I’m in a conversation inside a car inside a song. I say we’re inside a song – as much as a car or a conversation – because the lyrics to ‘Higgs Boson Blues’ seem to define what the rock musician Nick Cave and I are passing through as we cruise on down a highway north of Sydney towards a show with his band the Bad Seeds in the coastal steel-town of Newcastle.

In the actual song, Cave fantasizes about “driving down to Geneva” where scientists anticipate an experiment that will isolate the Higgs boson or so-called ‘God particle’ that is the sub-atomic building block of all matter. A litany of historical and pop cultural images are mashed together in an imagistic contemplation of a universe being steadily emptied of all spiritual illusions.

Right now, I feel strange echoes of the same “black road long”, half inviting, half swallowing us; of “tableaus of spiritual collapse”, as Cave has described ‘Higgs Boson Blues’, fleeting past the corners of our eyes in new ways this oppressively warm afternoon.

For all his recent talk of no longer writing narrative lyrics, the truth is Nick Cave is still telling us stories in songs like ‘Higgs Boson Blues’ and eerie, recent stunners like ‘Magneto’. They’re just more expressionistic, subconscious, dreamier and deeper, maybe, than before.

It’s certainly interesting to hear Cave admit, “I can’t write a song that I can’t see.”

He nonetheless insists, “I haven’t much time for overtly narrative songs these days. It has felt hugely restrictive for some time. The idea that we live life in a straight line, like a story, seems to me to be increasingly absurd and more than anything a kind of intellectual convenience. I feel that the events in our lives are like a series of bells being struck and the vibrations spread outwards, affecting everything, our present, and our futures, of course, but our past as well. Everything is changing and vibrating and in flux.

“So, to apply that to songwriting, [in] a song like ‘I Need You’ off the new album [Skeleton Tree], time and space all seem to be rushing and colliding into a kind of big bang of despair. There is a pure heart, but all around it is chaos.”

Cave’s Australian tour this last January mark his first live performances since the death of his 15-year-old son Arthur from a cliff fall in Brighton after experimenting with LSD on the 14

At each live show a predominantly instrumental electronic piece serves as a prelude to the band. The music suggests a wind-churned netherworld in which Cave’s voice rises up in a Dante-esque incantation that is hard-to-catch… something about “Far from your eyes in a place where winter never comes… And all along the wind I run… And I return to this place… And all along the wind I run.”

In the car, Cave requests this track no longer be played before he is about to go on stage. His tour manager explains that Bad Seeds band-leader and song-writing collaborator Warren Ellis has arranged it “specially” for the group to hear before they begin each concert. Cave considers this very slowly and quietly, then asks that he be called a few minutes later so he does not have to stand side-of-stage and listen to it every time. Problem solved, he lightens the decision by naming such situations ‘The Slaughter of the Mojo Fairies’. “It’s so easy to go from ‘oh yeah’ to ‘oh no’ just before you go on stage.”

A type of stage fright might also suggest the nerves people feel in trying to meet Cave eye-to-eye in any conversation about his lost son Arthur. Yet Cave has been relentlessly upbeat for the shows on this tour so far, almost released of a burden and obviously glad to be performing again. Seeing him backstage after sprawling and exultant shows that are nothing short of communal celebrations of life, there’s a spark and warmth in his eyes and conversation that is pleasing to behold and quite unexpected. Arthur’s twin brother, Earl, now 16, has got Cave into The Smiths. “Do you like them?” he says, like they are absolutely the latest thing. “Great lyrics.” Curious, charged, Cave is somehow brighter than ever.

He turns to me in the car now and says, “We’re going to have to talk about Arthur for this, aren’t we?” I say of course. He asks if he can follow through with anything he might say by emailing me his thoughts. Speaking about it, things never come out the way he would like. “I don’t want to intrude on your independent Beat prose approach,” he adds with a playful spike. Then he talks about the way I take notes – how in interviews he starts to see everything he says appearing as text before his eyes and it becomes hard to say anything at all that’s true. “But if I could just write something in response to anything I say, or develop a quote better with an email later I’d really appreciate it.”

Sure, I say to him. Sure.

Cave goes on, “The thing is – I feel like there are things I’d like to say about Arthur, but I’ve been too frightened to say them.”

He admits that just two months before this tour he suddenly took to bed, unable to get up. “It just sort of all came down again.”

Suddenly, the presence of someone very big and alive seems to fold and contract. The image of a wilted black flower comes to me as I observe him quieten into himself. Another of Cave’s favourite lines, from Philip Larkin’s The Mower – oft quoted by him over the years – springs into my mind in a wild burst of empathy: “The first day after a death, the new absence / Is always the same; we should be careful /Of each other, we should be kind / While there is still time.”

Nick with songwriting partner Warren Ellis of The Bad Seeds, performing live. Image courtesy of Nick Cave.

