I remember once, an afternoon I spent deleting dozens and dozens of photographs. Years’ worth of emails and text messages. I was trying to erase a void in time, a number of years, like you might stitch together a hole in a t-shirt. No one would see it, only I would know it was there, and then I could dedicate an enormous amount of energy to pretending that it wasn’t.

The photographs live on, however, sometimes in duplicate and triplicate, autosaved, on servers in Virginia and Oregon and Georgia, Iowa. All over the world. The cloud is nothing like a real cloud, it’s buildings: enormous, air-conditioned bunkers, guzzling energy. More than eight hundred images are uploaded to them each second, instantly multiplied, in practically endless copies of the people we used to be.

A website wants to remind me that it is a certain number of years since I moved to a town in the country. It wants to remind me of this even though I have opted out of the memory feature because I don’t want to be reminded. It reminds me of a time even longer ago when we were lost in a tropical jungle, a portend that I’d refused to heed. We were young, I tell myself, in an echo I think might somehow reach this past, and neither of us knew any better.

I try making block lists and deleting old images I’d missed and removing tags, but the algorithm still churns up these photographs, as in a haunting. In fact just the other day it showed me a photo of someone looking intimately at me across a dinner table, right down the barrel, and who I will never see again.

An unintelligent machine judges all of these things as equal:

Here is your mother, when she was still alive. Here is your toddler on the day they were born. Here is the kid from school who disappeared. Here are two people, together, from before they were married but not after they divorced. Here we all are, too young to be thinking of much beyond the next weekend.

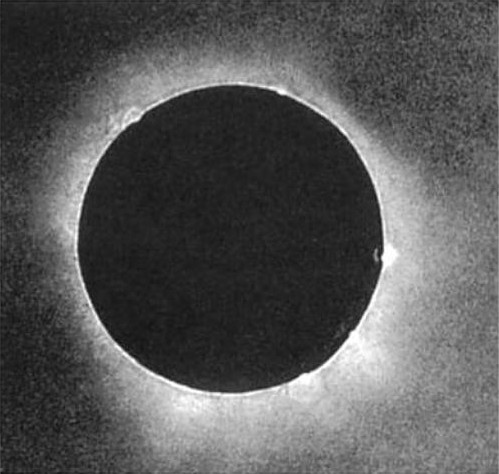

Not long ago there had been a total solar eclipse, which cast an enormous shadow over North America. The path of totality brought black darkness and hundreds of thousands of people to towns in the middle of nowhere. We could see it, partially, in Mexico, where the sun looked like a black, cartoon moon; a perfectly round segment missing from its top right quadrant.

Total eclipses are rare, not in how infrequently they occur here (somewhere on the planet every eighteen months), but in the cosmic sense. The moon is moving steadily, incrementally, away from the earth, and six-hundred million years from now, if anyone sentient is here, they will not be able to see a total eclipse any longer.

Lately I’ve started to play an old online word game again, on my phone. When I logged back in for the first time, all the years of abandoned games were still there. It was like a graveyard filled with people I no longer knew, their faces tiny squares. There is a message box in the corner that is mostly used for arguments and pedantry about the validity of this word or that. I saw a person there, a stranger now, whose wedding party I had been a member of. I remembered sitting at the table with their family. I thought for a moment of sending a message, but instead erased the game, collapsed the history.

Time stitched together again.

