I appeared to be standing in the midst of a mass grave. The endless rows of cold, grey, concrete steles resemble a procession of coffins waiting to be tucked under their national flags. It was winter, and the melting snow left tear streaks down the sides of their faces. Some stood defiantly upright like sentries awaiting orders; others seem to have succumbed to their fate of being swallowed by the earth. The effect was like a grim optical illusion, a misshapenly manicured forest of dominos waiting for the final push.

Walking between them is a test of claustrophobic endurance. The space between each block only permits the passage of one person. My arms grazed against each slab and I resisted the urge to utter a self-conscious ‘Excuse me,’ as if I was intruding upon their grief. The path beneath undulates in cobblestoned waves; my feet catch and trip with each step, as if the dead were reaching up to grasp at my ankles. I hasten my pace, afraid of being buried under the weight of their silenced stories.

In many ways, Berlin is a haunted city, the remnants of World War II still within an uneasy reach. It seemed fitting that my inaugural solo adventure would end here, at Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. The architectural monument occupies 19,000 square meters at the heart of the city and offers an underground museum that houses the identities of those belonging to the unmarked field of sarcophagi.

Its conflation of horror and serenity uncannily mirrors the emotional tenor of my three-week trip through Central Europe. As I joined the throngs of visitors waiting to descend into the bowels of Germany’s painful history, I returned to a query that was sparked on the first day of my trip: is it possible to heal through art?

Hampered by inclement weather on day one of my European escapade, I was forced to take refuge in the cavernous chambers of Munich’s Kunstareal museum quarter; its trio of Pinakotheken art galleries commemorates masterpieces dating back to the fourteenth century.

Confession: I know nothing about art.

This unexpected detour elicited the memory of a poignant scene from Sam Mendes’ Skyfall that comments on the rare ability of art to mirror life’s profound truths. As James Bond sits pensively in front J. M. W. Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, his quartermaster draws a parallel between Bond’s growing irrelevance in a new age of cyber terrorism and the remains of the old war ship being discarded to a shipyard. The quartermaster, a decidedly younger challenger to Bond’s embodiment of old world values, asks him what he sees, to which Bond replies, “A bloody big ship.”

Have museums also become quaint relics of the past, waiting to be replaced by a brave new world of technology?

Stepping into the venerated halls of the Neue Pinakotheken, one of the world’s most esteemed galleries for European art, the sound of the unrelenting rain gave way to a reverential hush. The rooms stretched towards the ceiling in rich hues of reds, greens, and blues, each series of chambers painted a different color as if denoting the chapters of a novel.

The walls told stories of unrequited love, epic battles, mythical creatures, and mischievous deities. It was like entering the pages of a timeworn picture book. Even the occupants of the museum seemed to be from a different era. Elderly patrons sat in miniature armchairs quietly contemplating their favorite portraits, children lay on leather benches taking in the unfamiliar silence, and groups of visitors huddled eagerly around museum guides as if listening to a campfire story.

I stopped behind an elderly woman who had been sitting in front of a rare portrait from Van Gogh’s Sunflowers series for the past hour. I wondered if she saw something that I didn’t, there was only so much space on the canvas. I asked her why she liked this particular piece so much; reluctantly, she shifted her eyes away from the aged brush strokes and replied, “Well, we all know what the painting looks like right? But we come here to experience it.” When I turned to leave at closing time, she was still standing watch over her sunflowers.

Emerging from this cocoon of art and legends was like falling through a trap door. Reality hurtled forward to greet me, dispersing the dreamlike fog that had blanketed the day. Walking back along the streets of Munich, it was hard to miss the scattered marks of a modern world in turmoil. Newspaper stands blared headlines of terror, death, and scandal, a pair of severed angel wings was sprayed in crimson across the grey canvas of a construction site, while clusters of candles dotted the shadowed corners between buildings to form miniature tributes from strangers to other fallen strangers. It was a different kind of art; an art in mourning that transcribed the scars of our present day traumas.

In an effort to shake the ominous cloud of uncertainty that had fallen over the world, I found myself inexorably pulled towards unlikely spaces for consolation: art galleries and museums.

