There are very few balconies in Sydney where a pink waistcoat paired with Prince of Wales check and bowtie neither particularly amuses nor offends. One of those perches overlooks Moncur Street belonging to its eponymous bistro in Woollahra. Nestled at one of the handful of tables on the terrace of the eatery (which turns 25 this month), one can, politely, get away with practically anything.

I’ve collected my luncheon companion with virtually no warning but he is nonetheless resplendent in his obligatory, if typically paint-speckled black suit; it is my wardrobe which has emerged from the 1970s.

Tomorrow I bury my father. An hour ago I privately bade him farewell at an open casket viewing. I need a martini, Dad would have insisted.

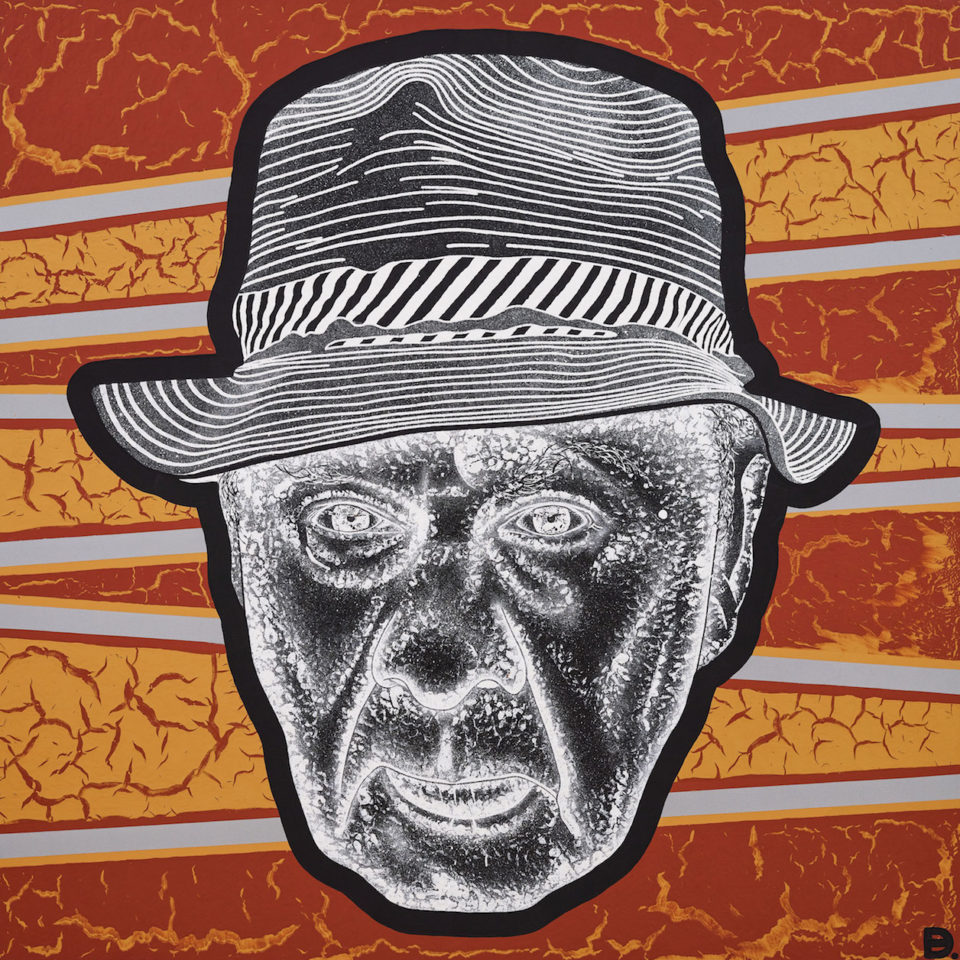

I am having lunch with McLean Edwards who met my father, the late art dealer Ray, when the young painter was precisely the age I am now. Son of a former Australian diplomat and extraordinarily well-read, McLean makes a fabulous dining companion one-on-one. Those who know the artist occasionally mistake him for an enfant terrible. His behaviour in public occasionally eccentric. The intensity of his intellect manifests in a frustration which lashes out, somewhat erratically, when confronted with the complacent niceties of society; an awkward trait to possess in a local art world that rewards the obsequious and inoffensive.

McLean was an early acolyte and student of another tortured soul whose personality occasionally bore those hallmarks, Keith Looby. An artist who I maintain is amongst the best the country has produced, Looby is virtually unknown to contemporary art aficionados. McLean’s earliest noted works from the nineties owe a lot to Looby; if not in composition or facial accents then certainly in the drawing talent both possess.

