“The way they lied, those days have to be over.” It’s clear that Steven Spielberg intends the words of Tom Hanks to ring out from the 1971 newspaper setting of his latest film, The Post, to today’s fraught political landscape.

The parallels are blue-sky clear: as a historical story of governmental lies and persistent journalistic integrity, the film is a moral parable for the present day. But a murkier political reality lurks just below Spielberg’s intentions.

A dramatisation of the Pentagon Papers scandal, The Post sees Spielberg developing the preferred mode of his later era – talky, smart blockbusters for grown-ups, washed with uneasy American idealism and glossed with patriotism.

Those who discount Spielberg as the dad of multiplex moviegoing do so at their own hazard. Sure, he may be the world’s highest grossing director at the global box office, but this isn’t empty populism, rather, its popular cinema at its prime.

Well, not quite. Just two years ago, Bridge of Spies marked Spielberg’s pinnacle of intelligent mass entertainment. After the dialogue-driven Lincoln (2012), yet another excursion into US political history, Bridge of Spies was an action-inflected tale in the dead of the Cold War, with Hanks playing another idealist working to save his country – and a KGB agent – from the Red-menace mania. From its first to its final frames, it was taut and thrilling and morally alert.

As a neat companion piece to Bridge of Spies, The Post keeps Spielberg far outside the blockbuster cycle of his early days – the pure genre works of Indiana Jones, of Jaws and Jurassic Park and E.T. the Extra Terrestrial and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Those films were all stories of childhood heroes, boyhood dreams and family cohesion. The Post retains their commercial sensibility – particularly in the opening sequence in the thick of the Vietnamese jungle designed to acknowledge the sacrifices of American soldiers – relaxing the relentless action beats for a genre-tinted, office-set journalism drama of heroes and villains.

Here, Spielberg’s heroes are whistleblowers and soldiers, journalists and publishers, most prominently, Kay Graham, owner-publisher of the Washington Post. The villain, a silhouetted Richard Nixon, haunts the film’s final sequence in an uncharacteristically (for Spielberg) pessimistic epilogue.

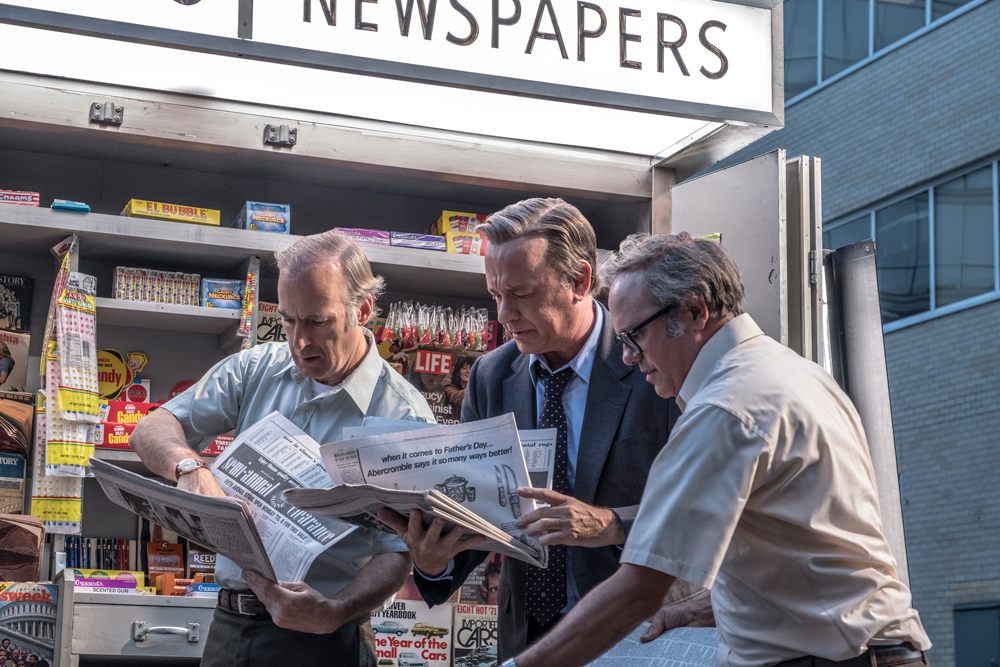

Tom Hanks (Ben Bradlee), David Cross (Howard Simons), John Rue (Gene Patterson), Bob Odenkirk (Ben Bagdikian), Jessie Mueller (Judith Martin), and Philip Casnoff (Chalmers Roberts). Photo Credit: Niko Tavernise.

