It’s 9.30am, I’ve just left home, and I hit a 100-metre queue at the lights. My pulse quickens. I divert through suburban streets, only to face a 200-metre tailback at Bathurst Street going into the city. Panic! No way I’ll be on time. I thought 30 minutes was enough to drive seven kilometres. I take the Cross City Tunnel, whizz through Paddington and East Sydney, and into Surry Hills. I’m on time! But there’s no denying. I’m a rat-runner.

Get used to it. Overcrowding will continue to fuel traffic jams, rat-runners avoiding tolls and the housing affordability crisis. We’ve only just begun to see the impact of rapid population growth in Australia over the past 15 years. Without proper investment in infrastructure, Sydney will grind to a halt.

This is not about WestConnex and other flurries of activity. It’s about the built-out areas where roads cannot be expanded; about cramming people into suburbs that are not being equipped to take the growth; about turning King Street, Newtown into a transport sewer. It’s the Saturday traffic jams that suck away precious free time. We’ve passed the time to slow the human tide that pumps millions of new people into Australia’s major cities every few years, especially Sydney.

Sydney is expected to grow from 4.7 million to 5.1 million between last year and 2021. That’s nearly 2000 new residents a week. This is due to the federal government running migration at up to 240,000 a year. More than half of these migrants come to Sydney or Melbourne. Australia’s population is projected to grow from just over 24 million to 40 million by around 2055. Since the government plans to keep the tap on fully open, the population of Sydney will keep increasing.

With so many people coming to Sydney, strong demand for housing is guaranteed, experts say. All the politicians’ talk about boosting housing supply seems fanciful in the face of this demand. It’s time to pause and ask “Who benefits?” If rapid population increases help keep property prices high, and growing, there are no prizes for guessing which business interests support Big Australia. Big businesses.

The big end of town drives demand for high population growth, the former federal Labor MP Kelvin Thomson argued recently. Property developers and the building industry want more consumers in Australia, as well as downwards pressure on wages and conditions. Accusations of racism, Thomson says, are among the ammunition supporters of rapid population growth use to shut down debate.

Others echo this relatively unpopular (among elite circles) line. Dr Jane O’Sullivan, Queensland president of Sustainable Population Australia, pinpoints the vested interests that strive to maintain inflated property values. These people and corporations drive the largest single source of political donations, O’Sullivan told NEIGHBOURHOOD.

The ABC’s political donations database reveals that last financial year, the Liberal Party received $170,000 from apartment developer Meriton, owned by Australia’s second-richest person, Harry Triguboff. The other major party, Labor, received $152,000 from shopping centre giant Westfield, which is owned by multi-billionaire Frank Lowy, Australia’s fourth-richest. And, of course, millions went to both parties from banks and other financial interests, which benefit greatly from high property prices (more borrowing).

