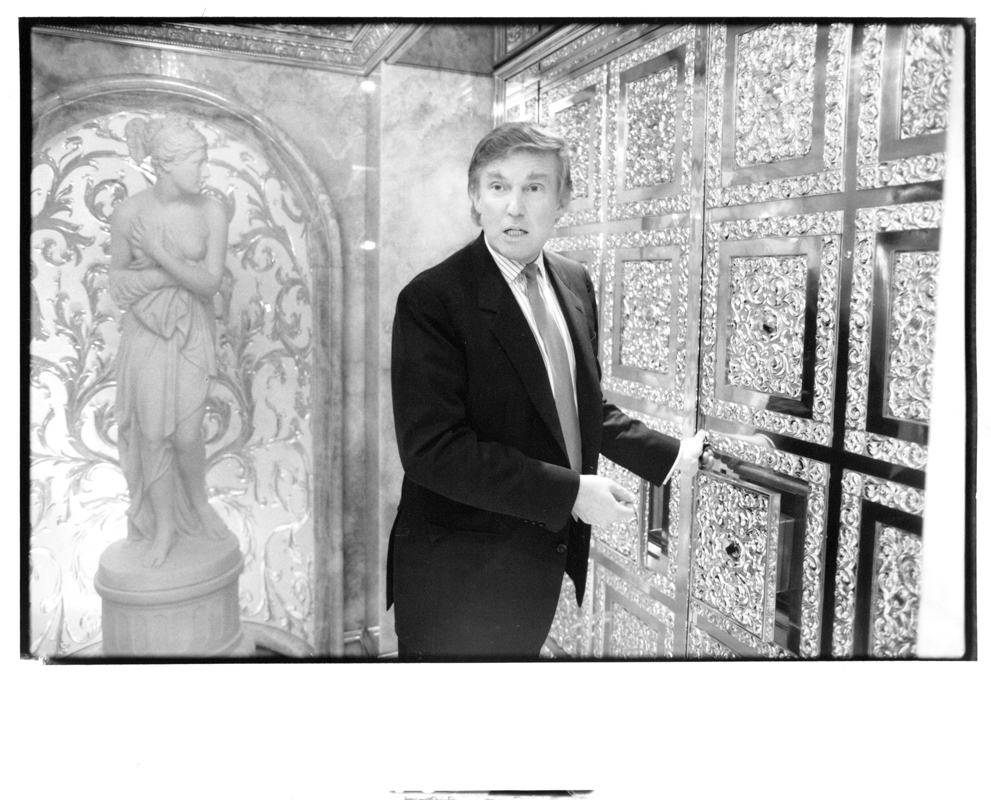

The leader of the Free World is a man who, as Newsweek recently reported, has thrice been accused of rape and attempted rape, of sexual assault or harassment by at least sixteen women, and of spousal violence. He was accused of rape in a sworn deposition in 1991, years before any presidential ambitions were evident, making it clear that no political motivations were involved. He is also a man who has bragged of sexual assault without consequences as one of the benefits of celebrity.

The fact that such a man was voted president by 53% of white female voters tells us one thing: that the capacity for intimacy is no longer considered an important attribute in a leader, even by the demographic associated with the nurturance of infants.

Those who voted for Donald Trump would argue that the capacity for intimacy is not only unrelated to the demands of public office, but hostile to them, not understanding that a capacity for intimacy is pivotal to long-game management in any situation. Without it, discord, both civil and in relation to other territories, as Trump’s mismanagement of the United States has shown.

Since his election to office, there have been, among others, 673 organised global women’s protest marches against his presidency, the biggest single-day protests in US history.

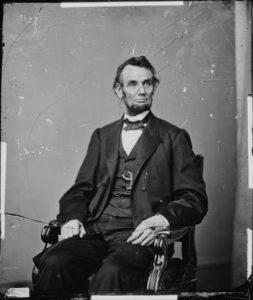

Intimacy is the cornerstone of humanity – not merely in the domestic sphere but politically, as our greatest and most inspiring leaders have demonstrated. One only has to consider the impact of Abraham Lincoln on the world to understand the significance of intimacy and the empathy that flowers from it.

Lincoln signed the first Homestead Act, allowing the poor to own land. He established the US Department of Agriculture, referred to as the ‘People’s Department’. He signed the Morill Land-Grant Act, which led to the construction of the greatest colleges and universities in America. He signed the Revenue Act of 1862, dividing taxpayers into income-differentiated strands, and his Emancipation Proclamation was the forerunner of the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery and indentured servitude.

His every achievement was a byproduct of intimacy, that fragile emotional biosphere which flourishes only with consistency and tenderness.