Patronised as a “little local paper” and tainted by its reputation for cosily serving governmental interests, the Post was steadily transformed by Katherine ‘Kay’ Graham into an organ of national prominence and investigative reporting across the 1960s. Graham had stepped into the role after the suicide of her husband, Philip Graham. By 1971 both she and her “cash-poor” paper were ready for a very different challenge.

Played by Meryl Streep with a patrician north-east accent and doubtful eyes, Graham was confronted with a steep choice: whether to publish reports on a set of Vietnam War taskforce papers from the Department of Defense. Leaked by former military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, the papers marked a grave security breach, comprising highly classified revelations that the US knew it couldn’t win the war as early as 1965 and had contravened the Geneva Convention.

Spielberg’s favoured moral-compass protagonist, Tom Hanks, is Ben Bradlee, The Washington Post’s legendary editor. In a recent interview Hanks himself described the Pentagon Papers not so much as a single bombshell, but “a collective weight of ongoing knowledge or testimony that the Vietnam War was unwinnable.” Beyond that, they revealed three decades of US prying and planning before the war, including an effort in 1954 to obstruct Vietnamese elections.

The slow zoom of the light on the photocopier, beaming across Ellsberg’s face in grotesque close-up and burning up the room as he copies reams of shadowy documents, tells us this is a treasonable action. The New York Times comes to publish the very first set of leaks, only to be censored by a federal court injunction initiated by the Nixon administration. It was the first time a newspaper had been banned from publishing in the United States’ history.

Matthew Rhys portrays Daniel Ellsberg as a conscience-charged isolate after what he has seen in Vietnam and then in the duplicitous company of Secretary of Defence, Robert McNamara. Ellsberg can’t surrender to lies. He insists that “if the public ever saw these papers they’d turn against the war,” asking Post journalist Ben Bagdikian (TV comic Bob Odenkirk), “Wouldn’t you go to prison to stop this war?”

The question goes from abstract to concrete quickly, as the Nixon government argues that publication of the rest of the papers would violate the espionage act. A cowardly Post board member warns that, should it publish the leaks, “The Washington Post will cease to exist.”

Hanks’ Bradlee is unswerving: “If the government tells us what we can and can’t publish, then the Washington Post has already ceased to exist.” In scenes like this, Spielberg’s own outrage is palpable. As usual, Hanks personifies the liberal American conscience, his heroic morality underlined by staunch nationalism.

That’s where the film’s most fascinating and most contradictory element comes into play. It’s easy enough to spot the contemporary comparisons that Spielberg is nudging us toward – the ruptures in the journalism industry today, the transition from print to digital, the fake news, the way that leaks and whistleblowing, from Julian Assange to Chelsea Manning, have become a standard disruption of the news cycle, the intrusion of social media in pushing a twenty-four-seven windstorm. All of these things have normalised the now unending stream of US Presidential scandal.

‘The Post’ mainly comprises scenes in which people talk to each other in offices and smokey dining rooms – but Spielberg makes these indoor sequences dynamic, film noirish, anxiously paranoid. Photo Credit: Niko Tavernise.

The Pentagon Papers were pre-Watergate, and in a neat postscript, Spielberg finishes with the raid of the Democratic National Committee offices, showing how Ellsberg’s whistleblowing and Graham’s bravery as a publisher coincided with a new era of governmental creeping. Many critics have commented on these parallels – and kudos to Spielberg that he knows that the political context of now creates those resemblances, without dogmatically spelling them out.

