Tim Etchells and Barry Keldoulis should host their own reality television show. At the media preview for Sydney Contemporary they’re so smooth and sharp, so casually and reassuringly eloquent, we might be nervy contestants being put at ease before being forced to engage with the tests and trials of their latest episode.

In many respects, this is pretty much the truth – Sydney Contemporary is a bull run, a show and a half, and easily the country’s premier art fair, with 90 participating galleries, around a quarter of them international. The works of some 500 artists are on display, quite a few of whom are present to charm and explain. A program of talks and performances adds to the thrum across seven large bays (once upon a time these were galvanic working sheds where trains were built and repaired), with additional streams like Installation Contemporary, Paper Contemporary, Performeance Contemporary and Video Contemporary.

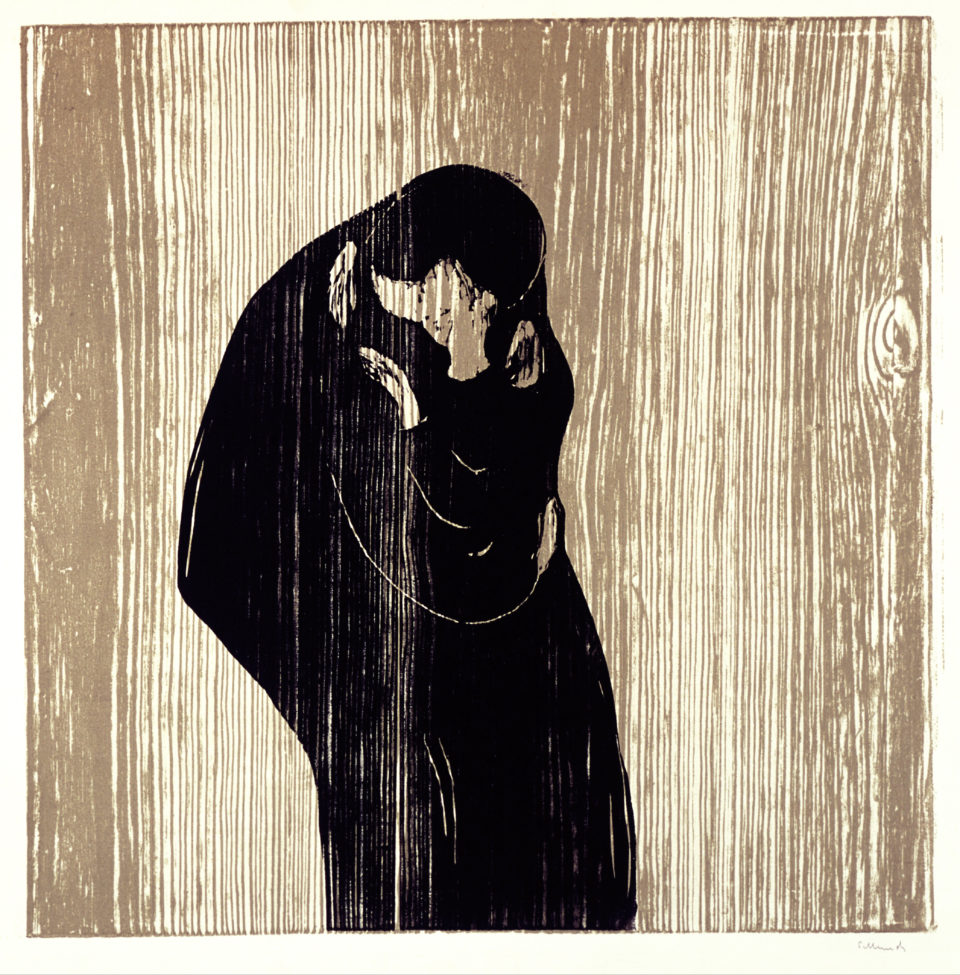

Mehwish Iqbal, Dichotomy of Foreign Seeds, 2017. Silkscreen collograph etching. Image courtesy of M Contemporary.

All of this offers a surprisingly thrilling and overwhelming vision of where art is right now – not from the strained thematic platform of a single curator-come-theorist, but from the gallery-driven commerce of what’s happening, hot and selling right across the world.

Here a hundred flowers blossom – from the earth of dirty lucre, the yen for attention, the Molotov of protest, the hunger for spiritual succour, and, yes, even a twisted sense of humour.

At the media preview, Etchells, the founder and owner of Sydney Contemporary, wears a simple black suit and white shirt. He is casually crisp, hair vaguely dishevelled, with an English accent that implies days treading the boards doing student Shakespeare. The hound-dog face and commanding air feed into a wearily alert presence that ultimately sets you in mind of Deadwood’s Ian McShane. Beware, and be charmed.

Keldoulis, the fair’s Art Director, opts for a silver suit, his shirt almost sharkskin patterned via some Balinese silk, everything about him – including his bald pate and Mandrake beard – exuding sharp-edged bonhomie and a magically easy, if potentially fierce intelligence.

What point the pop-psychology style guide to these two powerhouses behind Sydney Contemporary 2017, Mach 2017? Perhaps just to emphasize that a lot more than art is on display – and sale – here at the fair today. This place is a total state of mind and being; a circus tent of egos and personalities, not least those who come to look not so much at the art, but at each other. Everything here is up for display one way or another.

