It’s Monday morning and Sarah* storms into our shared office – she’s just been fined for the second time this year by rail guards on Sydney trains. While we’re sympathetic, and suitably ticked off on her behalf, no one is exactly surprised – almost all of us catch trains to work. Besides the $200 expense, Sarah’s bugbear is that the machines were all broken at Chatswood Station so she hadn’t had time to top up.

“I said to [the guard], ‘it’s not my bloody fault your f___g machines aren’t working,’” Sarah fumes to the crowd.

This sense of frustration and unfairness is being shared out more often than ever in offices all over Sydney. The advent of Opal means accessing public transport has never been simpler, with ‘tap on/tap off’ becoming a catchy lil’ mantra. But it comes at a more complicated price.

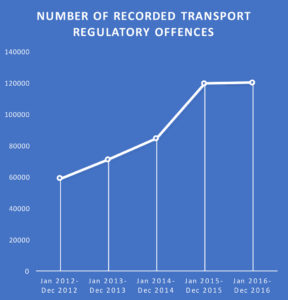

The recorded incidences of transport regulatory offences in the Sydney area have skyrocketed since 2014, leaving Sydney locals feeling like maximum resources are being put into catching offenders, and minimum into providing top-up facilities.

Number of transport regulatory offences

With the increased number of incidents, it can feel more and more like it’s simply a matter of waiting one’s turn to be fined for some accidental misdemeanour on a system you have to use for the commute.

Many Sydneysiders will have shuddered at the large queues to top up during peak hour at Wynyard Station. Armed with iPads, like school principals on the lookout for uniform slip-ups, guards wait on the other side of the boom gate. It’s not very extraordinary that the number of fines issued have gone up quite as much as they have.

According to the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR), the annual rate of transport offences in the Sydney local government area skyrocketed by a stunning 73 percent between 2015 and 2016. It should be noted that the umbrella of transport regulatory offences includes travelling without a ticket, but also other behaviour such as smoking, drinking or using offensive language on a train or on railway property.

The Opal system was introduced in December 2012. It wasn’t till December 2015 that most paper tickets were made unavailable. In July 2016 they were completely phased out to make way for Opal cards. During this period of transition to Opal, the number of recorded statewide incidences of transport regulatory offences rose significantly for three consecutive years: from 58,910 in 12 months prior to December 2012 to 119,324 in the year to December 2015, before levelling out at 120,068 the end of last year.

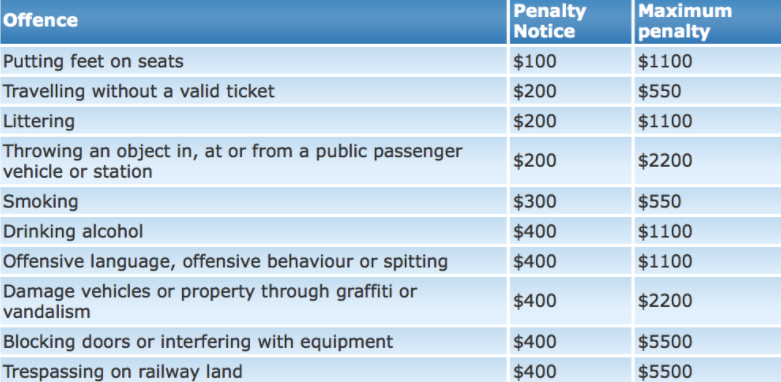

It’s hard to see how the offences (which result in painful fines between $100 and $500) are not due to this shift in system, adding financial stress to indicted commuters living in a city recently named the second most unaffordable in the world.

Kelly, a Sydney-based student, has been stung twice by $200 fines in the past two months while travelling by rail in the Inner City.

“One [fine] was for travelling on a child ticket because I left my concession Opal card at home,” she says. “The other was late at night running and tapping on at the disabled gates, and the delay between my friend before me meant my card didn’t register.”

Kelly says the thing that still troubled her most was that upon committing her second offence, the Sydney Trains Transit Officer repeatedly encouraged her not to appeal the fine. “[The officer] said I could try to appeal, however said it wasn’t likely to be successful as I had had a previous fine.”As a low-income student, Kelly is emotional and stressed about the incident. “[When he said that] I started crying and said I had just paid off another one.”

Unsurprisingly, no sympathy was shown by the guard, and the fine was issued.

Source: Sydney Trains

For Kelly and others, the problem doesn’t necessarily lie in the Opal system overall. The problem lies with the guards issuing penalty notices without any apparent discretion regarding the social or financial position of the accused, or their reasons for failing to tap on.

It’s true that the increase in transport incidences might not be due solely to the strictness of the fining parties. Kerryn Wilmot, a specialist in urban planning sustainability from the Institute for Sustainable Futures at UTS, thinks that the increase in transport regulation offences is due to the higher amount of people using public transport in Sydney.

Urban development is making the city denser, and the pressures on an overloaded public transport system are intensifying the experience for all commuters. As the system frays, the commuter pays.

Another factor is the strengthened ability of inspectors to catch offenders with the Opal system. Wilmot explains that, “[Previously] if I was travelling on a bus and going three sections and I only used a two-section ticket, there was no way for the inspectors to tell how far back up the line I got on the bus. Whereas under Opal they can see where I tapped on, or if I haven’t tapped on. So, it is easier to identify breaches.”

But it doesn’t take much in the way of observation to notice that there has also been an increase in patrol guards, and a decrease in ticket services. Many of us have squirmed nervously in our seats as we’ve seen Transit Officers patrolling down the carriage for the second time that day, or danced about waiting in a queue for that one (working) Opal top-up machine at Circular Quay. Effectively, the entire system for Sydney Trains has changed from a service approach featuring manned ticketing windows to a punitive system based on handing out fines on trains.

An underlying expectation that commuters are all able to top up online means that people who don’t – pensioners uncomfortable with online access, or students and unemployed who can’t afford the automatic top up – are particularly vulnerable in a public transport system they are the most likely to use. Nor is there much wriggle room for someone like Kelly, for whom the boom gates genuinely didn’t work. It nonetheless remains the commuter’s responsibility to verify a tap on, even as an exasperated tide pushes behind you at peak hour.

Residents of the Inner West and those working in the CBD are already especially prone to these fines due to the particularly high numbers commuting by train. As the amount of Opal users getting fined becomes normalised, a limited ability to top up at our major stations only makes it feel like the system is milking us for all we’ve got.

* Name changed.