Camperdown is not the kind of suburb that inspires allegiance. There are no commemorative plaques. No monuments to great men.

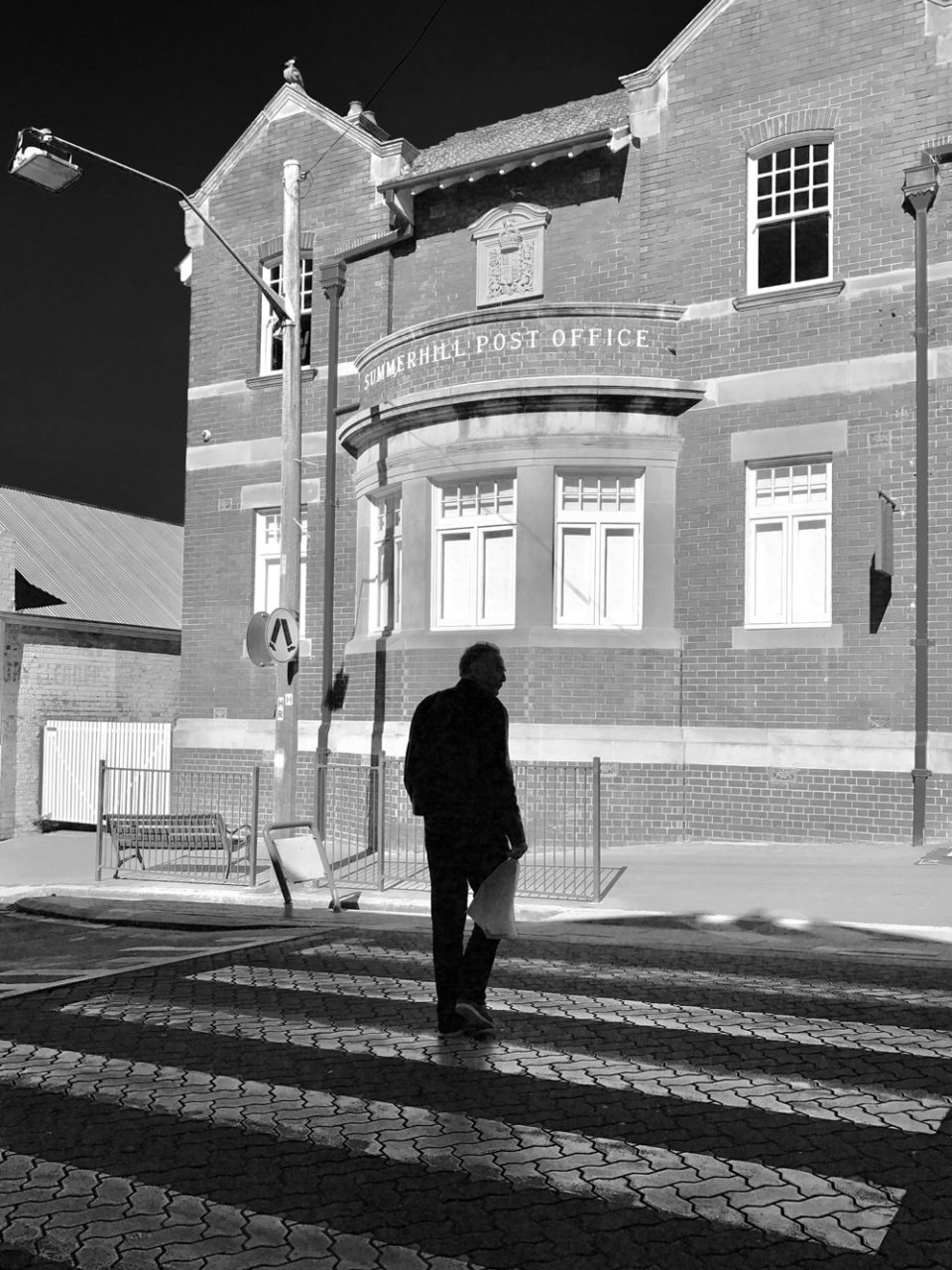

Kings Cross has its dark side and Glebe its churches, but Camperdown is different. It lacks an urban village, the row of useful shops that define a real suburb. The few large stores scattered along Parramatta Road: Ray’s Outdoors, Godfreys and Drummond Golf are located here because of the relentless stream of traffic that flows back and forth along Sydney’s oldest arterial road. Twenty years ago there was a Commonwealth Bank and a Post Office on the corner of Parramatta Road.

Traces of Camperdown’s working-class past linger between the newly converted warehouses and factories. One of the oldest industrial hamlets in Sydney, Camperdown at one time boasted a foundry, a soap and candle makers, a coach works, a cordial factory, a tannery, a glassworks, two biscuit factories, and a prosperous pottery works founded by Enoch Fowler in 1837.

At its peak Fowler’s pottery employed 70 men and boys. Robert Fowler, who inherited the business from his father, built a grand house at 14 Australia Street near Parramatta Road, a two-storied villa with its own ballroom and gardens, a fernery and an orchard. Today, overshadowed by a featureless block of modern units, the house survives in disrepair: overgrown with ferns and ivy, the name Cranbrook hand-painted in white on two sandstone columns.

