The other day when I was going for a walk in the park I met a horse called Horse. It was in the Darrell Jackson Gardens in Summer Hill: a tree-encircled oval where, in summer, cream-clad little boys play cricket and where, in winter, there is refuge for the homeless among us. More pony than horse, Horse is sometimes to be seen trotting around the perimeter of the grassy area of the oval. His owner, a gent in his seventies, holds a rein in one hand and steers his bicycle with the other as he rides alongside the grey pony on the asphalt path which runs around inside that ring of trees. This day, however, a Sunday, the old fellow was showing him off to a crowd of picnickers.

I stopped to listen: a tale of sustained harassment by neighbours, which left both man and horse nervously exhausted. Fortunately this was all in the past now and things were on the mend. That perdurable Australian optimism: everything was coming up roses again. In a pause of his recitation, I asked the pony’s name. “He’s called Horse.” While this was going on Horse was extruding a thick pink penis so long its blunt tip threatened to brush against the dying grass of the oval down below. The kids were wide-eyed but none of the adults remarked upon it. What could we have said?

I remember Horse from my earliest days of coming to live in Summer Hill, towards the end of 2004. He used to trot down my street sometimes, usually in the dusky afterglow of a Sunday evening; and seemed to carry with him a breath of the air of another time, before the one we are living in now. There were other reminders: the tatty shop selling military memorabilia; the depot where goods donated to a church charity were sorted and, sometimes, sold; the second hand store where Peter the Russian, son of a Green Cab driver, always imagined he’d found a lost masterpiece amongst the junk art he displayed along with the furniture and the bric-a-brac. All these places have gone now, replaced by cafes, bars, hair-dressing salons, gift shops, manicure and pedicure clinics; yet the older village they comprised somehow persists, not in the built environment and not in the commercial enterprises that inhabit it; but in the actual people who still live around here.

Let me introduce you to a few of them. Every now and then I’ll hear a shuffling sound in the street outside and I’ll know that’s Cosmo, in his slippers, going down to the village for something or other. Cosmo is a Greek from Russia who used to win competitions for Cossack dancing in the 1950s and 1960s. With the prize money from one of these he bought a big green Rambler Classic, which he often parked outside my building. Cosmo used to run the motor for half an hour or so every few days but he hardly ever drove it anywhere and in the end (rust) he had to let it go. He loved that car but isn’t a man to nurture regrets. Beautiful, he says. Beautiful country, beautiful day. I sometimes wonder if the tiny shuffling steps he takes are a legacy of the Cossack dancing but I won’t ever ask him that because it’s really not my business. I know he contemplates his own mortality on a daily basis but his reaction is always the same: he extols his luck.

Kevin I call “the transistor radio man”. I don’t know where he lives but most days he will be parked in his wheelchair outside the supermarket, or perhaps the newsagent, with a colourful shirt on, shiny black shoes and a radio in his lap blaring out music. Some commercial station that plays pop tunes; it’s hard to tell which one because Kevin’s radio isn’t reliably tuned to the frequency so there’s usually quite a bit of static. He’ll have his baseball cap, upside down, on the pavement in front of him, weighted with a couple of batteries. Or else a plastic top hat. He never asks for money but you’ll get a toothless grin if you drop a coin into the hat. If you ask him how he is, however, his face will cloud over and he will shake his head: not good; but really, I think he is a contented soul, or as contented as a man begging in a wheelchair can be.

The other day I saw Kevin deep in conversation with Doug from Dubbo, who is a recent arrival in these parts. Doug lives up the road in a room in a boarding house and is usually to be found sitting, in his green oilskin jacket, on the bench outside the chemist or the bank, upright, impassive, with his big liquid brown eyes wide open and taking everything in. Sometimes he has headphones over his ears and on those days he looks particularly happy; some days he has a cigarette that he’s picked up somewhere or from someone. Doug never asks for money either but sometimes I give him a gold coin or even a five dollar note just because I like him. Once when he saw me leaving Liquorland with a bottle of wine he called out Give us a sip! but I didn’t because I wasn’t prepared to open a bottle in the street like that. I’d love to know who his people are and why he’s not with them but hesitate to ask. If he’s from Dubbo they’re probably Wiradjuri. He once told me he was inducted into the military, aged nineteen, and sent to Indonesia. You don’t see many people like him in a white bread suburb like Summer Hill.

Martin and Doug outside The Hungry Eye in Smith Street, Summer Hill. Photography by Maggie Hall.

In the days when I used to smoke I’d patronise the tobacconist’s shop up by the railway station. Jack is a Lebanese man in his sixties, perhaps, a devout Christian who has devotional messages scrawled on a whiteboard in his tiny office out the back praising the Lord. If you ask him how he’s going he is inclined to rhapsodise about the blessings daily poured down upon us; but he’s never insistent, never proselytises and has, on occasion, when I was trying to give up, refused to sell me cigarettes. I don’t know where he picked it up but he always calls me ‘Bro.’

