Would you rather be a criminal, a slave, or a refugee? Criminals, writes Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism, are an “exception provided for by the law” – that is, society has rules about treating criminals fairly and respectfully. Slaves, meanwhile, are “needed, used, and exploited, and this [keeps] them within the pale of humanity.” But refugees have neither protection nor a function, according to Arendt, and as such are outside the protection of law and society: “the scum of the earth.”

Arendt wrote Origins in the aftermath of World War Two, and the book was published in 1951. That same year the United Nations adopted the Refugee Convention at a conference in Geneva. Among other things, the 1951 Refugee Convention provided a universal definition of a refugee; it was the first global effort to bring refugees within “the pale of the law”. Australia has a proud place in this history – the Convention required so many signatures before it entered into force, and ours was the signature that brought it over the line.

In a continuation of this tradition, two Australians – Professor Jane McAdam and lawyer Daniel Webb – have in the past month been internationally recognised for their work in refugee advocacy and law.

McAdam, Scientia Professor of Law and Director of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW, was awarded the prestigious Calouste Gulbenkian Prize on July 21st. The award recognises the impact of her work on Australian policy and on the lives of thousands of refugees globally; in particular with her work in creating legal frameworks for people displaced by the effects of climate change.

“A number of countries,” McAdam said, “particularly Bangladesh, but also small island states in the South Pacific, started asking ‘well, what if our people need to move because of the impacts of climate change?’ And what became pretty striking was that there were gaps in international law.” McAdam explained that the established definition of a refugee – someone with a well-founded fear of persecution on account of their identity – left open the question of whether those displaced by climate change would be protected.

McAdam, as an advisor and legal architect of a program called the Nansen Initiative, helped to fill some of those gaps. During its work, the Initiative also found that “there’s a lot that governments can do right now that can have really lasting and meaningful impacts on whether or not people are forced to move, and if they are, for how long.”

One measure McAdam mentioned was an Australian government program undertaken with the island nation of Kiribati. The pilot scheme, McAdam said, allowed around thirty Kiribatians to train as nurses in Australian universities, with the choice at the end of their degree of applying to work in Australia or taking their skills as nurses back home. Both governments saw the scheme as a “win-win situation”, according to McAdam. “And what’s interesting in that in the last six months there have been reports by the World Bank, the Lowy Institute, and the Menzies Centre, all of which have advocated for enhanced labour migration from the Pacific to Australia, which is interesting because, politically, they’ve got quite different bents.”

“What they show is that if you allow people to move more freely, you would – in terms of the foreign aid budget – you would just exceed what we’re providing in aid so much more and at the same time build up skills and capacity.”

Earlier this year, McAdam also co-authored a paper advising the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on the strategies it should implement in cases of displacement caused by climate change and disaster.

President of the Portuguese Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa making a speech. Photography by Márcia Lessa

Closer to home, Daniel Webb, a lawyer with the Human Rights Law Centre, has been announced as a finalist for the 2017 Global Pluralism Award. Three winners will be announced in November at a ceremony in Ottawa, Canada.

The accolade recognises Webb’s work in domestic advocacy, including his role in the #LetThemStay campaign. That campaign pressured the Australian government to allow 267 refugees – many whom were brought to the Australian mainland for medical treatment – to remain in Australia. As a result of the campaign, almost 150 of the refugees were released into community detention in Australia rather than being returned to detention offshore.

Webb cites this campaign as a moment “when the public’s thinking was about people, and they took a stand – they told the government that there are lines of human treatment that you can’t cross.” Webb has been outspoken against the government’s refugee policy, including what he calls the “warehousing” of refugees and asylum seekers on Manus and Nauru and legal sanctions that limit public reporting on the detention centres. “Ultimately the government says that the ends justify the means, but that’s our judgement to make – that is the Australian people’s judgement to make, and we can only make it on full information, and there’s so much information that we don’t see.”

Daniel Webb

When asked if his own broad knowledge of the issue and its complexity could sometimes be disheartening, Webb responded that “the morals of what we’re doing right now are really simple… painfully simple, actually.” The nature of government, he argued, was that “you have to deal with complex things every now and again, but you have to do so within certain parameters, and one of those parameters is you’re never cruel.”

Both Webb and McAdam recognise that the refugee debate in Australia has come to a standstill. Webb stated that “for so long in Australia it’s been bipartisan policy to be deliberately cruel to innocent people who come here and seek safety, and there’s a tendency at times to think that that’s normal. But what being shortlisted for this award recognises is that the rest of the world doesn’t see it that way.”

“This kind of international recognition is a real wake-up call for people in Australia that we have, on this issue, strayed a long way from our moral compass.”