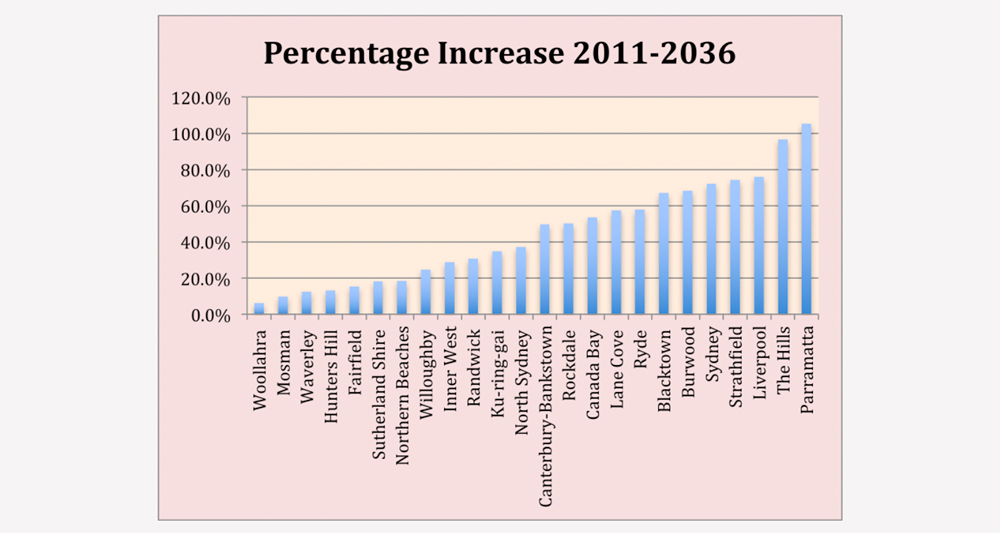

While one person’s overcrowding is another person’s waist-trimming densification, it is clear that some richer areas are protected from growth. The new Inner West Council’s population will increase by 20,000 in the next 10 years, with a corresponding increase in dwelling numbers. Yet the smaller Woollahra Council will increase by just 650 people (see graph 1).

GRAPH 1: POPULATION BY COUNCIL AREA

Statistical source: NSW Department of Planning and Environment

Woollahra Council happens to include Point Piper, harbourside home to the Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, who is a Big Australia supporter. Turnbull is not interested in stabilising populations,

Former NSW premier Bob Carr has long argued against overpopulating Sydney and Australia. “Business should stop imagining it can have lower corporate tax rates and high immigration,” he wrote during the big population debate in 2010. High immigration requires more government spending, and therefore higher tax, he argued.

Carr raised environmental concerns when he noted that the business lobby wouldn’t back sustainability indicators such as linking population and immigration policy with progress on biodiversity preservation, water efficiency and housing affordability. “They are focused on the total size of the economy, a crude measure.” This is a key point. Many people highlight the growth in gross domestic product (a measure of the economy). But what is hardly ever discussed is GDP growth per head. That is, Australia is simply getting bigger, but each of us is not getting wealthier.

Consider it thus. If Australia is a household of 10 people whose economy is worth $1000, each person’s wealth is $100. If someone joins the household and helps its economy grow to $1100, each of the 11 people’s wealth is still only $100. The trick is to grow the economy per head. A host of researchers agree this point is crucial.

Actually, gross domestic product per head is itself only a rough measure of wealth per person. The Australian Bureau of Statistics says the best way to measure whether we are getting wealthier is to use trend estimates of real net national disposable income per capita.

Take the past five years. From the end of 2011 to 2016 was a time of rapid population growth. But real household living standards did not rise in that time, according to analysis by Professor Peter Whiteford in The Conversation last year. Think about that. More than 1 million people arrived in Australia in that five years, most of them ending up in Sydney and Melbourne, and we are less wealthy (per head) in real terms.

In fact, the critical factor in increasing wealth is not to grow the size of the pie, but to improve productivity. Productivity is a key to generating growth per capita, that is, to growing wealth. Too much immigration, however, threatens our productivity, according to economics writer Ross Gittins: “The very report announcing that our population is projected to grow by 16 million to 40 million over the next 40 years doesn’t say a word about the huge increase in infrastructure spending this will require,” he wrote in The Sydney Morning Herald.

The overcrowding we experience in Sydney each day is a symptom of this underinvestment. The state government fails to adequately plan for health services, schools, aged care and open space when it increases density, former Labor mayor of Leichhardt Darcy Byrne told NEIGHBOURHOOD. “Ongoing increases in residential density are based on an assumption of no cars. That’s going to result in even more congestion.”