As Keldoulis takes over the business of swanning the media through the vast hive of booth-style mini-galleries that have established themselves inside the cavernous and undeniably beautiful Carriageworks (it too brings architectural ‘game’ to the event), it becomes even clearer the plethora of visiting curators are living artworks themselves: suave dynamos, aesthetic eccentrics and corporate reflections of the artists they represent, with each booth a distinctly flavoured rabbit hole into a locale, a consciousness, a voice for dissent, weirdness, sorrow – come into this room, see a red-corded web come performance art chamber that meditates on the nature of S&M; over there, a wounded forest, spectacularly photographed, panoramas of damage with creeks of laid ribbons the colour of blood; look closely on that wall, a rat’s skull, the size of your fingernail, hand-carved out of wood and hung from a pin.

Glen Hayward, ‘Fifty cent vs. Counter Fate’, 2014. Image courtesy of Paul Nache Gallery.

Power and money bubble through everything with a frisson of wildness, checked only by civilizing avarice. This is quite some place to be. Frankly, it makes most major art festivals look tired by comparison, and for all the grumbles about a commerce-first combustion engine you can’t deny the motor running behind this bright and powerful show.

In their warm-up act Etchells and Keldoulis deflect critiques that might imply art is pure and money dirty – and that when the twain meet only the crassest and shallowest float to the surface, insulting anything better or deeper. Like confused analyses of modern politics, this Puritan idea seems so anachronistic or simplistic it’s absurd. Ladies and Gentlemen, roll, roll up, welcome to the paradox of being alive and complicit today.

Etchells identifies “the pyramid” that Sydney Contemporary appeals to. At the higher end are the collectors; in the middle are “the occasional buyers”; and, taking care to avoid any degrading top-to-bottom typology, at least so far as the media are concerned, “in the third section are the general public”.

He explains the big ‘news’ that moving to being an annual – rather than bi-annual – event was a matter of “continuity” the galleries pushed for. When Etchells started Sydney Contemporary back in 2013, he took “a softly, softly approach”, not wishing to “overcook the market”. Now, it was clear “the time is right, the market is right, the business is here” to push Sydney Contemporary annually. The press release tells the story: 2013 and 2015 attracted 60,000 visitors and netted AUD$24 million in sales. The forward plans are exponential, not steady as you go.

Etchells sees the event resonating out in a vision for the whole city, with tourism and satellite fairs and exhibitions affecting restaurants, hotels and other businesses, adding “lustre to the cluster” that is Sydney Contemporary, the hub for what he sees becoming “a Sydney Art Week”. There is something actual to that potential energy as Etchell enthuses on a perfect day about “early spring here, when the weather in Sydney is really stunning”. His sense of timing feels very right. Let it come down – in crisp Sydney sunlight.

Keldoulis picks up on this momentum and states that “the fair is big and bold and exciting” – somewhere we hear that unsaid word ‘brash’ like a secret rhyme – but “keep in the back of your mind it’s really about the artists”. Despite prizes and government grants, the fact is, he says, “most artists survive through selling their artwork.”

Hayden Fowler, ‘Together Again’, Performance Contemporary, Sydney Contemporary, 2017. Image credit Jacquie Manning.

A bigger and better Sydney Contemporary also opens up international connections for curators and artists with other fairs. It’s a link not hindered by Etchells’s founding role with Art HK (Hong Kong), and his more recent activity launching Art13 London. Galleries from as far afield as Iran and Argentina, not to mention nationally and across Asia are present here in Sydney. The game is not just sales; it’s networking an art market internationally.

Keldoulis once worked at Luna Park as supervisor and he calls to the curators like the head carny as the main show tent is being pitched. The Chileans, he points out, “are drinking beer at 11am!” Over there a man is wearing AR goggles, trapped in a cage with a dingo jawing bloody meat. When I ask the Iranians why they are here they say a few polite things about Sydney, then they just laugh inexplicably: “That Barry is quite a force.” Elsewhere we stop, and for a moment are hypnotised by a vast, beautiful video work of a great flower that seems to be spawning – “it’s not a video work, it’s an algorithm…”

Keldoulis recalls the days when art fairs were basically stock shows that were hung floor to ceiling. No aesthetics to the presentation; no curatorial restraint or sense of audience; it’s a veritable picture of past garage-sale disorder and cash grabbing. He laughs at the crassness of it all: “I remember being with an artist horrified his babies were being presented ‘in this meat market!’”

Sydney Contemporary, like most international art fairs, has advanced a long way from those bad old days. It’s booths and walkways have been mapped by an architect, while Carriageworks, by Etchell’s own accounting, “is easily, easily, the best venue for an art fair in the world”. One of the most interesting aspects to the shaping of Sydney Contemporary this year has been the overarching request – mostly adhered to – for galleries to focus on only one or two artists, helping to create what Keldoulis calls “a much more elegant looking fair”.

The end result of all this: “Artists are now thrilled to be shown in art fairs,” Keldoulis says. “Tens of thousands of people, as opposed to maybe a few hundred [at a gallery], see their work.”

What we witness here is a juggernaut, a good half of it marvellous and breathing fresh from studios, unleashed from institutional imperiums and ideological visions that are normally the only avenue through which we can engage with so much new art on such a grand and immediate scale.

At the opening night this world of fascination threatens to tilt into mob narcissism as the peacocks of the bourgeois parade the aisles. Money and sex swim together and it’s hard to know whether to be seduced or repulsed. There’s something naked to it all, nonetheless, something real in the continuously charged exchange between art and commerce, the ‘market’ that makes Etchell and Keldoulis’ Sydney Contemporary what it is.

You will be hard pressed to see a better exhibition in this town for quite some time, the artworks rearing up at their audience, and even at their ring masters, like circus animals, freaks, clowns and strange entertainers caught in the spotlight of what, for now, is the proverbial greatest show on earth.

Sydney Contemporary, 7-10th September, at Carriageworks, 245 Wilson Street, Eveleigh, Phone (02) 8571 9099. Details here.