It used to be a cake shop. In the years Before Gluten (BG), in the years Before Gentrification (B$), long before the median price for a Sydney home was $1 million, it used to serve the type of giant, triple-decker desserts and pastries that would’ve made the Country Women’s Association proud.

There was only type of bread (white), the type of Wonder Bread our ancestors fought and won two world wars with. Kids also ate the crusts because otherwise you’d grow up with curly hair. There was only type of sugar (also white). There was only one type of coffee (unknown). There were no avocados, smashed or otherwise.

And everything was packed with glutens.

Later, in a nod to the times, it started serving sandwiches and bacon-and-egg rolls along with cakes, scones, lamingtons and Chiko rolls. If you ordered a salad sandwich, it only came with lettuce (not “cos” – cos didn’t exist yet), onion and beetroot. No one wanted the beetroot, but it was reassuring to know it was there: just like the gherkin in the Big Mac.

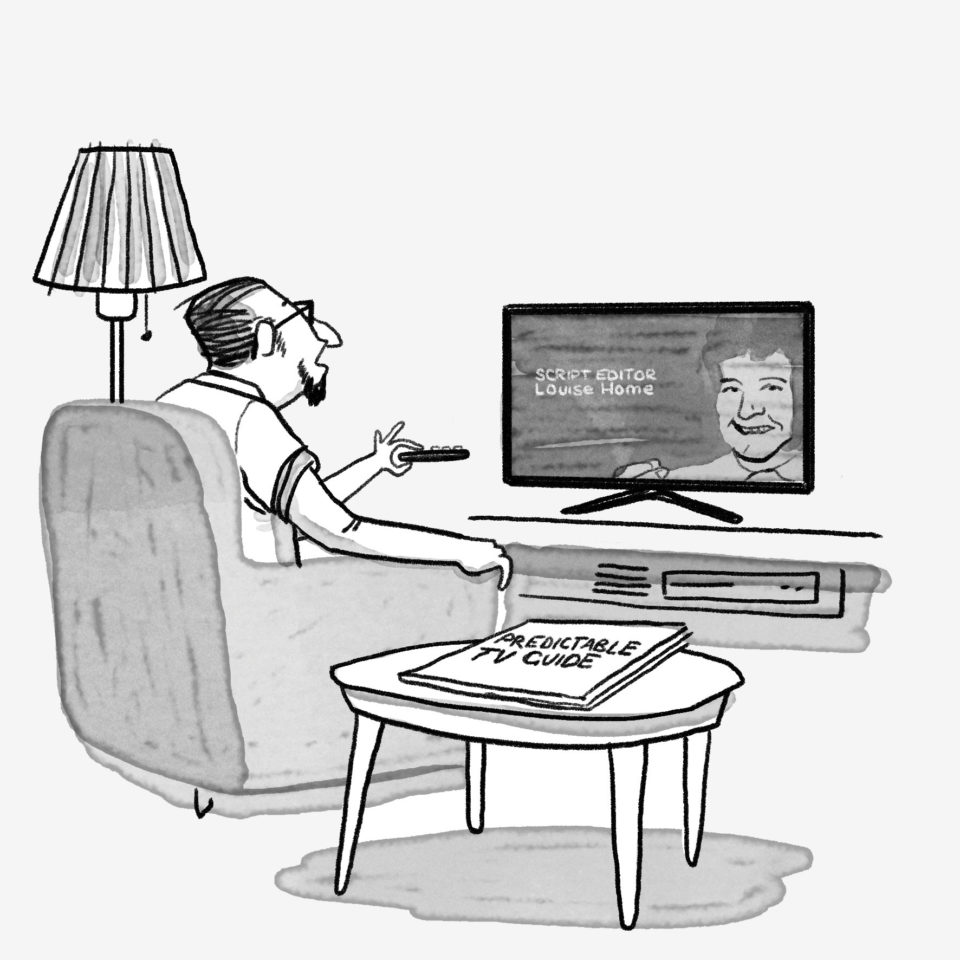

It was the sort of unpretentious place beloved by tradies and sparkies and labourers and mums with their kids. A locale harkening back to a simpler time before iPhones and property portfolios and MasterChef teaching five-year-olds to expect penne alla arrabbiata in their school lunchbox.

In short: it was a Café For Old Men.

It was the bottle of pink Himalayan salt that first alerted me to the irrevocable changes in my Old Man Café. It rested on a metal table that looked like it had been crafted out of the wing of a Boeing 787.

The menu was now partially in Italian and full of dishes I barely understood. For instance, the Caesar salad had become a “Contemporary Caesar Salad”, as if Caesar, former ruler of Rome and conqueror of Gaul, no longer cut it in a world where Asian slaw was served on cement slabs and watermelon juice came in mason jars. I imagined there was some kind of detector at the door that screamed if it detected anything with glutens in it.

The waitstaff were no longer tuck-shop types but young, hip people serving Bonsoy cappuccinos to equally young, hip people. The mothers with their kids now wore activewear and lived in million-dollar houses and drove 4WDs. The men were bearded, millennial and aspirational, one eye on their dining partners, the other on their iDevices. The well-behaved children nursing babyccinos were probably in Advanced Reading Classes and knew the difference between a tortoise and a turtle.

It was no longer a Café For Old Men.

I imagined all the tuck-shop-volunteer mums, the labourers in King Gees and checkshirts and even the roving pigeons and ibises all being bussed away to a less-salubrious suburbs to make way for the new customers.

This Old Man’s Café was heading the way of the Old Man’s Pub, a victim of urban gentrification. “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?” I muttered. But there was no longer anyone old enough – or interested enough – to understand what I was saying.