The other place I used to go to buy smokes was the corner store, where Tim or Tom, I can never remember which, a sardonic Vietnamese man, sometimes wore a shirt that said: ‘I have the body of a god; unfortunately, the god is Buddha.’ Tom and his wife Tina, after 28 years, sold up the other day and moved to Cabramatta to start a restaurant there. They used open every day of the year except Christmas.

There’s another fellow called Tom who gets around most days in a ‘Pink Floyd’ T shirt, one that shows the cover of The Dark Side of the Moon. He has a pendulous lower lip that usually has a half-smoked cigarette attached to it, a large belly, shapeless trousers and a shambling walk; and spends his days, if he is not in the TAB, helping local shop-keepers with their daily tasks. For instance, he’ll be putting the plants on racks out the front of the florist’s in the morning, or taking them in at night. Or you’ll see him running a wheelie bin in or out for some café owner. These are routine tasks and I don’t know if he does them out of boredom, the goodness of his heart, or because there is some consideration attached. Tom the Pink Floyd Man is erratic: some days he greets me like an old friend, other days he shambles past as if he’s never seen me before in his life.

He lives somewhere over the other side of the park, perhaps at the same establishment as the Three Weird Sisters, grotesquely lumpy hairy-faced women who get around together, smoking cigarettes and occasionally drinking beers in the pub on the corner. I once ended up at their table, listening to some impressively vehement language as two of them disagreed as to the character, activities and whereabouts of a mutual acquaintance of theirs; while the third, who has a strange flat wide sunken yellow face, moaned softly and rocked back and forth in her chair. They’re probably not sisters and, appearances aside, not all that weird either. The argument over, the oldest of them, thin-lipped and grey-haired, bought me a glass of wine and murmured some endearment to me as they went on their way.

Most days a sinister cohort moves through the village, from the train station down the hill to the methadone clinic that operates out of a nursing home in a quiet suburban street one over from mine. I went there once, in a rage, after I came home from the library and found my neighbour, with her little girl, cowering in the face of two junkies who were—literally—shooting up in the dark passage that leads to the laundries under our building. The chemist, too, a Portuguese, used (legally) to dispense methadone from a clinic at the rear of his premises every Thursday morning but he doesn’t do that anymore.

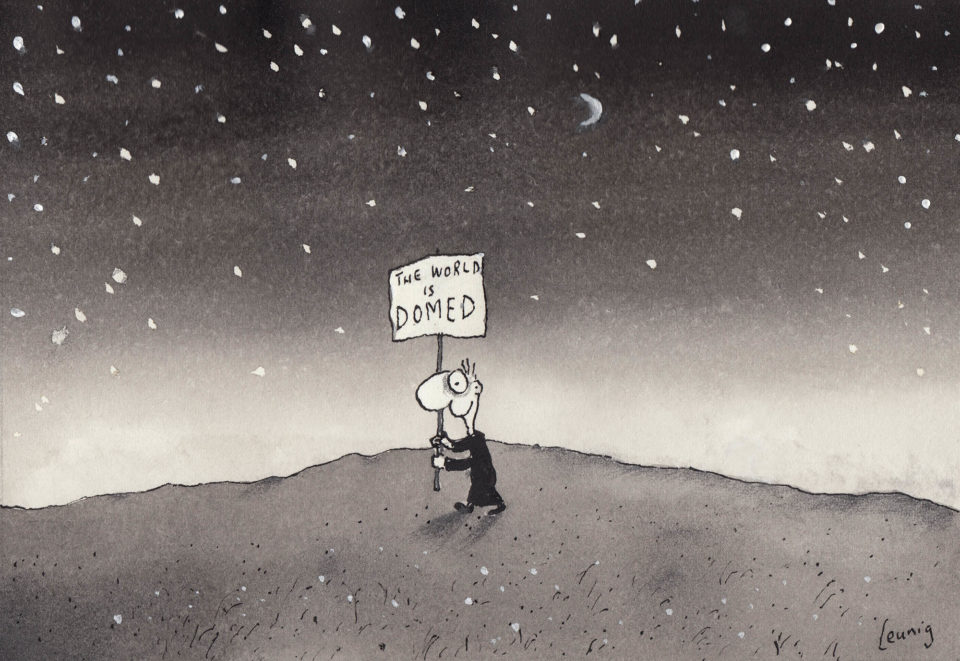

I don’t like junkies, don’t like the way they cringe and whine and steal; on the other hand, I’m an advocate of tolerance and would prefer that the rapid gentrification going on around here now did not exile all these colourful types from our streets; because, like the horse called Horse, they add a richness to the texture of living; and also, if I may be so bold, suggest there are other ways of being than approximating the moves you see rehearsed night and day in television advertisements.