Every typewriter has its provenance, its own fingerprint – the crooked key that leads detectives to the blackmailer. My friend, the writer Elizabeth Harrower, who still types her letters, told me that she and Patrick White had a typewriter mechanic they used regularly, in North Sydney. It was like getting your piano tuned.

Cormac McCarthy’s battered Olivetti typewriter was considered so talismanic that, in 2009, it sold for $254,500, at a charity auction, after which a friend replaced it for him with the same model, bought for less than $20.

As a teenager I found a grey portable on which I attempted to teach myself ‘touch typing’ from an instructional booklet, doing the exercises, ASDFGF etc. I never really succeeded. The eyes kept looking at the fingers.

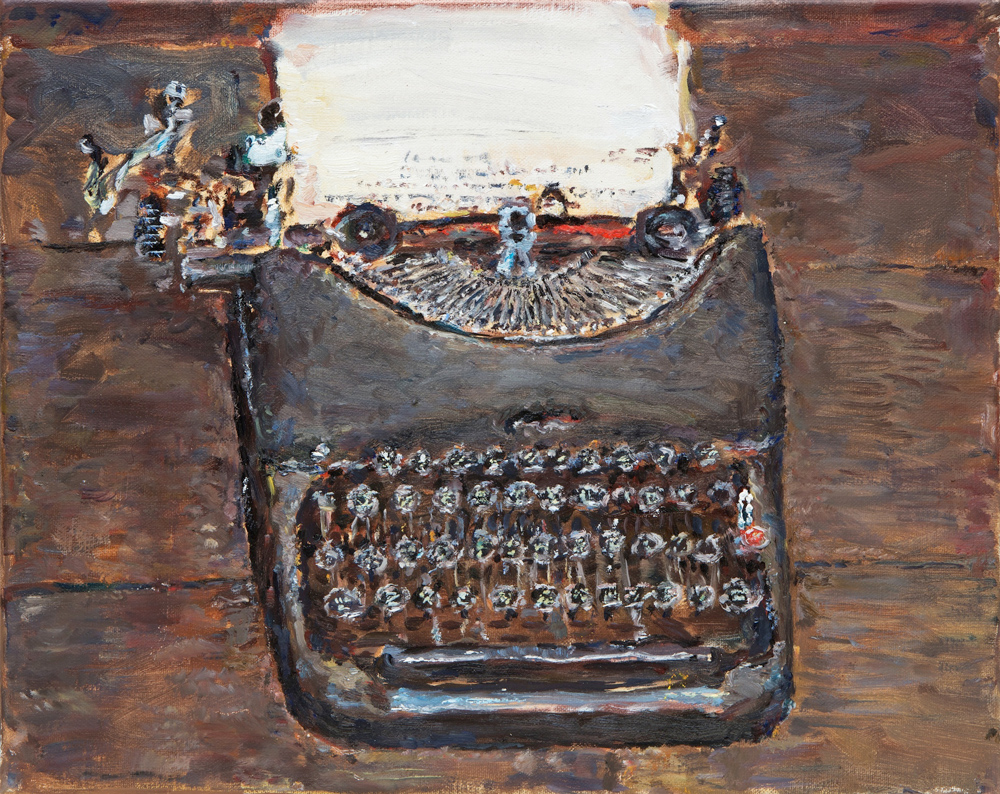

My remaining typewriter is a large office model Remington, bought in 1982 from a secondhand office supplies shop near Central Station. I nearly broke my arms carrying it home on the train. The Remington was a step up from my tinny portable with awry keys; a V8 of a machine with a lovely action. I wrote my first book Days & Nights in Africa on it, in many drafts. In following decades, since the advent of word processing, this hefty machine has languished beneath my desk. I use it now and then to weigh things down, glueing primed linen to plywood boards.