But the more interesting thing is Spielberg’s blindspot. As a liberal American filmmaker, he sees these kinds of intrusions as anti-patriotic exceptions rather than the tendency of how the US governs – dishonestly, creepily, self-servingly. The Post positions government reactions to the Pentagon Papers and Watergate as instances of anti-Americanism. But much of the world sees it as the very definition of American leadership and operation – as part of a pattern of lying, covering up, meddling and moving on. That paradox is at the weird, ultra-American heart of The Post.

The narrowness of the film’s thesis – that the Vietnam War should not have been fought because it was unwinnable, not because it was essentially wrong to defy another country’s self-determination and slaughter its people through violent invasion – is similarly odd and myopic.

The general air of triumphalism, that sense that, in the US, democracy inevitably wins out – one character refers to the US unironically as “the Republic” – isn’t the only aspect of the film that rings a little false. At his worst, Spielberg is a sentimental filmmaker, unable to direct moments of emotion with nuance. He has publicly discussed his Aspergers diagnosis, and there is something of the outsider and the mimic in the unmodulated way he renders emotional scenes – as Graham’s relief turns to joy, John Williams’ piano and strings tinkle mushily.

Still, it’s to his credit that Spielberg fleshes out what the revelations of these papers meant for the US at the time. So often in these sorts of thriller-ish dramas, the trigger for the action is a red herring. But Spielberg skillfully interlaces archival footage to animate the Pentagon Papers’ evidence that a cascade of political leaders – Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy (“The United States, as everyone knows, will not start a war”) and Lyndon Baines Johnson – had been lying about Vietnam to the public and congress for thirty years and still sent American boys into a pointlessly perilous situation, just to avoid humiliation. (Australia’s own Prime Minister, Harold Holt, committed us deeper into the Vietnam War with his affirmation, “all the way with LBJ”.)

As a journalism-meets-spy film, The Post mainly comprises scenes in which people talk to each other in offices and smokey dining rooms. But these indoor sequences are made dynamic with handheld cameras and shots that track us across the horizontal grid of newsroom fluorescent lights (familiar to us from that other titan of the journalism film, All The President’s Men), and upward from floor to ceiling. There are film noir-ish scenes of paranoia, in which the camera circles a gloriously kaftanned Streep from above while she’s on the phone, trapped in indecision during the film’s middle sequences, as well as shots of diagonally-cut architecture reminiscent of one of the great films of 1970s political anxiety, The Parallax View.

Other moments of abstraction leap out from the blue-tinted office backdrop: on a New York street corner, when Bradlee and his staff seize on the first, fateful Pentagon Papers leak published in the Times, the camera lingers as the wind whips their hair and ties into the blustering air, and they grasp the newspapers thrown into shock. These rich visions of metaphorical, political chaos were all but absent from the last big journalism film, Spotlight (2015), also scripted by The Post’s Liz Hannah and Josh Singer, but less imaginatively directed.

Rich visions of metaphorical, political chaos. Photo Credit: Niko Tavernise.

For her part, Streep embodies Graham as a torn, under-confident woman, anxious but eventually resolute. “She felt alone in that decision” to publish, said Streep recently. There’s a gender critique here that’s very of-the-moment, and not typically Spielbergian – as a woman in a man’s world, Graham is spoken over, coddled, undermined (she has her seat pushed in for her by a colleague at a business meeting, is pushed past by a board member) but she comes to model a different kind of leadership – collaborative, considered, enquiring, open to feedback and changing course.

The Post is a film that’s deeply nostalgic for print. It speaks from one moment of rupture in the media industry, to another moment today. Freedom of the press versus governmental secrecy – whether the press serves the governed or the government – is its core moral story.

Hanks spoke recently about how he first read the script in October 2016, a time when he thought the next president would be woman. That unerring faith in US politics as following a self-correcting, ever-progressive trajectory is at the centre of The Post’s belief system. That the film failed to realise that a new US president could initiate his own ongoing siege on the free and independent press, that it was made in one era and released in another, is both the biggest failing of its liberal Hollywood politics, and its most intriguing facet.