Horses have played an important role in the suburb’s working-class past. A stone and concrete memorial stands in the shadows of the fig trees opposite Camperdown Park bearing the inscription: To Honour James Sullivan who lost his life on 23rd July 1924 when trying to save his employer’s Horses from death by fire.

We know little about this ‘Camperdown Hero’, as the Herald called him, other than that he lived locally and was an employee of Mr. W.E. Budd, who paid for his burial at Rookwood Cemetery. How many other stories of blue-collar workers deserving of recognition have been forgotten along this narrow corridor?

Camperdown is a slippery suburb to get a handle on. It is in a perpetual state of becoming.

In the laneway behind our house another factory is being transformed into boutique terraces. Gone is the art deco apartment that once graced the top floor of the 1930s factory warehouse and the Dairy Bell ice cream factory with its porthole upper windows.

Painted on the side of Building A of the University of Sydney’s Mallet St campus, Chesty Bonds, the patron saint of Camperdown, watches over us. This cartoon character is credited with selling 150 million athletic singlets.

It is impossible to be nostalgic about the suburb’s working-class past, or to romanticise the hotels, such as the Honest Irishman, now the Camperdown Hotel, stationed along Parramatta Road. The best of those old pubs, the Student Prince Hotel, is now a brothel serving the racing crowd.

A history of smells might reveal more about Camperdown than a history of facts, for the soap and candle works, the tannery, the foundry, the aerated cordial factory and the pottery works each produced their distinctive fumes and odours. The sweet marshmallow smell of chocolate-coated Wagon Wheels baking in their trays lingers in my memory long after the Westons Biscuit factory closed in Barr Street and was converted into modern spacious apartments.

Certain suburbs like Bondi or Paddington speak to us in the language of desire, of how we see ourselves, and how we want to be seen. So I wish I could say how much I’ve enjoyed living in Camperdown, but it is not a suburb that invites enthusiasm. On Victory Lane near Parramatta Road there is a scrawl of graffitti which reads Best to Forget. If Camperdown could speak it would say very little.

There are suburbs you don’t choose but somehow end up in, suburbs that you keep coming back to but never really belong in. It is only towards the park that I feel any attachment.

Aerial photos from the 1970s show Camperdown Park was similar to today while around it change has occurred at a relentless pace. The Greek corner shop is now Chinese-owned and the Chinese consulate behind razor wire occupies an entire block. The beauty parlour was once a betting shop, while the sports physio’s is an art gallery. The paint shop on the corner of Salisbury Road was once the local butcher’s. Needham’s garage on Australia Street, which for decades serviced Studebaker Larks and Hawks, is now an architect’s business and the trendy café on Fowler Street that was once a store is now called Store.

A memory of a place is merely a memory of the last time we remembered that place. Our memories, like the streets and homes around us, are constantly changing so that each time we visit a place we remember not what happened, but only our memory of what happened. Sydney Water is digging up cracked pipes near the park and I have a memory of them digging that same spot ten years ago.

Developers have demolished the Toyota dealership on the corner of Australia Street and Parramatta Road to build residential units but for a long while directions for its vehicles’ sales and service remained on its website. Traces of the past mingle with the present. Memories are laid down over memories until it is meaningless to unravel them.

A boy is bicycling towards Parramatta Road. Behind him in the distance are two horse-drawn carts and the blur of a third dray on the crest of the hill.

To his right is Camperdown Park surrounded by wrought-iron fencing, which will be removed during World War I. The park is gated and locked at nights in the manner of the public parks in London. Sandstone pillars mark the entry to the pedestrian paths.

These tall gracious pillars, one crowned with a stone angel, will also disappear. There are no automobiles on the road, only piles of steaming manure. In summer, dust from the dried horse dung on the street blows into front yards and open windows and breeds large numbers of flies; when it rains the liquefied manure and horse urine is carried into houses and shops on the boots of working men and boys. The sharp clatter of the horses’ iron shoes on the road creates a constant din, which combines with the curses of the drivers and the creaking hickory and steel wheels of the heavy carts and wagons overloaded with ice and milk and building materials. Sometimes a horse will slip on the paved road and break its leg or collapse from exhaustion in the street.

Dead horses are not an uncommon sight along Parramatta Road and their carcasses are soon dragged away. A single gas lamp stands on one side of the street and on the other side electricity poles have been installed, although there are no visible wires. Fowler’s pottery yard with its stacked terracotta drainpipes and chimney pots is separated from public view by a paling fence opposite the park and behind the open yard stands a row of eight identical terraces each with a narrow verandah.

The boy in the photograph is wearing a hat and coat. The street is scarred from the wheels of the heavy carts and dampness hangs in the air. Perhaps the boy works at Budd’s stables or at Fowler’s pottery? Or perhaps the boy is a messenger. The photograph is uncaptioned, yet the surroundings convey much about this old working-class Sydney suburb.

Silently the boy rides down Australia Street, bringing memories of the past.