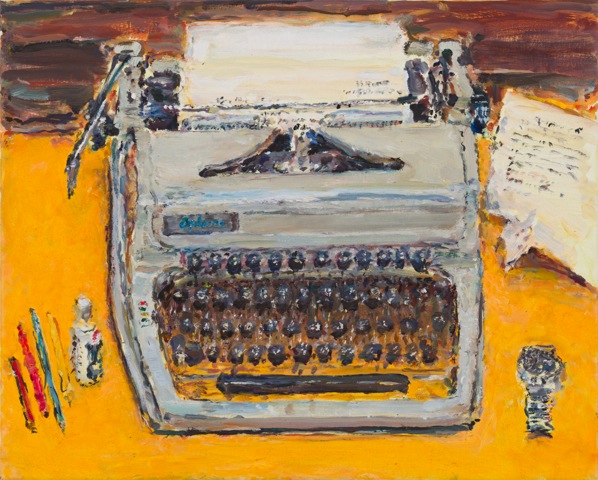

Last year I felt like typing a letter and brought it up to the kitchen table, to show my son Felix how things used to be done. It revived an old memory, the way it clarified my thoughts, the physicality of pounding the keys. Felix reckoned it was very ‘steampunk’. After that, I lugged it downstairs, placed it on some old dark floorboards, removed from a hatch near our letterbox, and started a painting. My partner Jan nearly broke her ankle when I forgot to put the boards back. A month later, I borrowed my friend Alex’s Olivetti Lettera, the same model as McCarthy’s, and then a Remington portable that I saw in the Grand Days shop on William Street. A friend Fiona lent me her 1970s beige Optima, next to which I placed my father-in-law’s watch. I painted them all.

I came late to still life painting, waiting until I was sixty, three years ago. I had tried at times before that, but was never happy with the results, and so I stuck with painting landscapes and portraits, which I enjoyed so much. Then one day I saw a Velasquez painting in an old masters exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW and noticed some beautifully painted red onions in one corner. On the way home I went to Harris Farm and chose two red onions with the hairiest white roots, took them home and did a painting on the concrete outside.

One day Jan came home and saw me downstairs sitting on a fold-up stool in the lightwell of our terrace house, painting some dirty potatoes. She called out, “Shouldn’t you wait until you’re too decrepit to leave the house before you start doing still lifes?”

For more than half my life I’ve lived in the same part of Sydney, for most of that time with Jan and our children, in a house on Womerah Lane, Darlinghurst. From this address I’ve gone out on many journeys to paint. I work always from life, in oils, gouache or watercolours, on a small, portable, scale. Over that time, I’ve found my range of subjects gradually becoming more local. I take increasing pleasure in exploring things close to home: walking down to Rushcutters Bay Park with my backpack of oils, or to the ledge of grass at McKell Park, for that long view north up the harbour, exploring the back lanes of Kings Cross. The buying of fruit and vegetables is one of the daily routines that I’ve decided to make paintings about.

In the spring of 2016, our daughter Matilda finished school and came home to study for her HSC. I stayed home too, and began a new series of still lifes. The idea was to create an atmosphere of industry and also to keep her company. I’d sit down in the lightwell of our terrace house painting cut pumpkin while, upstairs, she’d be reading about Stalin’s purges and methods of resuscitation. We’d meet up for lunch, sometimes eating the fruit or vegetable I’d just finished painting.

Jan would come in from work and suggest things to me, bringing tamarillos one day from the shop, and, a few weeks later, asking the question: “What about eggs?”

How could I have overlooked them?

I ended up doing seven paintings of eggs, in different lights with different eggs, including my neighbour’s ones, from hens who had eaten our kitchen scraps.

I said to Jan that you can’t really paint eggs in an expressionist way; they require care. One morning I forgot a medical appointment in Bondi Junction, so exclusive was my concentration on the pale browns of the two eggs sitting in front of me. By way of inadequate apology I sent a postcard, made from a photo of the finished painting, and titled it, the missed appointment.

Tom Carment’s exhibition, ‘New paintings – old habits’ runs from 7 November until 2 December 2107 at King Street Gallery on William, 177 William Street, Darlinghurst: www.kingstreetgallery.com.au

Tom’s website: www.tomcarment.com