Why would any sane Australian go to the US for medical treatment?

For a brief tour of the US health system visit the popular crowdfunding site GoFundMe.com, where about 50 per cent of money raised pays off Americans’ medical debt: lung transplant, $80,000; brain tumor, $43,000; terminal cancer, $36,000. Medicare it is not.

But insanity didn’t drive Danielle Smith from Perth to Los Angeles for treatment. Desperation did. Despite the often farcical nature of the place, the one thing America seems clear-headed about is the path to legalising marijuana: 29 states have medical, 9 states, plus D.C., have gone the whole enchilada with recreational use. With 64 per cent of the population in favour, it’s practically the only thing Americans can agree on.

Pain creates its own compelling logic. Smith has a genetic connective-tissue disorder that triggers joint pain, musculoskeletal pain and neuropathic pain which constantly bothers her face, eyes and arm. Eight invasive spinal procedures – two without anaesthesia, to which she doesn’t respond normally – provided the 36-year-old art director no relief. Doctors resorted to opioids, anticonvulsants and antidepressants to contain her agony. Things got so bad, she Googled “assisted suicide in Scandinavia”.

A friend with an epileptic daughter told Smith about an oil from Colorado containing cannabidiol (CBD) that reduced the girl’s seizures from between 40 to 100 per day to zero.

Although Smith used to shun pot smokers at parties and bought anti-drug hype lock, stock, and barrel, she had nothing left to lose. Medicinal cannabis’s calming effects on Smith’s nerves is the sole effective treatment she’s found. When her supply of CBD oil abruptly ended, she moved to California. Only returning to Australia after a death in the family.

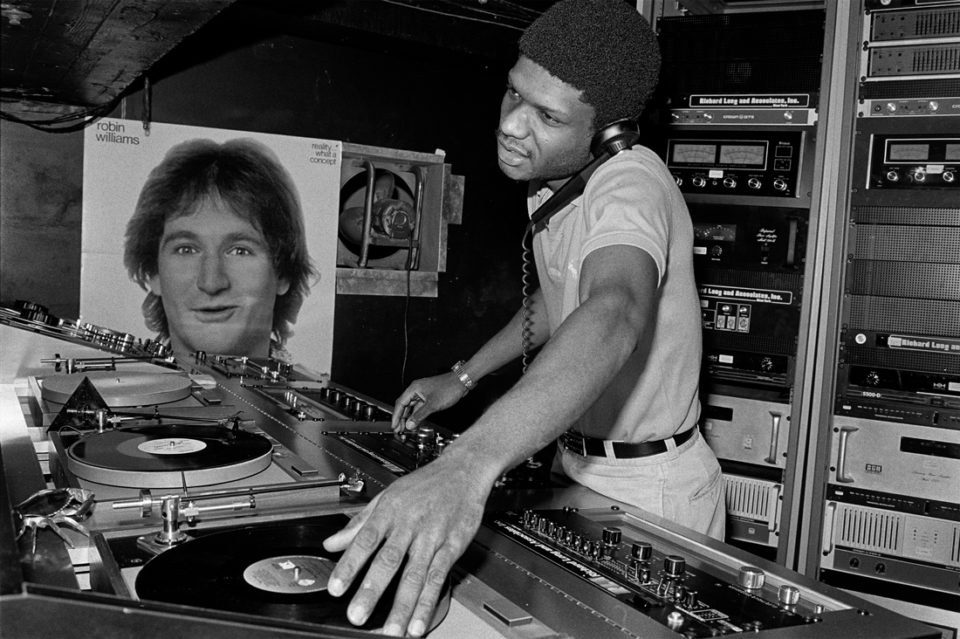

Now a passionate advocate for medical cannabis, Smith’s is wary of the way terminology is used to define and corrupt a more considered conversation by instead perpetuating old stereotypes and stigmas. “Please don’t use the word ‘marijuana’ in the article. It means ‘dirty tobacco’ and was used to demonize the Mexican population when Prohibition came in so has some dark racist connotations. We stick to using the word ‘cannabis’ only.”

Despite medical cannabis being legalised in Australia in 2016, it’s only been approved for about 600 patients and those lucky few face a byzantine maze characterised by Dr. Bastian Seidel of the Royal Australian College of GPs as “a complete basket case” with “huge barriers” to participation.

One barrier is cost. If, after waiting months for approval, Smith successfully petitions through her doctor for access, by her calculations, annual treatment will cost $25,000 in Australia versus $3,900 in California. How ridiculous for someone from a country with an enviable national health system and, well, no shortage of world-renowned weed! Enough of it that Federal Health minister, Greg Hunt, believes Australia could be the number one exporter of medical grade ganja.

On April 16, the Greens Party announced a plan to legalise cannabis in Australia: an unbridled upgrade from the current wonky medical mess to full-blown recreational use. Immediately, the media threw a coughing fit.

Clearing the disinformation smokescreen, the Greens are opting for something along Canadian lines, where the government acts as a single wholesaler and the goods are sold in plainly marked brown paper bags, as appetising as stale sausage rolls in an abandoned tuck shop. It’s hard to predict exactly how this will work out; although Canada is the world’s biggest supplier of cannabis, their recreational system won’t be in place until September. To glimpse the future, now, you have to go to California.