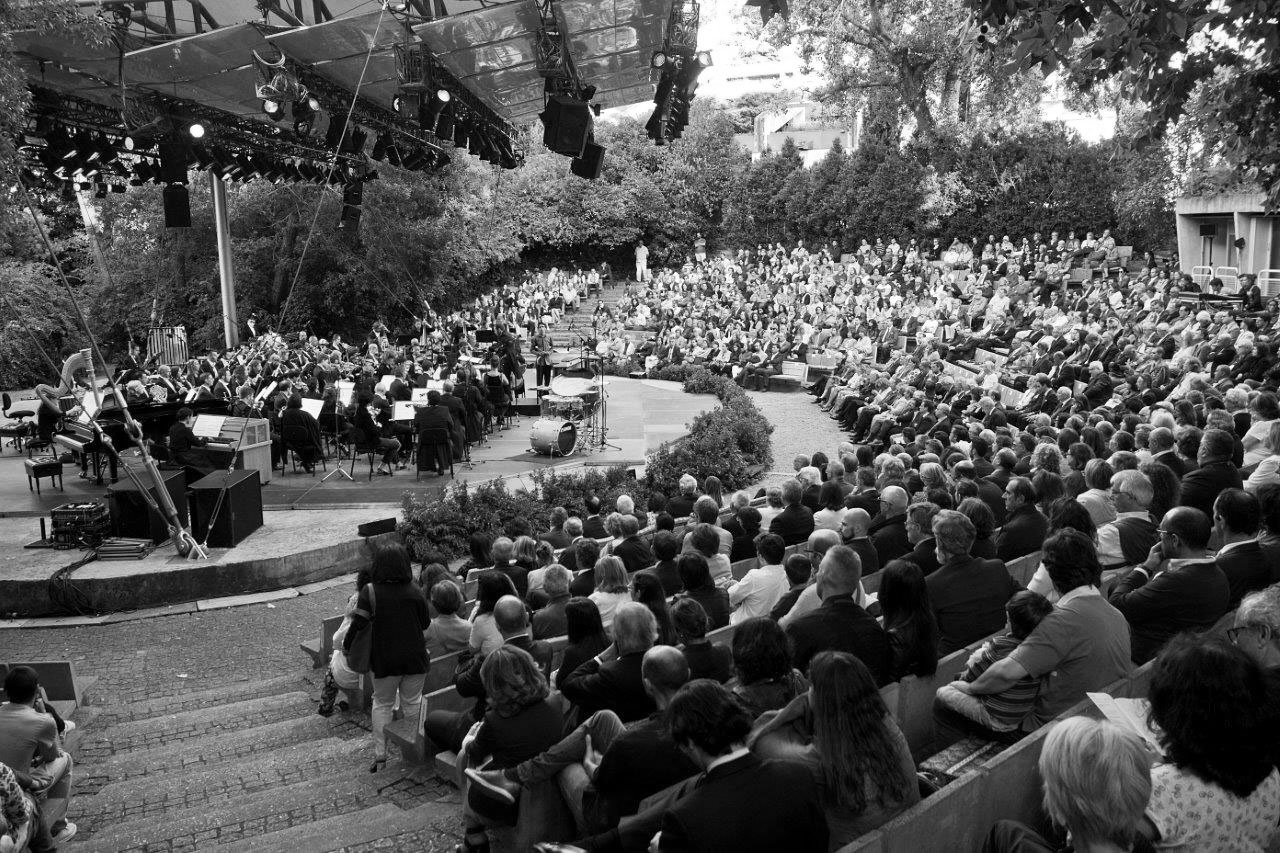

McAdam, when discussing the political gridlock, told NEIGHBOURHOOD about a debate she participated in at Sydney Town Hall in June of this year. The topic was that the Refugee Convention was out of date, and she was on the negative. McAdam faced an uphill battle: a poll taken at the beginning of the night measured 35% who thought the Refugee Convention was outmoded, and 44% undecided. By the end of the night the majority was on McAdam’s side – 71% agreed that the Refugee Convention was still relevant.

“I think that just having the opportunity and the time – which we had over the course of an hour – is vastly different from these three-second media grabs you get. It’s very easy to say something in a three-word slogan; it’s a lot harder to explain the complexity of forced migration in three words.”

In a statement released after winning the Calouste Gulbenkian Prize, McAdam reiterated the global refugee statistics: there are 65 million people displaced due to conflict, and 25 million displaced by disasters and climate change. In light of these statistics, Australia’s domestic refugee debate can feel disconnected from the international reality.

“The debate in Australia has become so inward looking and parochial, and yet if you look at Australia internationally we do have something more positive to say. It’s just that that doesn’t cut through so much in Australia because that’s not where the politicians are at – it’s all about the votes, and about the borders, security,” said McAdam.

“We need to lift our eyes a little bit more.”

The Opera House is hosting ‘Breaking the Deadlock’, a panel discussion on approaches to Australia’s refugee policies, featuring Gillian Triggs, Paris Aristotle, Guy S. Goodwin Gill and former refugee Huy Truong. Presented by the Kaldor Centre and the UNSW Grand Challenge on Refugees & Migrants. August 15, 6:30pm.