Lovely Creatures – The Best of Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds

He tells me he is already writing new songs. “Not to answer Skeleton Tree,” he emphasizes, “but to artistically complete the trilogy of albums we began with Push the Sky Away.” In between when we speak and this article is written, a mere matter of months, I get word Cave and Ellis are releasing their soundtrack for the National Geographic series MARS, and that Cave has written a children’s story. There are another five soundtracks spilling out. Preparation for the new album continues apace – as do other soundtracks and collaborations.

When we meet a day later at Sydney hotel to do our interview proper I remark that after Arthur died I would not have been surprised if Cave had felt what’s the point?

Lovely Creatures was ready for release two years ago, but its nature as retrospective celebration suddenly felt entirely wrong – and Cave put the whole project away after an enormous amount of love and care that had involved him in everything from the graphic design, to editing together both a DVD of rare moments and a book of essays from the likes of NME photographer and journalist Bleddyn Butcher, Melbourne arts writer Gerard Elson, rock ‘n’ roll diarist and author Larry ‘Ratso’ Sloman (the inspiration for the song ‘Dig, Lazarus, Dig’) and film critic Yoram Allon. The deluxe edition of Lovely Creatures includes an extremely lavish array of never-seen photos and page-marking bric-a-brac (celluloid snippets, scrawled lyrics, hand-drawn artwork from notebooks) that must have cost a fortune to reproduce.

“What’s the point?” he says back to me. When Cave repeats something you feel a prickle of rebuke in the room. “No,” he says, “I never felt that for an instant.”

“I think I talked about this in the movie – but this whole thing about there being no imaginative space to sit down and actually write about something, that was a problem,” he says. “Like there’s just this thing, and there’s no way to navigate it. It just sits there and it fills up all the space. It fills up your body. It’s like a physical thing. You can feel it pressing against the insides of your fingers. There’s just no room for the luxury of creation.”

“I don’t feel like that anymore, I have to say… I feel I am in a very good place with lyrics. I work differently these days. I have abandoned my office completely and am finding great pleasure sitting at the window in my bedroom, surrounded by my books and just thinking and writing words. I am not worrying too much about writing actual songs as such, rather just amassing a stockpile of lines and thoughts, images and ideas. I feel I have turned a corner and wandered onto a landscape that is open and vast. The ‘sweet prairies of anarchy’ as [the English poet] Stevie Smith says!

“I haven’t written anything for over a year, quite deliberately. I wrote a bunch of songs after Arthur died, but I felt they were somehow a betrayal of what we were all going through at the time or worse, a betrayal of Arthur himself; that they didn’t possess the required emotional reach, so I scrapped them. But Andrew Dominik found them in my notebooks and loved them and used some of them for voice-over in his film One More Time with Feeling. I can see now, with a bit of clarity, that there was something powerful about them that I was unable to see at the time. Anyway. they are floating around. But I am writing new stuff. Lots of new stuff.”