Lincoln’s early life was marred by trauma – notably, by the death of his mother and that of his sister, who, in tandem with his stepmother, had taken turns in nurturing him. The deep, tender, reciprocal love he shared with these women not only imbued him with a resilience that enabled him to survive adversity but was translated by him into a passion for humanity that would revolutionise the world. He said, “All that I am, or hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.”

Unlike Trump, Lincoln was not merely a politician but a statesman – thoughtful, respected, and able to be profoundly moved, a man who served rather than dominated the world. Without a capacity for intimacy, politicians can have no real concern for the impact of the economy on families or the way in which government policies affect individual lives.

Abraham Lincoln, President, U.S. 9 February 1864. Credit: Mathew Brady [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Critically, without an understanding of a child’s fundamental need for intimacy and the way in which this need, particularly when frustrated, plays out, politicians harm not only those they govern but innumerable future generations. One only has to address certain policies – Trump’s repeal of the Clean Power Plan, originally created to combat global climate change, for example – to understand the wider implications of ruptured intimacy. Without intimacy, there is no vision.

Those who have not experienced intimacy – childhood friends of Trump noted his real estate developer father’s global parsimony and his mother’s socially ambitious “reserve” – literally do not understand what it is to live in love; instead, they understand only conquest and the adrenaline-fuelled drive to earn approval.

A neighbour recalled catching the young Trump, the fourth of five children and clearly jealous of his younger sibling Robert, using her baby son’s playpen for “target practice” with rocks. Known for his desperation for attention, the “wiseguy” Trump was, at thirteen, expelled by his father from the world of limousines and 23-room childhood homes and enrolled in a military boarding academy known for its strictness and corporal punishment. Tellingly, one of his teachers later noted that Trump “wanted to be number one. He wanted to be noticed. He wanted to be recognized. And he liked compliments.” Far from being extinguished, Trump’s anger only intensified at the school. He attempted to shove a fellow cadet out of a second storey window; he destroyed a baseball bat; he bullied.

Trump’s appetite for the humiliation and degradation of those he regards as inferior has remained consistent. During a 2011 interview, he attempted to justify this sadism, recalling that, “I dealt with [former Libyan president Muammar] Qaddafi. I rented him a piece of land. He paid me more for one night than the land was worth for two years, and then I didn’t let him use the land. That’s what we should be doing. I don’t want to use the word ‘screwed’, but I screwed him. That’s what we should be doing.”

The same approach is applied to all those who dare critique him. In 1992, Trump told New York Magazine that “you have to treat [women] like shit”; in 2011, he wrote that journalist Gail Collins had “the face of a dog”; in 2015, he bragged that he’d “knocked the shit” out of performer Cher on Twitter – all this in addition to abusing and belittling various female detractors (“disgusting animal”, “a big, fat pig”, and so on).

As he once said, most people “aren’t worthy” of his respect.

Trump’s view of the world can be reduced to three words: win or die. There is no room in his philosophy for long-game thinking, only the imposition of will. It certainly makes for better sound bites, and Trump is nothing if not well-versed in the language of media. Importantly, the opponent must suffer as he was made to suffer.

He believes that being feared is safer than being loved as man’s nature is, as the fifteenth century philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli wrote, “ungrateful, fickle, false, cowardly, covetous” (here he could have been describing Trump). This philosophy – now part of the corporate canon – precludes trust, the bedrock of intimacy, and yet the capacity for intimacy is the most relevant quality in any leader, for the love of one’s people is only made possible by the ability to place another’s needs before one’s own.

Our culturally ratified and essentially anti-human dis-integration – a philosophy encouraging the perception of mammalian devotion and vulnerability as inferior to reptilian self-interest – is evident in every sphere, from the corporate to the intimate. The complex, delicate human neurobiological mechanism doesn’t stand a chance against such heavy weather. At every turn, status above love.

Given this, it’s unsurprising that 88% of blacks and 65% of Hispanics voted against Trump: both ethnic groups are known for the intensity of their maternal-infant bond. When I interviewed psychologist Steve Biddulph for my book Mama: Love, Motherhood and Revolution, he noted that upper-class American women prefer Hispanic nannies. “The cultural capacity for love can be lost,” he explained. “We are outsourcing love to the Third World.”

The biological psychiatrists who wrote A General Theory of Love noted that passion is now regarded as “a troublesome remnant from humanity’s savage past” and that, conversely, civilization is now seen as the triumph of logic over affect.

But as the philosopher George Santayana pointed out, logic would be meaningless had it no emotional value. “Things are interesting because we care about them,” he wrote. Without this investment of feeling, life itself would be without worth. Far from being redundant, the affective architecture of our brains is thus pivotal to our species’ evolution.

Trump’s hallmark is the rage of the ignored child, a child ignored in favour of status-currying and achievement, a child forced to compete with his siblings for attention. In part, this undoubtedly accounts for his popularity with white Americans raised as he was raised: without tenderness, warmth or empathy.