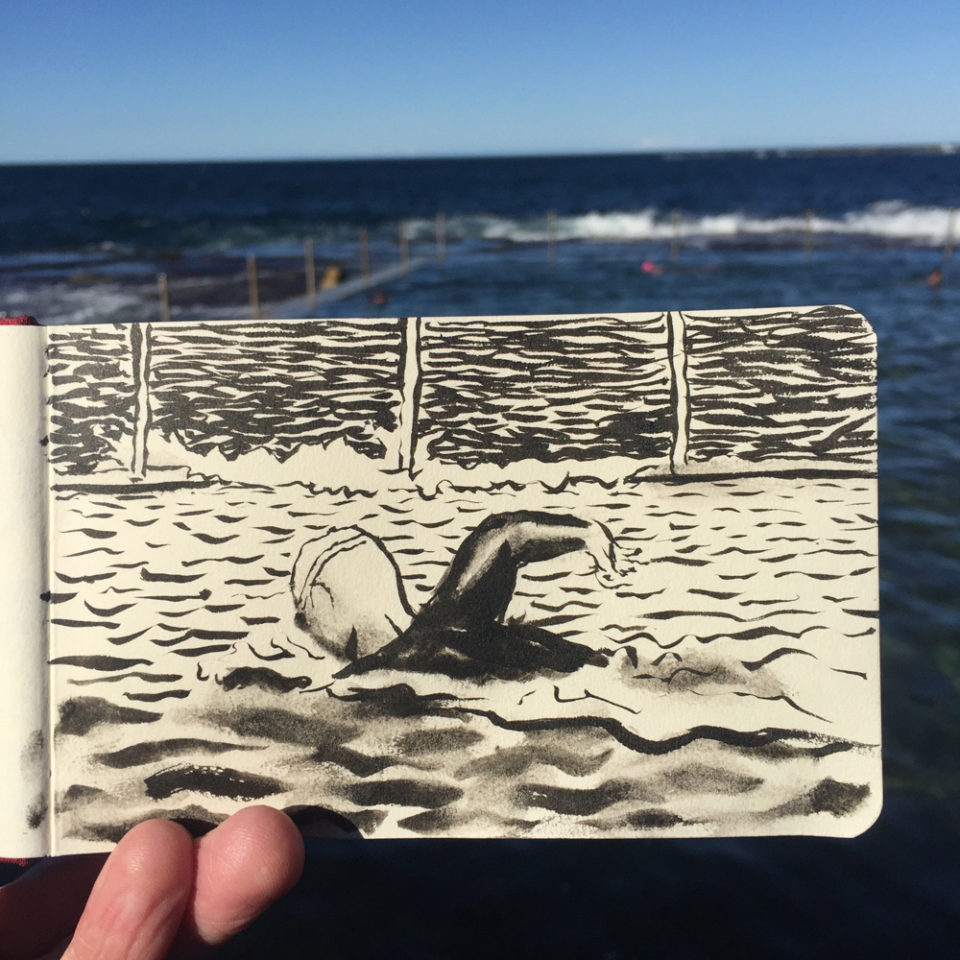

The morning before I left Australia I had been packing my bags. It was a hot day in Sydney in January and I’d had a plan to later swim at the beach. Buried in my satchel I’d found a set of keys to the old house in the country; when I’d left there I had never gone back.

In a roiling squall in the winter of 1912 the ocean churned and lifted a giant sandstone boulder from the sea floor up onto the rocks at one end of the beach, where it has stayed ever since. The naked rock weighs more than two-hundred tons. The beach is unchanged and impervious and perfect and vast and has remained the city’s jewel that it brags about clear across the continent.

I took the keys with me as I walked into the sea, dove under the breakers and swam out into the clear where I stood, wading, and, holding the keys over my head, hurled them as far as I could toward the horizon. They flew in an arc and instantly sank where they landed.

The waves that curled towards me looked like glass and we swimmers sank through them easily. The sun had started to set which cast that certain light, bright and fantastically clear, and I knew that this would be the place I would come to in my mind in all the months that would become years ahead, when I would never quite be sure where home was.

The first photograph of a total solar eclipse was taken in Russia in 1851, using a silver-coated copper plate. A copy is sitting on a corporation’s server somewhere now, so you can see it here:

Image: Julius Berkowski

Another photo, Your memories on this day 9 years ago. There you are in the one you took of us in the jungle. You, smiling, holding out the camera, me waving, tiny, in the background, the sun splintering down through the trees illuminating your head like a halo. I remember back then I had tried to look for the Blue Holes on the online map, to see if we were nearby. But the computer only returned blank white squares for the miles of ocean surrounding us, reading: This area is not yet mapped.

A perverse function of the cloud is that it will all, someday, be gone. Deleted or dead and unavailable in decades from now when the corporations who hold our memories no longer exist. When the power goes out and the infrastructure is gone. The internet is already disappearing; just try and find something there now from even only twenty years ago and you will have very great difficulty, if any luck at all.

You could print photos and try and preserve them, perhaps. The First Photograph dates from France in 1826 or 1827, no one is quite sure. It’s a view of a street in Burgundy taken from an upstairs window. You can see if here for as long as this web link is live, for as long as someone pays the server bill and the servers stay online powered by masses of electricity. Or if it is possible, you could travel to Austin, Texas and visit the Harry Ransom Center where the photograph hangs in the lobby.

In any case, you will be forgotten. Your own family will barely remember you in only three generations from now.

In that country town one day while we lived there they found the old streets buried right beneath the new ones. You could take a musty tour lead down by torchlight and see the old storefronts still perfectly standing. To get there you would take a trapdoor beneath a table in a hotel. Once below you could see that back then people had been shorter, and you had to stoop now to get through the doorways.

This is not uncommon, to pave something over anew once the old has outlived its usefulness. All over the world people are walking streets laid on top of the dead. Just east of the city of St Louis for example are the pre-Columbian ruins of Cahokia, buried directly below downtown. Its pyramid mounds predate colonial settlement by over a millennium. The town where I lived those few years, the old paved streets date back only around a century. The indigenous people who had called it home had been there for thousands of years.

There was a lake near our house, said to be named in the local Wathaurong language. It was a message to the colonists: “Wendaaree”. Please leave.

I had wanted to see the eclipse but truthfully I’d been afraid. I’d thought of catching buses to Tijuana, which would have taken a couple of days. But I knew that once I was standing in its path the shadow of the moon would come racing towards me at thousands of kilometres per second, which people had likened to being flattened by a truck. I knew from reading and rereading Total Eclipse that this could be an event of such catastrophic psychic reconfiguring that it was something I might not survive.

Here you are before, and here you are after.

The next day there were many photos, hundreds of thousands of them, uploaded to the internet. You could then see the eclipse without having seen it. But the eclipse chasers, the people who built their whole lives around crossing the planet to witness them wherever they happened, said that there was no photograph that could possibly be taken on earth, by anyone, that could adequately capture the terrible awe of a total eclipse.

My phone implores me constantly to update its software and continually I tap on its glass, Remind me later. Years have passed in this way. Eventually the time came where the phone was barely functional, so I connected it to my laptop as it told me to do, so it could perform the system upgrade. It connected itself to the internet and opened the photo application and there they were again, all the years of photographs I thought I had erased. Each neatly catalogued by time and place; houses and cities I no longer lived in. Towns and airports and countries I’d passed through. People I didn’t know anymore. Old versions of myself who I knew even less.

In the browser window you can collapse the images down into tiny rows of barely visible pixels or zoom in and blow them up to illegibly giant size. I highlight them all to delete them, the memories that are nothing but fungible and unreliable imaginings. An instant comes and passes, perhaps a tiny intimation of regret. An alert on the screen tells me, there is nothing to undo.