When I say ‘my’ King’s Cross, I don’t wish to give the impression that I ever owned King’s Cross or even felt that it belonged to me after a couple of drinks on a Saturday. I mean ‘my’ in a sense of time and not of property. The time I mean was my (and the century’s) twenties, which is the right age for appreciating indigestible food, dubious drinks, prehensile women, exhausting conversation, hair-raising gymnastics and about two hours’ sleep a night. At this time, however, I considered the food and drink as exciting as the conversation and I could still bounce like a golf ball after walking five or six miles and sleeping two hours.

Today my King’s Cross is somebody else’s King’s Cross. It seems to have vanished utterly. So, of course, has my youth, and it seems only fair to take into account the possibility that one depended on the other. There are stills swarms of young human beings eating, drinking, talking and making love in what passes for King’s Cross today, and no doubt they are enjoying it as intensely as I did. But, looking at it from the aguish plateau of my (and the century’s) sixties, the place just doesn’t seem the same.

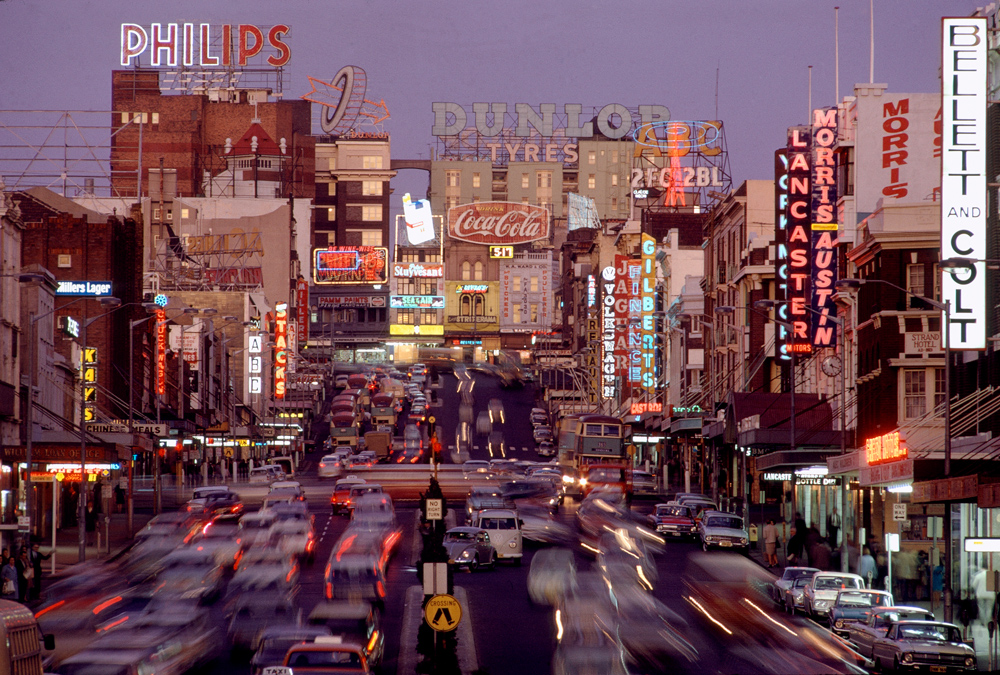

I don’t know whether my King’s Cross was any better than today’s – or any worse. For, whatever happens to its landscape, King’s Cross will always be a tract apart from the rest of Sydney, still contemptuous of the rules, still defiantly unlike any other part of any other city in Australia. And, though its skyline keeps on changing in an unpredictable and bewildering way, its essence of individuality does not change, its flavour, noises, sights and smells remain the same immutably. For this reason I find as much pleasure in contemplating it today as I did when I looked out of a Woolcott Street window in 1922 – indeed, with its unending flux of lights and colours, its gaudiness and reticence, its sunsets and midnights, it seems (to me) a good deal more beautiful than the highly advertised stones and sand of Central Australia. To me, the Chevron Hilton hotel, with its glittering windows and huge verticals, is as awe-striking as Ayers Rock.

