In a world where subcultural cool can be bought readymade, we admire most of all those people who seem to have created themselves from scratch. This is just how Patti Smith seems to us now; original, in a group of one, what they used to call a rugged individualist. But considering where and when she was brought up, this is a kind of miracle, or at least a very lucky escape.

Born in 1946, and raised in a semi-rural suburb of New Jersey, Smith’s adolescence played out under conditions that, some believed, would soon make individuality – rugged or otherwise – impossible. In his 1956 book The Power Elite, sociologist Charles Wright Mills worried that the growth of mass-media and suburban living had already transformed America from a nation of self-determining humans into what he called a ‘mass society’, in which radio, television and magazines tell us “who were are, what we want to be, and how to get that way.” As such, mass-people’s own views and opinions could not, in the end, be taken as their own, since “the media”, according to Mills, “have entered into our very experience of our own selves.”

This was certainly true for the teenage Patti Smith, living in Woodbury NJ. “Vogue magazine”, she later said, in a phrase to make Mills’ blood run cold, “was my whole consciousness”.

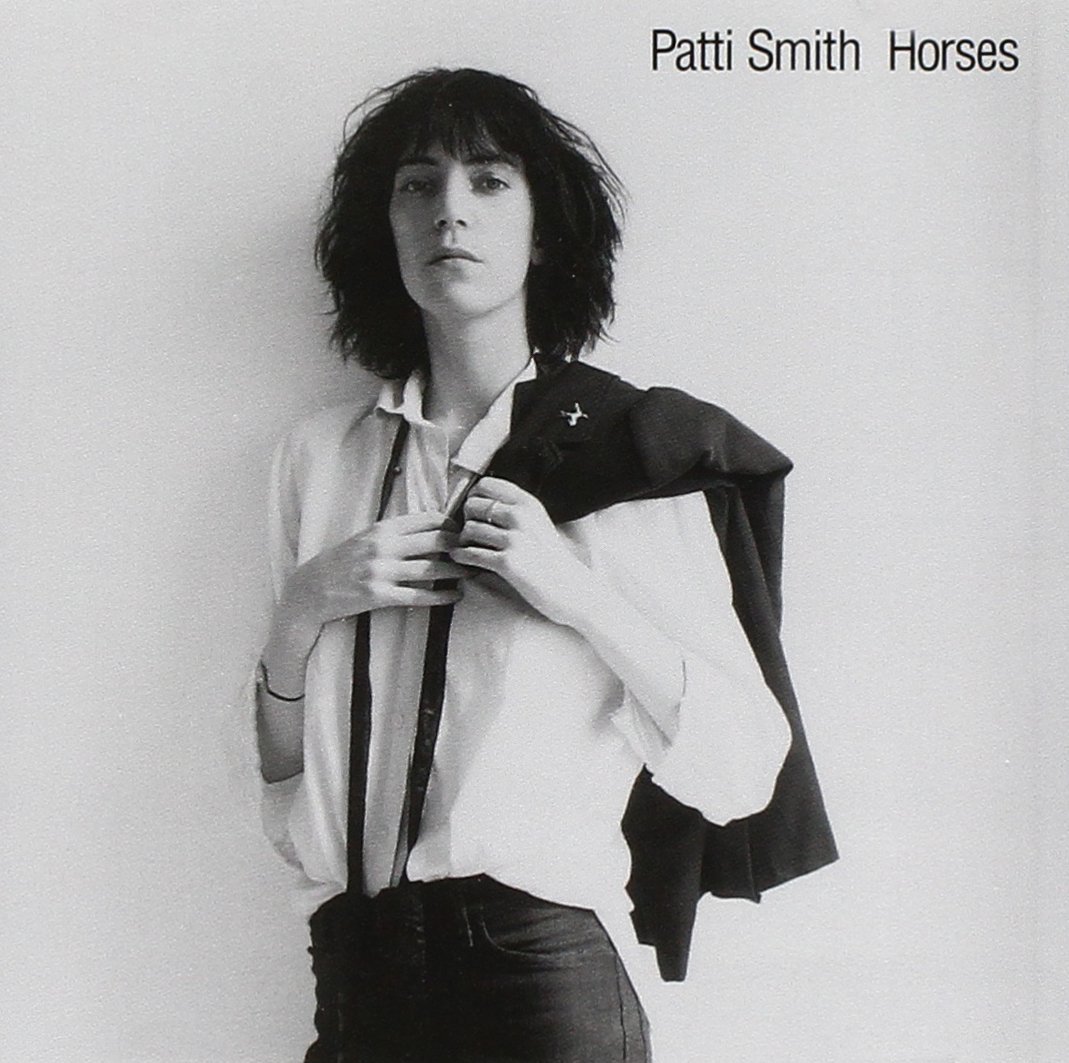

This quote might strike us as odd today, given the artist’s reputation as a non-conformist. But it rings true, possibly because Smith has always been a prolific creator and an uber-consumer. Horses, her astounding 1975 debut, is both suis generis and deeply fannish, a personal statement which is also a scrapbook of her adolescent fixations.