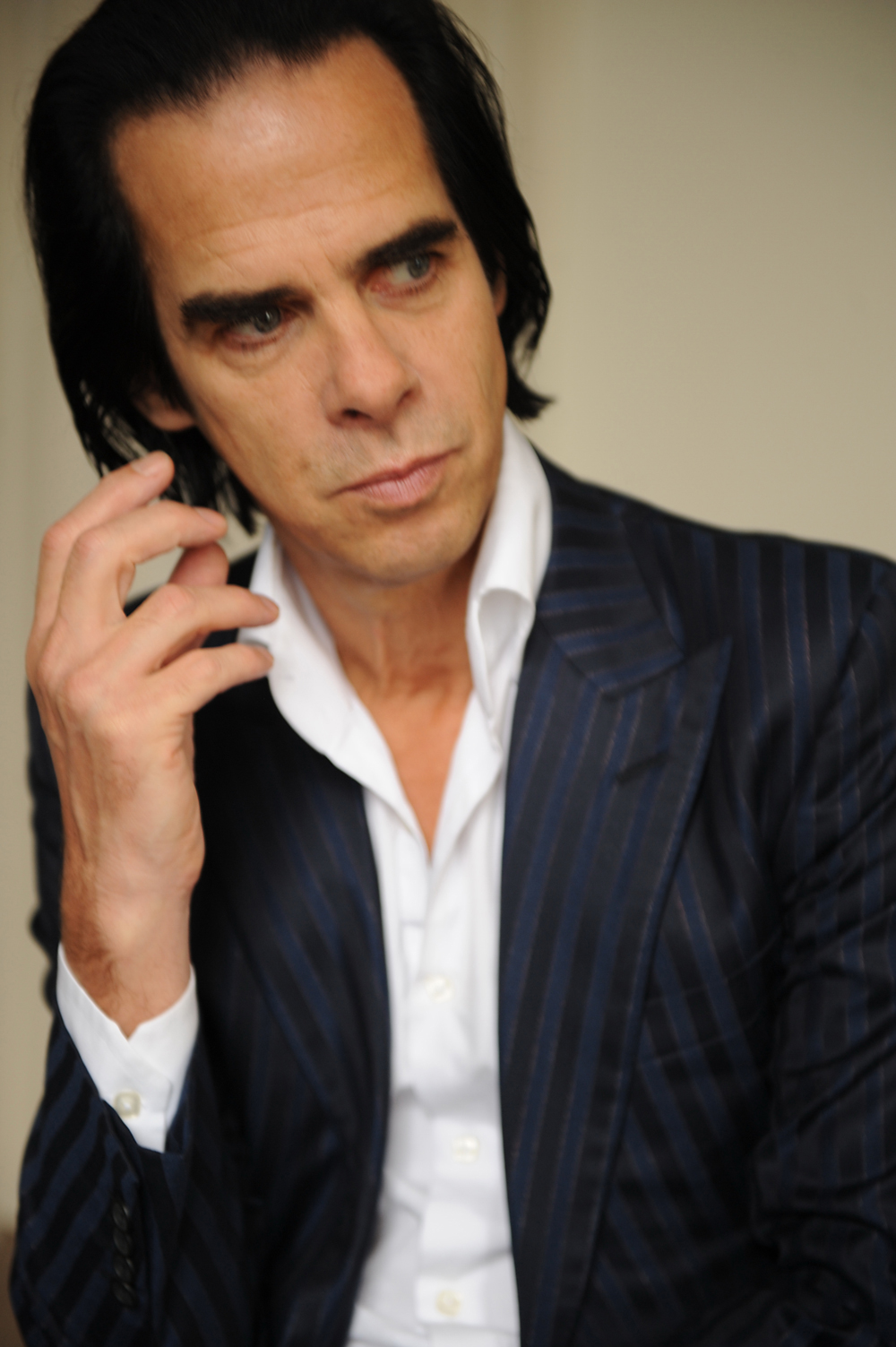

Nick Cave. Photography by Bleddyn Butcher

Listening to the remarkable trajectory of

I had wondered if tragedy might diminish Nick Cave’s work, making the past feeble and histrionic in comparison to the wounded visions of the present. But the work, it seems, has come forward to meet him just as strongly. Reflecting again on Arthur and any meaning that might be found, Cave says, “It’s hard to know what to say that is helpful. People often say they can’t imagine how it would feel to lose a child, but actually they can, they can imagine what it is like.”

“A lot is said about grief, especially the conventional wisdom that you do it alone. I personally have found that not to be the case. The goodwill we received after Arthur’s death from people that I did not know, especially through social media, people who liked my music and kind of reached out, was extraordinary. This had much to do with Andrew’s film and I will always be indebted to him for this. The rush of emotion it unleashed in people and the way they wrote about their own sadnesses and their own griefs was monumental and amazingly helpful for me and my family.

“Initially, I thought it would be impossible to do this in the public eye. The impulse was to hide. But it turns out that being forced to grieve openly basically saved us.Of course, there is something that feels almost heroic about suffering on your own, to be locked into a world of memory, almost a nobility, I understand this, but it is an illusion and a very dangerous, life-threatening situation to put yourself in. Susie and I have grown to understand this. We are vigilant around each other, watchful that we don’t shut down.”

Cave feels it’s important to talk about his wife Susie Bick’s work on her successful fashion label, The Vampire’s Wife. “I’m really, I’m just really blown away by Susie, by what she’s become over this last year – or what she’s managed to do. Seeing it from a different point of view, the incredible healing act of work. It’s not just… in the film it came over as – when Susie talked about it – a distraction. It is that, but it’s actually helped her and – as much as something like this can ever be healed – it’s brought her out of the kind of treacle of grief that we were trapped in a beautifully creative way. That’s been something inspiring and very helpful for me to see.”

Returning to work himself, returning to the songs on Lovely Creatures and performing them live, more than he could ever have imagined has occurred. “I haven’t gone near these songs in years. Some of them, I’m literally shocked to find that their meaning has changed completely to me. They suddenly mean something else entirely. Like ‘Into My Arms’ or something like that. It just suddenly feels like I’m not singing it to whoever, it’s –

Cave stops, then starts again. “You know I’m just telling you this, in a way, because one thing I don’t want is people having to come along and involve themselves in someone else’s drama. I don’t want the shows to be like that. I want the shows to be uplifting and inspiring and for people to walk away feeling better than when they came, not some sort of empathetic contagion that goes through the crowd and people walk out feeling like shit. I don’t want that. Because I’m not feeling that way. On stage I feel great. It just sort of feels beautiful and inspiring. The songs are strange things, you know. They’re patient, and wait for the meaning and then meaning changes through the years.”

An edited version of this story was first published by The Guardian UK under the title Nick Cave: ‘I have turned a corner and wandered on to a vast landscape’, 5th May 2017.