Where is King’s Cross, or what is it? Literally, I suppose, the Cross is where the five streets cross at the top of William Street. But, in the geography of the post office, letters addressed to King’s Cross may go to Darlinghurst, Elizabeth Bay, Potts Point, Woolloomooloo or even the fringes of Rushcutters Bay. It is a term rather than a place. Its boundaries are flexible. People who ‘go to the Cross’ or ‘live at the Cross’ may mean anywhere from Taylor Square to Wylde Street. This doesn’t matter. They are expressing a state of mind, just as the Cross itself is perpetually expressing a state of mind.

With the exception of some vexing intervals in places like Melbourne, Bugbug, Port Tewfik and Tidworth (Wilts.), I have lived in or on the margin of King’s Cross for more than forty years. The Harbour has never been out of my window. During that time I have watched hundreds of houses decay and vanish, streets change their names as well as their geometry, rows of buildings topple and become holes in the ground, and other buildings rise almost instantly like the mango-trees of Oriental conjurers. I have seen the swishing trolley-buses come and go and I have watched horses change to station-wagons. I have watched the pushes give way to the bodgies and the bodgies to the hippies (or whatever is the newest name for flash young men in search of adventure). I have watched the old William Street eating-places (21 meal-tickets for £1) turn into bistros, niteries, wine-and-dine cafés, steak houses, spaghetti-bars and espresso lounges.

Through all these transformation-scenes, the Cross has managed to cling defiantly to the tatters of its unconformity. Its streets today are just as crowded with eccentric, extroverted or fantastic people, but instead of the ripe Australia idiom of the C.J. Dennis period most of them issue torrents of Italian, Hungarian, Slavic, Dutch and German and Greek. The skysigns still blossom as brilliantly as ever in the electric gardens overhead, but their alphabets are fluorescent now where they used to be spelt out with clusters of naked globes. The buildings are higher, straighter, airier, lighter and more antiseptic, but the extraordinary old contrast between mansion and slum (a grimy two-floor tenement huddled next to a tower of ‘luxury’ apartments) has practically gone.

In spite of its vestigial flamboyance, for all the survivals of its native sauciness, King’s Cross is not the King’s Cross I remember from the ’20s and ’30s. Its people, certainly, are noisy, irreverent, crackpot and emotional, but they are not the kind of people who used to charm and horrify and puzzle me when I lived in Old Hampton Court. Where have they gone? Where has my digestion gone? Where has my hair gone?

Last week I dug up an old book of jingles which I wrote about ‘Darlinghurst’ over 30 years ago. In those days, Darlinghurst meant nothing but King’s Cross –

Where the stars are lit by Neon,

Where the fried potato fumes,

And the ghost of Mr Villon

Still inhabits single rooms,

And the girls lean out from heaven

Over lightwells, thumping mops,

When the gent in 57

Cooks his pound of mutton chops…

and also:

Where the Black Marias clatter

And peculiar ladies nod,

And the flats are rather flatter

And the lodgers rather odd,

Where the night is full of dangers

And the darkness full of fear,

And eleven hundred strangers

Live on aspirin and beer.

The fried potato has given way to deep freeze or instant food, all mutton has become ‘lamb’ (just as all fowls have become ‘chicken’), the Black Maria seems to have disappeared with its nickname, and the 1100 strangers living on aspirin and beer have proliferated into 11,000 strangers living on aspirin and beer and also smoked eel, metwurst, goulash, salami, Vienna schnitzels, Benzedrine and tranquillizers.

No doubt the strangers and lodgers are still odd enough, but they no longer charm or horrify me. Nor – possibly because I have since acquired fixed ideas about the hours at which I rise or retire – do I seem to see, as I used to, unshaven gentlemen in boiled shirts and the remains of black ties tottering about at 7 a.m. as if the daylight hurt their eyes. Nor do I see blondes in nightgowns or pyjamas clip-clopping in and out of delicatessen shops at high noon, a spectacle which aroused little or no comment in the 1930s.