The most heroic period of McLean’s work so far are the big dark narrative pictures from the mid-naughties. This was a boom-time period for him when every investment banker in Sydney seemed to need to buy one – if only as a show of machismo in the face of their wives who insisted on filling their Paddington terraces with big doe-eyed Del Kathryn Barton canvases.

But it is the most recent paintings that I have most liked for a while. Small oil study portraits capturing the perfect essence of their subjects in a few strokes. Sitting across from Edwards I’m reminded of how he always looks like the protagonists in his paintings – today more so than usual. I have earmarked one of the new works on show at Scott Livesey in Melbourne to give to my wife for Christmas. I stumble through a sentence or two trying to talk about the show, to see how it is going, but for once neither of us particularly wants to talk about art.

McLean and I shared many fabulous lunches with my father at Surry Hills’ classic French diner Tabou, long since shuttered. My father and I turned occasionally to Bistro Moncur over the following years as the closest culinary cousin of our former favourite, but I am quite certain he always felt unfaithful; I’m more fickle.

Evan and Ray Hughes, Venice 1993. Photography by Annette Hughes

When the waitstaff hover to take an order all they draw from McLean and I is a request for two very dry Tanqueray martinis with olives. Through a fog of exhaustion and grief I haven’t much attention for a menu. I just need to be in the warm embrace of familiar company and am in dire need of a drink. I sense McLean, who is unusually laconic today, understands better than I that conversational voids are de rigeur at such times; he too only recently lost a father. Almost reluctantly, having not eaten properly for a few days, appetite having all but abandoned me, a dozen oysters each are sent for.

We drain our adequately well-put-together drinks and call for their prompt replenishment. Even morose and docile as a pair, we can be challenging to waiters. I say adequately, as this side of the Pacific Ocean it seems unfair to expect the perfectly mixed drink which so effortlessly emerges from the bar of even the crummiest eatery from LA to NYC.

Easting barbecue in a college rib-house in Atlanta with football on the screens and frat boys busily trying to outdo one another with oafishness, I still managed to procure that perfect martini, the oily residue of the contents sliding seductively up and down the sides of the glass. In Sydney one has to hope for something marginally short of rocket fuel. At the Woollahra, however (despite their upstairs bar turning literally to espresso martinis on tap) (no, really) whomever mixes the drinks downstairs at Moncur does one of the best jobs in town.

We’re onto our third by the time the oysters arrive and looking down at the plate I’m not instantly transported to Paris, thankfully. The clunky zinc oyster platters on their stands with their piles of crushed ice have become such a tedious cliché; like the sculpture of Louise Bourgeois, these are best and preferably only seen in Paris or New York.

Sometimes it’s nice to eat at a French restaurant and not feel like one is on the set of a Baz Luhrmann film. So I approve of the very simple way my 12 Sydney rocks arrive, clearly opened freshly, with just enough of their water retained by the shucker to let me know where they come from. An oyster which has been freshly opened retains its shape perfectly as it has not dried and still looks like it is a living creature. They’re my favourite things in the world to eat and were my dad’s also. Countless trips to the fish market to cater for his big gallery lunches: “Ten dozen… You can do a better price than that!” would bellow the man who never gave a discount in his life.

Up the stairs of Moncur bound the gallerists Tony and Roslyn Oxley; news of my father’s death has travelled widely in the artistic community and has been covered by all of the major newspapers. Tony looks somewhat aghast to see Ray’s only son out drinking and eating oysters with his playmate McLean Edwards before offering an understanding look of recognition that says: “Where else would one be to remember Ray.” It is that sort of place, Bistro Moncur, where art dealers, ladies who lunch, colourful lawyers and failed Labor politicians can all convivially share a meal and look down their noses at tedious but ubiquitous real estate agents who seem always to be relegated to Siberia down near the kitchen.

It’s sometimes hard to determine whether this restaurant is a rococo caricature or a perfectly pared back oil sketch of Sydney society, but it doesn’t really matter. The food is usually excellent. On this day I don’t feel like their à point sirloin, its salty-rich Café de Paris butter sauce or perfect French fries. Nor do I feel like one of the best, and simplest tomato salads you can order. Their smooth French onion cheese soufflé is not quite as good as Tabou’s was and though I normally would have one on the table alongside the faultless chicken liver mousse, today oysters and martinis are all I need.

McLean will go back to his studio and I will see him at the funeral the next day. He will be admonished for lighting a cigar in the middle of the Art Gallery of NSW during the afternoon service. I have drunk too much and haven’t eaten enough but it’s the fuel to get me through the final preparations for the following morning. Losing a father is hard enough, but losing your favourite lunch partner is a stark everyday example of what it entails. Today oysters and McLean let me know it might not be easy, but life will go on.

Bistro Moncur

116A Queen Street, Woollahra 2025

6 Tanqueray Martinis $120.00

24 Oysters $120.00

Total: $240.00