These include music, of course; the album features a tribute to Hendrix and an homage to Bob Marley, as well as huge chunks of other people’s songs, including Van Morrison’s ‘Gloria’, Chris Kenner’s ‘I Like It Like That’ and Wilson Pickett’s ‘Land of 1,000 Dances’.

There’s also literature: on the album’s centerpiece track, ‘Land’, Kenner and Pickett’s words segue dreamily out of a story inspired by William Burroughs’ The Wild Boys’, and into an invocation of late Romantic poet and professional hallucinator Arthur Rimbaud: “Life is full of pain, I’m cruisin’ through my brain and I fill my nose with snow and go Rimbaud, go Rimbaud…”

Even the cover, for all its startling originality, borrows from several other artists at once. “I didn’t have much money,” Smith explained in 1997, “I tried to dress like Baudelaire”. Smith had seen photos of the poet wearing a white shirt and black ribbon tie, and decided to do the same. Shortly before her friend Robert Mapplethorpe took the picture, he asked her to remove her jacket, and Smith, not sure what to do with the thing, suddenly recalled a scene from the end of the movie ‘Jokers’ Wild’, in which Frank Sinatra whips off his coat and slings it over his shoulder. The resulting image still changes people’s lives, but Smith, standing against that bare wall in 1975, had more modest goals. “I just wanted,” she said later, “to look cool.”

Patti Smith ‘Radio Ethiopia’ Photography by Judy Linn

Appropriately, Smith learned how to do this while working on an assembly line. In 1966, she paid her way through art college by toiling at a stinking hot Jersey pram factory, “inspectin’ a pipe”, as she later put it on her 1974 single ‘Piss Factory’.

The song is in many ways a dress-rehearsal for Horses, the album that would follow. In her lunch break, she’d sit in the basement and read Rimbaud – a scene out of a modern fairy-tale that’s almost too good to be true.

After all, Rimbaud and Baudelaire, according to historian Henri Lefebvre, represented the last gasp of a bohemian tradition that tried to preserve some part of humanity from the encroachments of industrialization, bourgeois domesticity and mass-society. But, Lefebvre argued, in the 20th century, this was no longer possible. Once artists and poets had become producers of commodities like everyone else, the old distinction between the boho and the bourgeois just didn’t count for as much as it used to, and the idea that there was some kind of essential difference between ‘high’ culture and the ‘mass’ variety, was virtually meaningless.

Smith, as if to prove Lefebvre’s point, bought her copy of Rimbaud’s Illuminations because she thought he looked hot in the photo on the cover, and daydreamed about him being her boyfriend. In other words, Smith treated art like it was pop, and listened to pop like it was art, and her hunch proved right on both counts. In a photo taken by Judy Linn of her apartment in 1970, the high and the low are fatally mixed up in a DIY shrine made from portraits clipped from magazines: opera singer Maria Callas lives next door to James Dean, Jean Genet meets John Lennon.

No doubt, you’ve made a shrine like this yourself at some point, or lived with someone who has. Patti Smith herself has likely featured in millions of the things.

And we all, to some degree ‘make ourselves up’ from such collections of mass-media images, borrowing a look from here, a hairstyle or a vocal mannerism from there. We’ve been doing it for so long, in fact, that the question of whether we’re expressing ourselves or imitating our idols when we do it has become academic – living in a media-saturated environment, we hardly know the difference anymore.

This, of course, is exactly what Mills feared in 1956, a society of people whose entire consciousness is shaped by media, and as such, can no longer distinguish between who they are and what they’ve been told to be. It’s precisely because of this that the old 19th century ideal of the self-expressing artist, the true individual, destined to be different, has such appeal today.

Smith herself is clearly fond of it. The figure who struts down the street in ‘Gloria’, who ignores square society and its “rules and regulations”, and exempts herself from a large swathe of human history by insisting that “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine”, is just one version of an ideal she’s presented to us throughout her career, an idealised version of herself.

“Some of us”, she said, “are born with a certain burning”.

This, she believes, made her fundamentally different from the mass-people she met at the ‘Piss Factory’, whose conformity had blinded them to what she refers to elsewhere as “the sea of possibilities”. “It just felt like a lot of people were happy to be like cattle in the factory and never rebel.” But the line she sings at the end of the song, when she dreams of turning her back on the stinking hot factory and catching that train to New York, shows her rebellion, more accurately, as not so much an escape from the process as its necessary reverse. “I’m gonna be somebody”, she wails, “I’m gonna be a big star”.

The year before she started working at the factory, Patti Smith bought the August issue of Vogue. Inside, her eye was caught by a photo profile on movie star and model Edie Sedgwick, and this small article would play a big role in the next phase of her life, propelling her out of Jersey and toward Manhattan with the promise of bohemia, art and adventure. “People are talking about YOUTHQUAKERS,” screamed the copy. Underneath was a picture of Sedgwick striking a ballet pose on a bed with a picture of a white horse in the background. “I thought ‘that’s it’,” Smith recalled. “It represented everything to me… intelligence, speed, being connected with the moment.” Smith knew that she couldn’t look or dress like Sedgwick, but that was hardly the point: the star was a somebody, she was herself, and Smith knew, looking at her, that she could be too.