everyone’s waiting for the big reveal, but Forster tells this foolish story of sending himself an email to test if his messages were working, writing himself a note, “Hello Robert, how are you? I’m feeling really good…” Days later his wife happened to open the message and remarked to him, “You really like yourself, don’t you?” Forster reckons it was an easy jump to the lyric and title for his song.

Soon enough, he plays ‘Darlinghurst Nights’ with its memorable opening line, “I opened up the notebook and out jumped some tears.” Darlinghurst 1986 he says, a time and place I know well too. Nostalgia and sorrow and something alive get all mixed up in the song; the afternoon sunlight is a deep hot yellow, passing little diamonds over Forster through the shaking leaves of a backyard tree that gives him even more precious shade. The synchronicity of natural light and shadow is a neat light show for the song itself.

Forster lifts the mood with ‘Spring Rain’. ‘Surfing Magazines’ is a hushed singalong, a call to a teenage coast. Later Forster puts his hands over his eyes to pretend he is going backstage while we clap for more. He ‘returns’ with an exquisite reading of ‘Dive for Your Memory’ that is enough to make you weep. The story of a lover saying they had no chance; and his invocation in return, “We stood that chance.” It makes me think of the old John Cassavetes wisdom from the film Love Streams… love never dies, it only changes form, from love to hate to regret to friendship to memory. Real love remains in what you are; having defined you, it’s not something that can be erased. One feels the ghost of Forster’s old song-writing partner from The Go-Betweens, Grant McLennan, emerging somehow in all this.

Robert Forster in a Summer Hill backyard. 25/11/18. Photography by Christine Harris-Smyth.

Forster ends with ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Friend’. Again, it is from a woman’s perspective, the lover of a rock ‘n’ roll journeyman who seems to be sliding down in his career more than he is rising upwards. Yet another performer lost in music: “You’re home late and you smell of music. All my patience, all my love, that’s now all at stake.”

When the song ends, Forster is greeted by deep applause. It’s been a set of rapture and regret, with those typical flashes of flamboyance and humour that make him so original. Forster’s literary qualities and near-awkward, yet catchy guitar work (when Forster plays a lead he concentrates like a 12-year-old learning his first chords) opens itself to his influences: the Velvet Underground, The Only Ones, the Modern Lovers, Dylan… but there’s a formality with his humour that could just as easily make him the Jane Austen of Oz Rock, as well as a dreaming freeness that suggests a touch of Jack Kerouac’s romanticism is in his blood too.

It’s so easy to take people who have been around a long while for granted. Australia can be especially cruel in this regard. Watching Forster exert his magic I am reminded of those icons I have grown up with, most especially during that era in the late 70s and 1980s when certain songwriters and performers became part of how we lived and marked out some freedom or imagining for us… Forster and McLennan, Kuepper and Bailey, Nick Cave and Rowland S Howard and Mick Harvey, Rob Younger and Deniz Tek, Paul Kelly… there are many others, of course, but for someone like me these figures were like imaginary older brothers who reported back on a world I might somehow be a part of too.

Backyard concerts like these come from websites like Parlour, where artists can make a deeper connection with fans – and where fans can create small community events that connect people to a beautiful moment like today. Inevitably in this crowd of about 80 or so people everyone knows one another – or someone that has known you. An artist called Peter says hello to me, hands me a sticker of a coffee cup with two polar bears sitting inside (I don’t know why, but I like it). Another artist friend called John talks to me about poetry and how he is making stop-motion films for what he is writing. He says he heard once that Morrissey had said Robert Forster had been an influence on him, something that makes a lot of sense given The Go-Between and The Smiths were both with the UK label Rough Trade.

Forster remembers me from past interviews we have done and comes up to say hello. I tell him how ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Friend’ gave me this funny feeling inside – and make a stabbing motion to my heart. “Good,” he says, “that funny feeling is what I am going for.”

The journalist Rick Feneley approaches us and we all talk about the beauty of the afternoon and the warm sense of the crowd. I’m reminded of Rick’s early first book Sly, the story of a boy growing up on the south coast of New South Wales and how much it reminded me of my growing up too. Standing with Robert and Rick there’s this faint feeling of shared boyhood that is hard to put a finger on. Maybe that is what this is all about… uncovering or recovering ourselves again and again.

Robert has other people to speak with, but he tells me he saw Dave Graney and Clare Moore play in Brisbane recently and how great they were. That I really must see them. He loved catching up with them after and finding out about old Melbourne friends. “Dave and Clare – they always bring the good news.”

It’s only just past six when Samantha and I leave. I almost forget to say goodbye to Christine who organised the event with her partner John. His previous partner of nearly three decades died a few years ago and his 50th was riven with grief. Christine had decided with John to make a happy birthday occasion for him this year, a kind of belated new dawn. “John is the love of my life,” she says. The passion is so Christine. She had messaged me at the last moment to see if I’d like to drop by on the day. With the paper I was working for having gone into hiatus, and Christmas coming up, I admitted it was probably not something I could afford – but Christine told me to come anyway and we’d just work it out – and that funny old feeling of knowing people and past lives and kindness came back to me, as it so often does. Always this kindness and generosity from people that I feel I only half know, yet am somehow bonded with across the days and nights of my inner city life.

Samantha and I hold hands walking up the street. I will drop her home and return to my children to make them dinner. And the afternoon will stay with me like the sunlight through the trees of the backyard, little bits of memory and diamonds of connection with all my rock ‘n’ roll friends.

Mark Mordue, Robert Forster and Rick Feneley in Summer Hill. 25/11/18. Photography by Samantha Hutchison.