Working in commercial hospitality is hard. There’s a lot of bullshit about how wonderful seasonal produce is, how creative the plates are, and how inviting the atmosphere is. What lies beneath those aesthetic concerns is immense amounts of labour, often done by people who will never own the means of production.

The vast majority of chefs, waiters, kitchen hands and sommeliers will only ever have their labour to sell to others higher up the food chain. The industry depends on an endless stream of people who need the work, but couldn’t imagine anything worse than a career at the stove or on the floor.

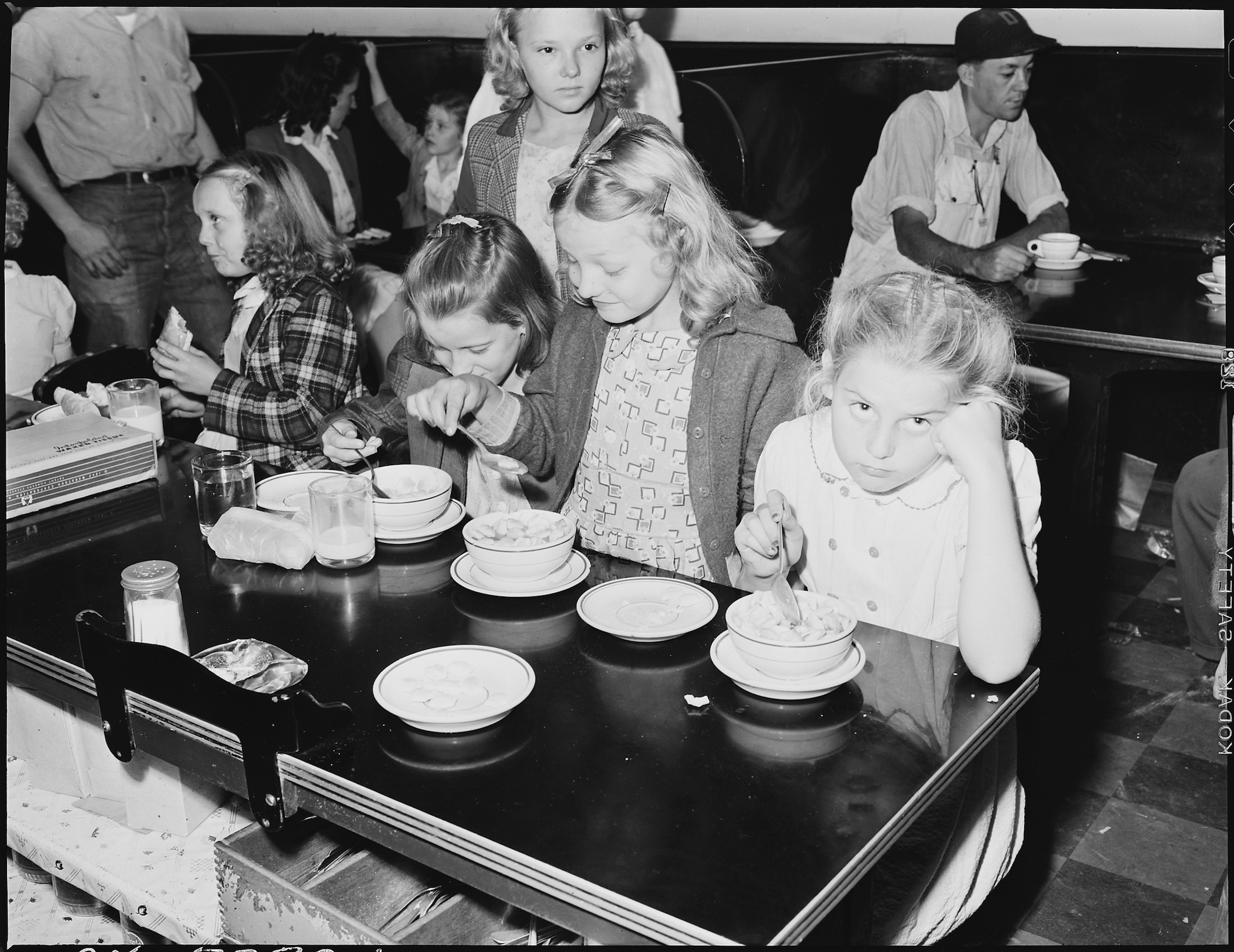

Hospitality is defined by host/guest relations. It’s also a practice that occurs in the private and social domains, which accounts for why so many punters get weird at cafés, restaurants and hotels. There’s something primal, something about how Mum and Dad did it, which unconsciously spills into the commercial domain. Much of the romance of food is generated by people with idealised versions of what their childhood meant in relation to their present. Their little version of the hospitality industry becomes Rosebud; a paid-for nostalgic rendering of what unconditional hospitality looks, tastes and smells like.

As children, if we’re lucky, we get served. It’s pretty much a one-way deal. Our parents (or carers) cook, clean, serve, nurture and encourage our bodies and self through our early years. They do so in the hope of hosting a person sufficiently able to care for themselves as adults. Sometimes, things don’t work out that way, and the adult-child stays home because it’s hard out there, and what makes it hard is doing the labour necessary to provision hospitality for oneself, let alone provide for a family.

Ironically, there are many people in hospitality who come from broken, dysfunctional homes. There is not so much nostalgia as resentment – and a yearning to forget. Churning out beautiful plates of food in an environment designed for pleasure becomes a consolation; a ‘this is how it should be done’ statement that seeks redress for the lack of nourishment they received as children.

If we don’t eat we die. Our bodies need energy to feed what biologists call the life-force – the force that ensures we never stop aging for a moment of our existence. That driving force, which compels our bodies through a quantum of lived experience requires energy to fuel it, and we fuel it by eating and drinking. Nutritionists settled on 8,700 kilojoules per day as the amount of energy our ceaselessly aging bodies require to go about our business. The kilojoule count is negotiable, which is lucky, but not by much if we aim to do anything other than obsess about how thin we are. Thankfully, we need less as we get older because life becomes more about decay than growth.

Reducing food intake to kilojoules and hospitality to host/guest relations is unromantic. Understanding the lawful minimum wage in Australia equates to $18.29 an hour (before tax) is hard-boiled fact, as is the reality that many restaurants and cafés don’t pay their workers penalty rates despite a surcharge for weekend and public holiday trading. When multinational companies like KFC have the front to tell the recent Senate Committee they haven’t paid weekend penalty rates for years and don’t aim to despite the law, it’s easy to understand why your local squat and gobble doesn’t either.

Valorising the production and consumption of food and hospitality practices has seen Australia develop a sophisticated, world-class hospitality industry. That’s a wonderful thing and worth celebrating. But the Victorian-era upstairs-downstairs relationship between workers and guests lingers in ways that should disrupt just a fraction of the multiple pleasures the industry provides us with.

So, next time you’re at your local, don’t be a weirdo, and spare a thought for the human beings on minimum wage, playing host.