As for the food, it has been said that the postwar influx of Europeans has widened our taste and improved our cooking. This strikes me as boloney in the full sense of the Bologna sausage. It is true that King’s Cross is crowded today with restaurants and cafés of a dozen nationalities – Dutch, Hungarian, German, Russian, Indian, Italian, Swedish, Indonesian and others – but this is no evidence of better food. Since the only two great cuisines of the world are French and Chinese, both of which flourished superbly in Sydney before the war, the new tides of Slavs and Balts and middle or southern Europeans have merely imposed the exigencies of their sparse national larders on the Australian menu. They have contributed a number of sausages as well as a number of ways of disguising veal. But anybody who believes they have improved Australian eating is clearly ignorant of the state of Sydney’s restaurants in the first quarter of the century. The claim is preposterous to anyone who remembers the glories of Monsieur Lievain’s Paris House, Stewart Dawson’s Ambassadors, the first Romano’s, Pearson’s fish-café and Watson’s Paragon, the Cavalier in King Street, the Cafe Francais in George Street, Petty’s Hotel and a dozen more dining-rooms, all now vanished. I find little compensation today in walking through King’s Cross and looking at the spaghetti-bars, the hamburger-counters and the lines of electrically ‘barbecued’ chickens rotating in their glass coffins.

Perhaps something a little too calculating, a little too prudent, a little too commercial has corroded the joie de vivre. There were few inhibitions of cost, respectability or the need for publicity in the King’s Cross I remember. I never saw the spirit of the Cross more charmingly demonstrated than one night before the war when I was living in a balcony-flat directly over the waters of Elizabeth Bay. I had come home late from the theatre and stepped on to the balcony to enjoy the silence of the Harbour, glittering with reflected lights. Suddenly I became aware of a regular plopping noise, followed by soft thuds and hisses. Gazing up, I was delighted to find that someone on a balcony above me was engaged in sailing large white dinner-plates into the moonlit air. They soared out into the night, glimmered for a moment and splashed into the water below. But what was the hissing noise? Peering farther up, I was even more delighted to observe that someone on another balcony was taking advantage of these targets from Heaven by firing an airgun at them.

Perhaps there was some of the same spirit in the disc-smashing parties which were popular in the ’30s, before long-playing and almost indestructible records were invented. The host would provide piles of old played-out records, those which bored him most, and the guests would shatter them over each other’s heads until they were ankle-deep in vulcanite. I recall, too, a ‘house cooling’ party, given the day before the entire apartment-building was due to be demolished, at which the guests were invited to lend a hand by sawing doors in halves, pulling up wainscoting and ripping the wallpaper down in strips.

Perhaps, indeed, the inhabitants of King’s Cross have changed in 30 years. At any time I can shut my eyes and see them again – ‘Hop Harry’, the amiable retired welterweight who became an ‘interior decorator’ (i.e. bootlegger); Chris Brennan shambling to his lonely bed-sitting-room in Rockwall Crescent; Bea Miles, then like Lil Abner’s girl, shapely and brown in shorts far ahead of their time; Arthur Allen, the rich solicitor, floating past in his transparent electric buggy; Mary Gilmore gazing out from her flat in Darlinghurst Road; Will Dalley, delicately wheeling a game-pie home in a borrowed perambulator; Hector Bolitho, the Royal biographer, darting along Macleay Street in lavender gloves and a bowler hat; ‘Bad Bill’ Quinn, self-appointed guide to the underworld; Dulcie Deamer, inextinguishably vivacious in a leopardskin after the Artists’ Ball; Geoffrey Cumine with his blue beret, pea-green shirt and brass ear-rings and a butterfly tattooed on his face; Driff, the black and white artist who hired a taxi-driver to take his old white cockatoo for a ride around Centennial Park – hundreds more in the procession.

But even the streets have altered. Woolcott Street has become respectable and changed its name to King’s Cross Road. The old mansions have been pulled down. William Street itself, with its broad double lanes and flowery centrepiece, has been transformed completely since the days when I walked its length coming back from the Stadium. Then it was less than half its present width, a narrow and somewhat sinister street lined on one side with frowsy terraces and dimly-lit shops. It was the original ‘Dirty Half-Mile’, a title afterwards transferred to Woolcott Street and now without a claimant.

This was my King’s Cross. Whether it was any better or worse than today’s King’s Cross I wouldn’t know. But I loved every inch of it.

‘My Kings Cross’ by Kenneth Slessor. Extracted from Bread and Wine: Selected Prose (Angus and Robertson, 1970). Reprinted by kind permission of Paul Slessor.