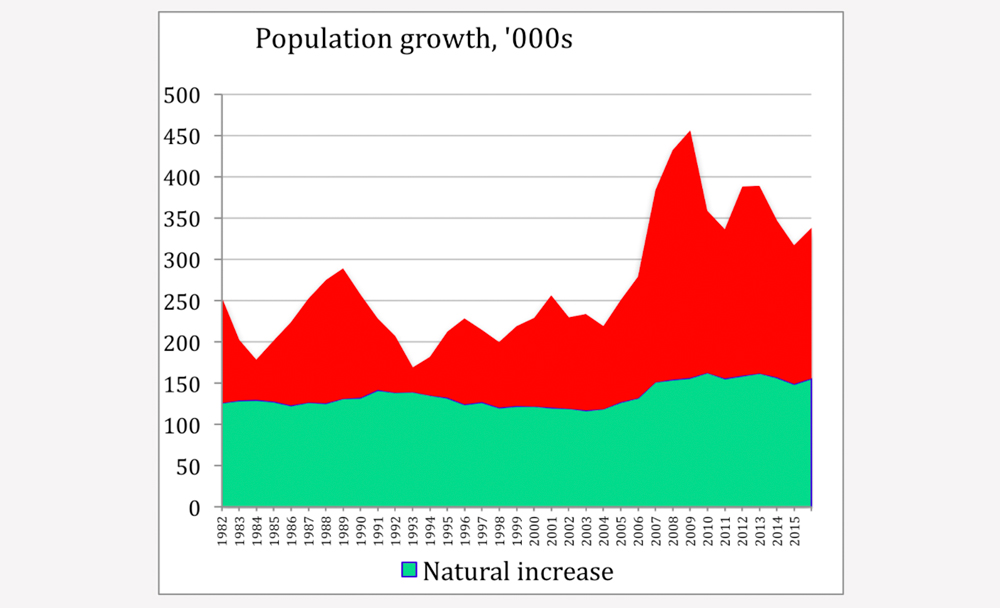

More congestion, and more unaffordable housing. The federal government guarantees strong demand for housing by running net overseas migration up to 240,000 a year, demographer Dr Bob Birrell’s report No End in Sight says. There are two main factors in population growth: natural increase (births minus deaths) and net overseas migration (long-term arrivals minus departures). Migrants will add about 64 per cent to the need for extra dwellings in Sydney between 2012 and 2022, Birrell’s projections show. At current rates, either more homes and infrastructure are built, or prices and congestion increase. At the moment, it’s the latter.

The elite support for Big Australia is buttressed by right-wing think-tanks, which fund fledgling pundits to write articles such as “Five reasons Australia should be big”. They highlight positives such as labour participation rates of 77 per cent for migrants with Australian citizenship compared with the national average rate of 65 per cent. “Claims that migrants are a net pressure on welfare payments do not stack up,” wrote Patrick Carvalho in ABC’s The Drum. “Migrants are likely to be working.” While that statistic might address the welfare argument against immigration, it doesn’t address wealth per capita.

Similarly, Big Australia supporters also argue that the ageing population is a crisis, based on projections that the number of Australians aged over 65 will double by the 2050s, exerting more pressure on budgets. They say the nation needs enough young, skilled migrants to continually keep the books balanced.

Again, plenty of contrary evidence exists. Immigration does not particularly help lessen the ageing of our population, according to the Productivity Commission’s report Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth. “Net overseas migration is contributing about half of Australia’s population growth and is marginally raising the proportion of ‘younger-aged’ working people in the population, with little impact on the ageing of the entire population,” the report notes. Boosting migration further won’t help either, it says. “An increase in the current levels of net overseas migration, however, would have little impact on ageing.”

So why take so many migrants despite flimsy evidence of the benefits for average Australians? Australia’s leading econocrat places the answer in its context – globalisation and competition. Dr Philip Lowe, governor of the Reserve Bank, said in 2014 that creating a “productive, globally competitive economy” depended on building on foundations such as “strong overall population growth”. By 2024, Lowe forecast, Australia’s population would be 17 per cent higher than in 2014, an extra 4 million people. “These people will require somewhere to live, to work and to play.”

Sustainable Population Australia’s Dr O’Sullivan describes such justifications using growth, increasing labour supply, and countering demographic ageing as “Ponzi-scheme economics”. They don’t contribute much to the common good, she says, but shift wealth “from the many to the few, from the younger to the older, and from future people to current people”.

The pie may be getting bigger, but who is eating it? Think about that next time you’re stuck in traffic. To address sustainability, densification and economic growth, we can either slow population growth or raise taxes/debt and share the costs of growth. It’s one or the other. “None of the above” is not an option.

GRAPH 2: AUSTRALIA’S POPULATION GROWTH, 1982-2016

Image source: Australian Bureau of Statistics and Dr Katharine Betts. (net overseas migration + natural increase)

Jock Cheetham is a senior lecturer in journalism at Charles Sturt University.