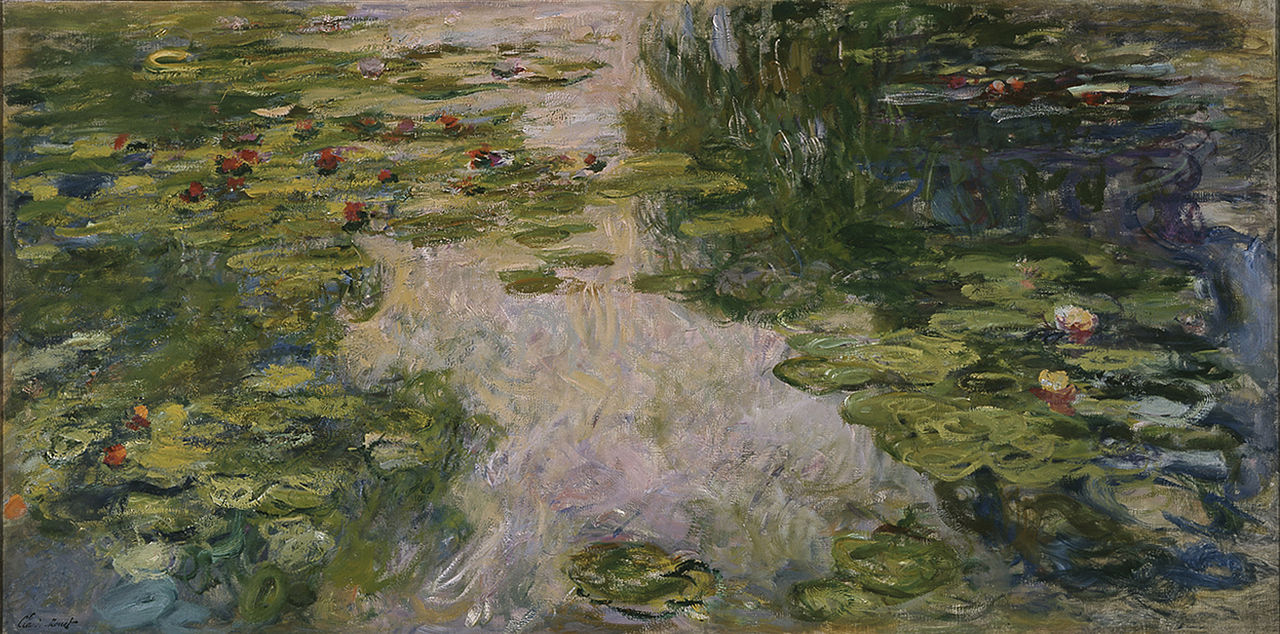

I spent a day in the company of Monet’s water lilies at Zurich’s Kunsthaus Museum for Modern Art, and another two roaming the ballrooms of Vienna’s Belvedere Palace, circling back several times to gaze at Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss. I encountered a lost boy in front of Pieter Brueghel’s Tower of Babel at Vienna’s Kunsthistorishes Museum, and reunited him with his parents below Antonio Canova’s sculpture of Theseus and the Centaur. Beneath the Ishtar Gate at Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, I learned that German security guards were skilled at reprimanding unruly tourists in four different languages. The nostalgia of these historical spaces became my refuge from the confusion of the present; each novel experience within their walls was accompanied by a wistful tale or work of art from the past, allowing me to hold hands with the rest of the world through shared memory.

There is a reassuring sense of escapism and imagined community when one turns to cultural institutions during times of crisis and trauma. We carry our respective emotional baggage into these artistic shelters for personal and communal reflection, finding comfort in the lessons embedded within myths and fables of bygone eras. New memories and impressions are formed through our engagement with the past.

Richard Wendorf, the Director of the American Museum in Britain, denoted museums as “the chapels and cathedrals of an increasingly secularized society.” They serve as intimate public spaces, where artifacts of cultural difference and stories of diversity are memorialized rather than shunned. In a rapidly shifting social landscape, the relevancy and purpose of art and museums lies in their ability to tell stories that are ennobling. In times of need, they provide us with a liminal space for collective healing.

Still waiting in line at Berlin’s memorial, I glance back towards the concrete forest. Dotted amongst the grey now were splashes of red, pink, blue, and green, as if someone had flicked a wet paintbrush onto the stark canvas. Children dressed in their festive winter armors were running gleefully between the steles, eager to lose themselves among the shadows. Some played hide and seek beneath the towering blocks, giggling as if one of their Lego creations had sprung to life. Others used the recessed slabs as stepping-stones. Mothers pushed their baby strollers along the narrow channels, their tiny occupants occasionally letting out squeals of delight as the ground rose and fell like a rollercoaster. In the distance, a couple sat huddled on the tallest block above them all, their bodies blurring into the amber glow of the setting sun.

Perhaps, this is what it means to heal. Through the marriage of terror and art, a new world order is forged where beauty and horror can coexist.

The uneven stone path I had previously tripped across no longer resembled a minefield of ghosts, but appeared to echo the stories of redemption embroidered into the pavements across Germany in brass Stolpersteine ‘Stumbling Stones.’ Families torn apart by war are ultimately reunited through art, their lives given symbolic closure and the chance to heal in front of the homes where they were most damaged.

I turn back towards the museum guide waiting to lead us in and asked her what the architect of the memorial intended for it all to mean. She smiled at me knowingly and after a brief pause replied, “Whatever you need it to mean.”

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe covered in snow, February 2009. Photo credit: Chumchum14, Creative Commons Wikipedia