“Due to the Tohoku-Taiheiyou-Oki Earthquake which occurred on March 11th 2011, TEPCO’s facilities including our nuclear power stations have been severely damaged. We deeply apologize for the anxiety and inconvenience caused.” – TEPCO media release, 11 March 2011

Anxiety kills off hope. It is a condition that draws a large circle around the self and poisons everything within it. The sense of terror endemic to anxiety is the same fight-or-flight pang that creeps up on the unsuspecting consciousness when confronted with danger or the possibility of death.

But anxiety, the undead mind wandering aimlessly, lives on.

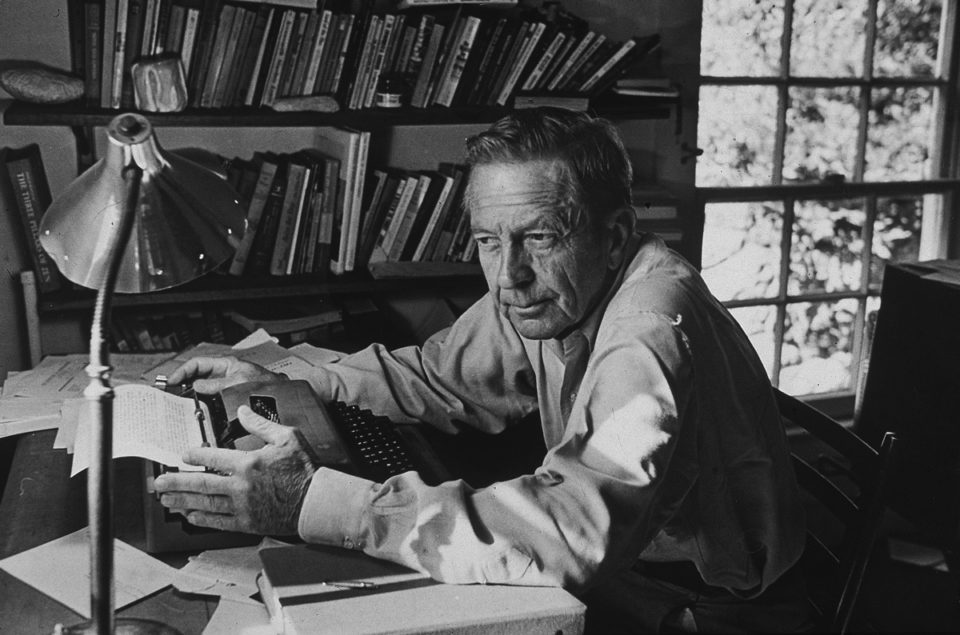

You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on is Sam Doctor’s latest photography and video show at Sydney’s Chalk Horse gallery and it is a tangle of anxieties. The title comes from the final line of the Samuel Beckett novel, The Unnameable, a monologic leap into to the predicament of the “You” and the “I” – of life among other people.

Its focus is the nuclear exclusion zone, Fukushima, Japan.

“There’s a big sign at the train station that says Fukushima: Nuclear Town,” Sam recalls, “It looked like a horror film. All the bikes chained up and the big station clock falling off. They were so proud of being nuclear.”

Doctor has a preoccupation with the aftermath of physical destruction. And equally its psychological counterpart, the places where disturbed nature and disturbed mind are left to reconcile.

He’s been here before, in anxiety-land: at a sulphur mine in East Java, Southern Indonesia (A Song for the Stonebreakers, 2011) then at a soil quarry near Chang Mai, Thailand (The Return, 2016). His project is to document and then interpret the succumbing of terrain to humankind’s long-established rapine tendencies, and what happens next. “I always walk a fine line between terror and beauty,” he says.

True to his word, in August 2017 Doctor scammed his way through the highly policed 20-kilometre exclusion zone around the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (another hope-killing radius) with a Japanese journalist, “KT”, and her former logger father, posing as his daughter’s fiancé. They showed Sam the family home, a ruin left in the same state as after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, now overgrown and wracked by the trauma of radioactive half-life. Every now and again they come here to say a logarithmic sayōnara to their old selves.

Doctor recalls the father’s grief-stricken tale: “He said it’s not like a tragedy where something terrible happens and you just have to get over it. He said he doesn’t know if his homeland will ever be fixed.

“It’s like when parents have a missing child and they keep the bedroom in the same way,” says Doctor, “That’s what their houses are like.”

There is something in the anti-natural power of a nuclear event that puts the ordinary human response to disaster out of step. “For the last five years the government has just been bagging up the soil,” Doctor tells me, “but the soil’s not going anywhere because it’s contaminated. So there are football fields of hundreds of thousands of these gigantic bags of contaminated soil just sitting there.”

There’s nothing to be done here but wait, fiddle, visit and reflect some. Fitting, then, that Sam Doctor’s three two-metre photographs, accompanied by a short video work, all depict a world in a state of ponderous pause.

Title: ‘Contemplation’, 2018. Details: Pigment print on cotton rag 120 x 180cm. Image courtesy Sam Doctor.

The most striking image is of a stygian mist rising into grey firmament, layers of dense green foliage wilding beneath it (a geothermal area known as “Hell”). In another, a figure in a HAZMAT suit ironically investigates a concrete ledge above an artificial lake, tool belt adorned as if there to measure or mend. In the third image, the figure, again in official exclusion zone livery, stands peering energetically down a narrow road that splits a once arable field, now become wasteland.

There is something important about the artist being within the zone, a kind of posturing that could be interpreted as egoistic martyrdom but is probably more to do with compassion, even solidarity. The visual fact that he was there, within the zone for days at a time, moves the work beyond the observational and gawking and into a poetic mode of drudgery and toil.

You’ll go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on is more than glib contemplation of man alienated from nature, the kind a documenteur like Werner Herzog might create when confronted with something unheimlich. The four works have more of an individual and, yes, anxious disposition that respectfully reenacts the precarious drollery of day-to-day sacrifice performed by the worker, the soldier, the farmer.

Systemic failure wrought its first and most vicious assault on the system’s own cogs: the people placed by circumstance or direct order within the exclusion zone at Fukishima seven years ago, some who linger.

“You almost feel it,” says Doctor of those who remain tied to the zone, “the dread. They’ve got to continue through this.”

You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on is showing at Chalk Horse gallery, Level 3, 77-83 William St, Darlinghurst from March 1st to 21st. A panel discussion with Sam Doctor and Stanislava Pinchuk (aka Miso), mediatated by Dr Oliver Watts, will be held on March 15th at Chalk Horse in conjunction with Art Month.