When journalist Mark Singer interviewed Trump for The New Yorker in 1997, Trump said, “You really want to know what I consider ideal company? A total piece of ass.”

Donald Trump. Credit: Gage Skidmore/Flickr

Given the opportunity to spend time with the world’s greatest artists or visionaries, Trump, a boy whose need for intimacy with his mother had been fatally frustrated, would prefer to be with a “total piece of ass”. He expressed the same longing to

The capacity for intimacy is primarily determined by the infant’s primary caregiver, who acts as the source of that which researchers refer to as “affective transmissions” or “transactions”; at their highest octave, these transactions are what is otherwise known as love, and mature areas of the brain associated with socioemotional function.

Maturation of these structures also aligns infant motivation to adult feeling, resulting in the mutually respectful and beneficial harmony that came so easily to Lincoln and that is so alien to Trump. As neuropsychologist Dr Allan Schore observed of maternal-infant intimacy, “these early social events are imprinted into the biological structures that are maturing during the brain growth spurt that occurs in the first two years of human life, and therefore have far-reaching and long-enduring effects.”

Schore explained the process as the child downloading the output of the mother’s right cortex, on which he will then model his own development. In themselves, these maternal/infant exchanges are imprinted as the subconscious template for all other exchanges, determining each man’s response to Albert Einstein’s fabled statement: “The most important question you can ever ask is if the world is a friendly place.”

Trump’s response to the question was predictable. “The world is a mess,” he said. “The world is as angry as it gets. What, you think this is going to cause a little more anger? The world is an angry place.”

He was, of course, not talking about the world, whose beauty can be defined in innumerable ways, but about his mother, whose anger he internalised and which now defines him. Trump’s immigrant family of origin was archetypal in terms of its dysfunction: unyielding, mistrustful, insensitive, conformist, highly disciplined, dysfunctional. His older brother Frederick Jnr acted as the catchment area for the family’s aggressively disguised depression: a chronic alcoholic, he imploded, dying of alcohol-related complications at the age of 43 in 1981.

Human beings are designed to love and to trust; when love and trust are absent, we implode in any number of ways. The independence to which recent generations have been conditioned to aspire is a fiction; as psychiatrist Bruce Perry wrote, “the truth is there’s not a single human on this planet, ever, that’s been independent. All of our physiology is designed to connect to others, we have huge parts of our brain designed purely to respond to the non-verbal cues of others … it’s in the way our face is oriented, our facial configuration is forward, looking at people … We have sensory apparatus on our skin that’s meant to be touched … so that we can feel somebody caress us.”

Ours is a secular culture, and yet the Christian hangover – in terms of the intrinsic wrongness of human beings and of the sinful nature of the flesh – continues to poison the world, causing us to associate sexuality with disgust (the key to pornography) and maternal/infant intimacy with inferiority.

The intense reaction certain people have to the nurturance of children and breastfeeding in particular evidences the depth of this wound; such people cannot be exposed to it without experiencing an anguish that manifests as disgust. In 2011, lawyer Elizabeth Beck asked Trump if she could take a break from a deposition to pump breastmilk for her newborn. Trump reported, “She wanted to breast pump in front of me and I may have said that’s disgusting, I may have said something else. I thought it was terrible.”

Beck denied suggesting pumping milk before Trump – there were other lawyers present to corroborate her account – but remembers the bizarrely charged vehemence of his reaction.

“He completely lost it,” she said, recalling that he started to “shake, his face got really red, he pointed his finger and shook it and said, ‘You’re disgusting! You’re disgusting!’ Then he bolted and no one saw him again.”

Our aspiration to the incorporeal – again, this is the axis of pornography and of technology in general – is a tragedy. In promoting insensitivity and inhumanity as the ultimate goal, we’re not only losing our understanding of what it is to be human but our ability to feel passion and joy.

The most interesting aspect of Trump is that despite being the son of a wealthy man, handsome in his youth, famous, feted by beautiful women, a reality TV star, a billionaire, the father of an array of healthy children and – improbably – now the leader of the Free World, he never looks happy. He looks smug, charming and vindicated, but never happy.

Mostly, he just looks angry. Derision and near-universal lack of respect may well have embittered him, but one thing is clear: unlike Lincoln, whose assassination triggered unprecedented public sorrow, Trump has given up on intimacy. He now knows for certain that he will never be loved in the way he should have been loved. And it hurts, because if it didn’t, he wouldn’t be so angry.

Antonella Gambotto-Burke is the author of The Eclipse: A Memoir of Suicide and Mama: Love, Motherhood and Revolution. She can be contacted through antonellagambottoburke.com

‘Mama’ by Antonella Gambotto-Burke