On a sunny Friday, I visited the MedMen dispensary in West Hollywood, “the Apple Store of Marijuana.” 4pm, the place was packed. At one of the big wooden tables with rows of iPads to navigate product descriptions, I grabbed a glass jar with a special lid containing a built-in magnifying glass and air vent to inspect buds. But “flower”, as it’s called, is no longer the point. Looking around, it feels like hardly anyone in California smokes. From the sheer variety of oils, edibles and even elegantly packaged suppositories, everyone is vaping, dabbing, nibbling or ingesting it in carefully curated doses some other way, it seems. It’s light years away from what the Aussie media know and understand and that’s why it’s a massive consumer industry now. I was a kid in a candy store until check out. You could practically hear the chorus of “legalise, regulate and tax” as the register chimed.

Can Australia go from zero to 60? Is it even desirable? California took 20 years to transition from medical to full-blown legal – and let’s not forget, federally, ‘marijuana’ is still a Schedule 1 drug in the US, up there with heroin and worse than cocaine, considered highly addictive with no medicinal value. In Australia, scheduling is more nuanced: THC is Schedule 8, a controlled drug, and CBD Schedule 4, available by prescription. If you could find a doctor who can prescribe, that is.

To get a sense of California’s journey from medical to legal, I talked with Carlos de la Torre, a founding member of California’s first research-based medical cannabis non-profit collective, Cornerstone. In 11 years, Cornerstone has morphed from a buyers’ club – cultivating, sharing, then selling to each other, in a closed loop of medically certified patients – to a store that will sell to anyone over 21 with valid ID. All thoroughly tested. Where most “street weed” can contain mold, metal, and pesticides, medical can’t, assures de la Torre.

Science has been at the heart of Cornerstone since its beginning, commencing with two PhDs, experts on the human endocannabinoid system, on its advisory board. De la Torre refers to his customers as “patients” without any trace of irony. Over the years, these patients have contributed their experiences to a database. In combination with Cornerstone’s research, overseen by its accredited Institutional Review Board, this provides users valuable insights into the complexities of treating ailments with the ever-expanding cornucopia of cannabis strains and derivative products. The fruit of this methodical approach is evident on Cornerstone’s website where a series of filters – variety; effects (e.g. analgesia, dissociation); greenhouse or sungrown – lead you to suitable strains, described in a poetic blend of wellness-speak and tasting notes: “Mood-lifting and potent full-body relaxation. Wonderful sweet aroma of vanilla cream, cherry and coconut.”

“Since full legalisation, sales are up 40-50 per cent, maybe more. The gold rush is happening.” De la Torre maintains that recreational users come bundled with medical complaints, too. “Stress relief, anxiety, pain management are the big ones.” While business may be booming – LA has something like 185 legal dispensaries and in West Hollywood on-premises licences are in the works – it’s not without complications. The main being the federal Schedule 1 status. “Counter-intuitive and hypocritical, even on their own terms,” vents de la Torre. Practically, it means the Feds treat any use of the banking system as money laundering. “People have figured out how to circumvent that with management companies, but for the most part the big dispensaries are cash businesses.”

There are security issues of dealing with massive quantities of cash, not to mention the hassle of paying everything from rent to employees with paper, and the IRS applies its own set of screws, too. But these nuisances are a minor headache. “No one in California is all that worried, evidenced by the billions of dollars of institution money that’s pouring in.” De la Torre is on the cusp of an incredible transition. “We have a window of five years. Then big companies will have rolled up the small.”

Australia is a littler pond but perhaps with even bigger sharks. As the government puts its toe in the water, loosening regulations around exports, the Cann Group, the country’s first recipient of licences to research and cultivate medical cannabis has seen its stock rise 400 per cent over the past year. Investors such as Ellerston Capital (25 per cent owned by James Packer) may have already made significant profits. Global giants like Canada’s Aurora Cannabis, which owns 22.9 per cent, is sniffing around, according to Australian Financial Review, ready to chomp down the remainder. If you harbour any quaint dreams about a hippie-led commercial cannabis carnival, you should put them in your pipe and smoke them.

If Australia is to learn anything from the US it’s that although states’ rights have been instrumental to progress, resolution requires federal action. And for people like Smith, the sooner cannabis is a health issue rather than a criminal one, the better. But the image problem the drug has doesn’t fit our western dualistic thinking. How can something be both good for you and fun at the same time? We can’t imagine a medicine that doesn’t require a spoonful of sugar to make it palatable.

But at the deepest level, western drug policies have little to do with medicine. Historically, they are about race. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, opium became restricted due to its association with Chinese immigrants. Hypocritically, opium consumption was forced on China by British and American “gunboat diplomacy” during the Opium Wars. In the US, cocaine became associated with Blacks and marijuana with Mexicans; drug use in general as a threat to White morality, hence superiority. And there’s still a stigma.

Leveraging the League of Nations, the US anti-narcotics position became de facto global policy. Now, the self-inflicted wound of the pharmaceutically-induced opioid epidemic’s culling of the White population has brought things to a head. Cannabis is increasingly viewed as a salve, even in traditionally red states like Kentucky and Indiana.

Smith chose to go to California not Colorado in part because she preferred sunshine over snow. But in her six months there she rarely got to enjoy it. Weaning herself off prescription drugs pregabalin, then buprenorphine, then duloxetine put her through serial cold turkey – an experience that even as a habitué of unpleasant sensation she found overwhelming.

“If the only side of effect of cannabis is a slight high,” she mused, “I can live with that.” If the national side effects of legalisation are more tax revenue—up to $1.8 billion according to the Greens—for infrastructure, schools and healthcare, a boost to agriculture, plus fewer people in jail, perhaps we can all live with that, too.